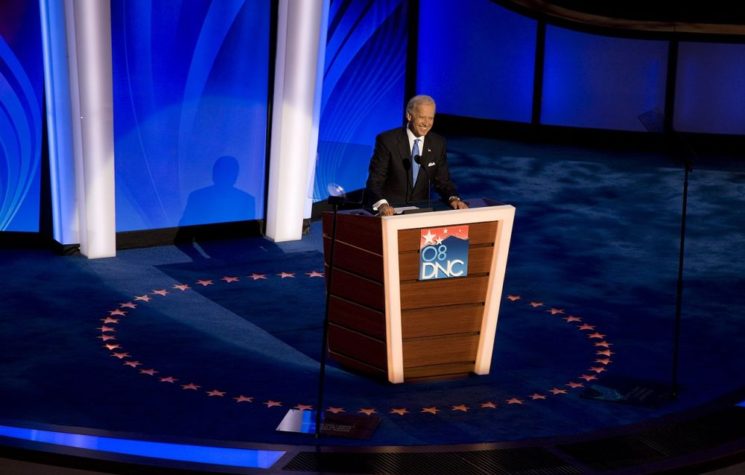

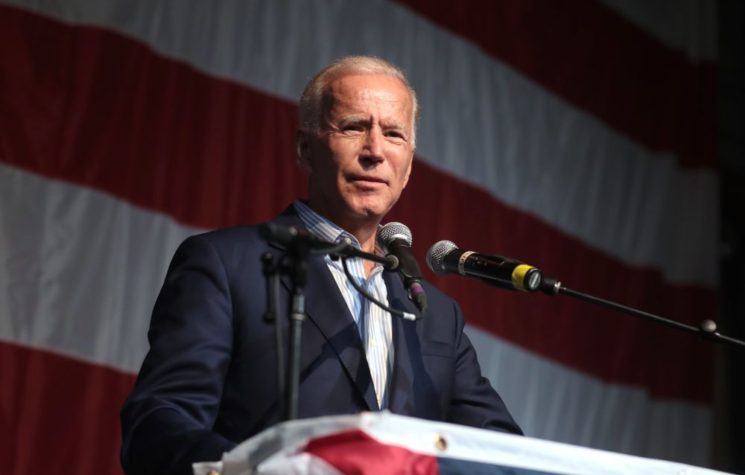

Now that mega-billionaire Bloomberg has realised the impossibility of being president of the United States, he has put his money behind Democrat and former vice-president Joe Biden who looks likely to be going to-to-toe with Trump for election in November. At first glance, he seems a reasonable enough candidate, as Bernie Sanders, who is now the only realistic Democrat alternative (and a longtime independent), is a self-described “democratic socialist” and the word socialist is anathema to an awful lot of American voters. Elizabeth Warren’s decision on 5 March to bow out was understandable, if regrettable, and now Biden’s the man to watch, and it is interesting to examine what his foreign policy might be.

There’s one major difference between Trump and Biden as regards the world outside America, and that is that Biden at least knows where various countries are on the world map, both physically and as regards their own foreign policies. The differences in their approach to US policy are significant, so far as can be made out from Trump’s past fulminations, and it seems that Biden is intransigent about several extremely important matters, including bilateral relations with Russia which he regards as “an adversary or even an enemy.”

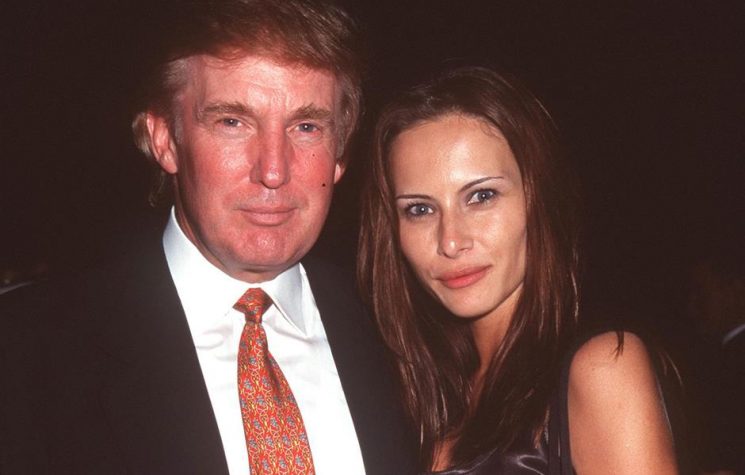

Trump’s foreign policy, such as it can be determined, is based on “America First” which is a weary slogan much favoured at populist rallies throughout the US, but derided by most of the world which, according to the most recent Pew Research survey is decidedly anti-American, while “a median of 64 percent of those surveyed said they don’t trust Trump to do the right thing in world affairs, and just 29 percent said they had confidence in the American leader.” He is “deeply disliked and mistrusted around the world.” Not very impressive after three years in the White House from where he has dabbled indiscriminately in the internal affairs of assorted nations that would have been much better off if he and his minions had simply left them alone.

Robert Blackwill, the Henry Kissinger senior fellow for US foreign policy at the Council on Foreign Relations, considers Trump’s foreign policy to be “better than it seems” but as befits an objective academic is drawn to observe that he “conveys foreign policy failures as successes and minor accomplishments as cosmic victories. He makes important decisions against the advice of his cabinet advisors — if he consults them at all. He has had unprecedented turnover in senior foreign and defence policy positions and, at this writing, has had three national security advisors. In sum, there is no steady interagency decision-making process within the administration because the president apparently does not believe that he needs one.”

No matter what a possible future president Biden may propose or project in the fields of foreign relations, it can be said that he will not regard his failures as successes, nor will he so cavalierly ignore the advisors whom he selects to help him navigate through the complicated waters of foreign affairs. On the other hand, thus far in his pronouncements he has displayed reluctance to consider dialogue as a tool of diplomacy.

He is forthright about Trump, as he well might be, and last December warned the American people that “If we give Donald Trump four more years, we’ll have a great deal of difficulty of ever being able to recover America’s standing in the world and our capacity to bring nations together. I think it’d be catastrophic to our national security and to our future. We can’t let it happen.” He is certainly right about Trump’s international standing, but there is as yet no compelling evidence that Biden will try to bring nations together. While he has indeed said he supports a two-state solution in the Israel-Palestine conflict, and has criticised the Trump’s absurd Middle East plan, saying “A peace plan requires two sides to come together” he has refused to endorse movement of the US Embassy back to Tel Aviv from Jerusalem where it is a symbol of Washington’s commitment to Zionism, which is defined as the “movement to establish a Jewish national centre or state in Palestine.”

While Biden is anxious not to commit himself about Palestine, he does declare that “When I am president, human rights will be at the core of US foreign policy” — although he is curiously silent about human rights abuses in some countries. China comes in for a pounding, of course, and he rightly observes that there is “very little social redeeming value in the present government in Saudi Arabia,” which is a most refreshing change from the fawning stance of Trump as regards that nauseating dictatorship. But Biden’s attitude to US-Russia relations is far from reassuring, and thus far he has adopted the stance of the Washington establishment which affects to believe that Moscow is engaged in a campaign to “subvert democracies in western Europe and the United States.”

It is never explained just what Russia would get out of subverting the existing forms of government in the West, but who needs explanations when conviction is so popular? The fact that Russia needs to trade with the West in order to improve the living standards of its citizens is ignored in spite of it being obvious that commercial and general economic cooperation cannot possibly be negotiated and effected with chaotic governments. There is simply no advantage to Russia in subverting the governments of the US and the UK for example — if only because the political leaders in both Washington and London are already making such a hash of attempting to run their counties that nobody would achieve anything but amusement by dabbling in their domestic affairs.

Mr Biden, however, subscribes to the dark theories of the Cold Warriors, and sees a lurking Moscow ever-ready to invade the West. The fact that according to the independent, objective Stockholm International Peace Research institute, the Russian defence budget stands at 61.6 billion while that of Western Europe totals 266 billion is apparently regarded by the Cold Warriors as evidence that Moscow in intent on going to war. America has forecast a mind-boggling expenditure of 705 billion for next year, and even the most dedicated Western believer that dark hordes of Russian warriors stand poised to roll through the Baltic States could not with assurance claim that such a scenario is credible.

Biden was asked “If Russia continues on its current course in Ukraine and other former Soviet states, should the United States regard it as an adversary, or even an enemy?” and answered “Yes.” It was not explained exactly what “its current course” was intended to imply, but Russia’s desire to continue mutually-beneficial bilateral trade arrangements with all these countries seems to be regarded as in some way threatening, which is as puzzling as the general anti-Russia campaign of disinformation and confrontation.

Biden is a supporter of the Nato military grouping, saying that “It’s an alliance of nations with shared values and interests” so it can be taken he is in favour of the 20 plus military exercises planned to take place along Russia’s borders this year, including “Defender-Europe 20 and six other linked exercises in April and May which will see the largest deployment of US-based forces to Europe for an exercise in more than 25 years.” Nato Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg declared on March 4 that the exercises will go ahead in spite of the Covid-19 epidemic which is sweeping the world, and it must be hoped that the US troops who are deploying to Europe from more than 20 states, including some with reported confirmed and presumptive coronavirus cases, will not spread the virus further.

But what is spreading further is the swell of anti-Russia sentiment, which seems set to continue if Joe Biden becomes president. Nobody knows what the course of US-Russia relations will be if Trump is re-elected, but at least there might be a chance of dialogue, even if the Washington Establishment is firmly opposed to rapprochement. All that Moscow can do is continue its discussions with European countries and concentrate on trade. That’s the route to peace and prosperity.