When considering the possibility of great-power conflict in the near future, it is difficult to bypass space as one of the main areas of strategic focus for the major powers. The United States, Russia and China all have cutting-edge programs for the militarization of space, though with a big difference.

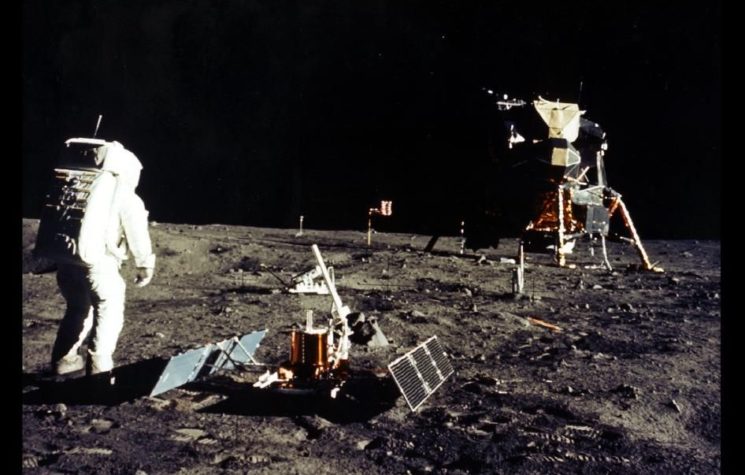

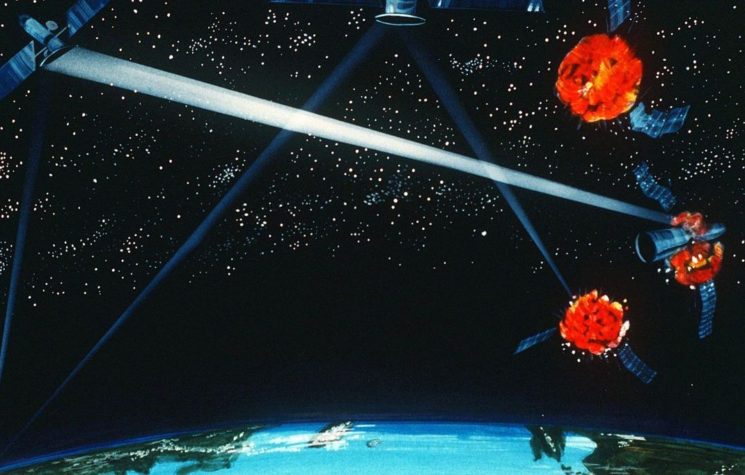

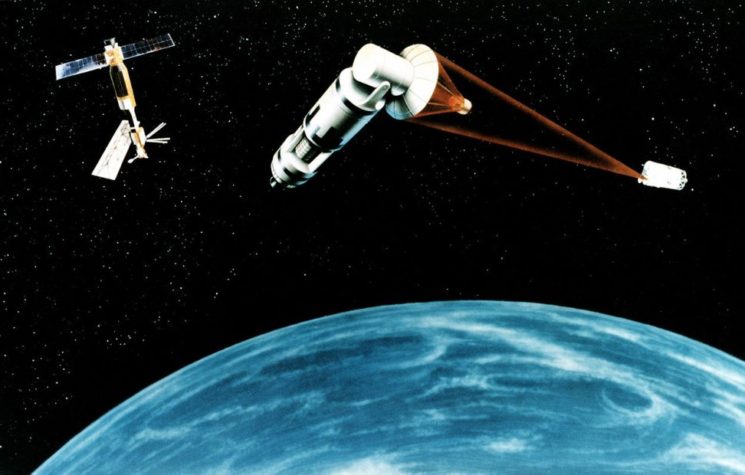

Donald Trump’s announcement of a “Space Force” is by no means a new idea. During the Reagan presidency, a similar idea was proposed in the form of the famous “Star Wars“ program, formally known as the Strategic Defense Initiative. It aimed to do away with the concept of mutually assured destruction (MAD) by positioning anti-ballistic-missile (ABM) interceptors in low-Earth orbit in order for them to be able to easily intercept ballistic missiles during their entry into orbit and before their re-entry phase. The costs and technology at the time proved prohibitive for the program, but military planners retained the dream of negating the concept of MAD in Washington’s favor, especially with the dawning of the unipolar era following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

The decisions taken in the years since, such as the US withdrawal from the ABM Treaty in 2002 during Bush’s presidency and from the INF Treaty during Trump’s, follows Reagan in trying to invalidate MAD, a balance of terror that has served to maintain a strategic stability.

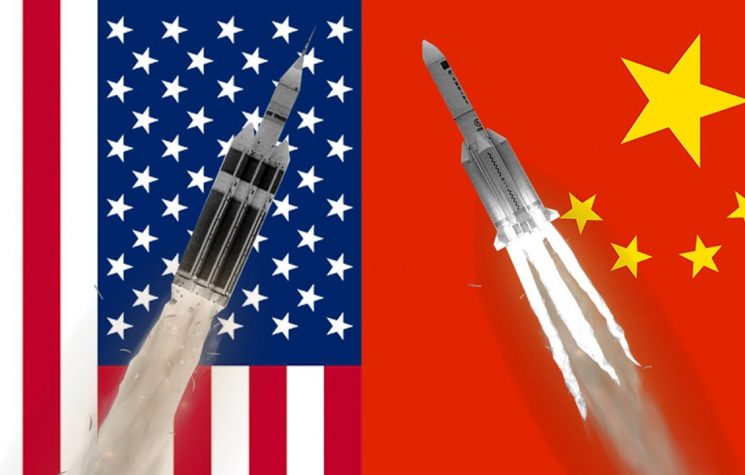

This hope of doing away with MAD so that the unthinkable may become thinkable has guided the missile developments of Russia and China, which through the development of hypersonic missiles aim to nullify the US’s ABM systems and thereby make the thought of an unreciprocated nuclear first strike MAD again. With Russia’s recent successes in testing hypersoning technologies, and the fast-tracking of other new strategic weapons announced by Putin less than 12 months ago, strategic stability seems to have been restored through Russia’s strengthened deterrence posture.

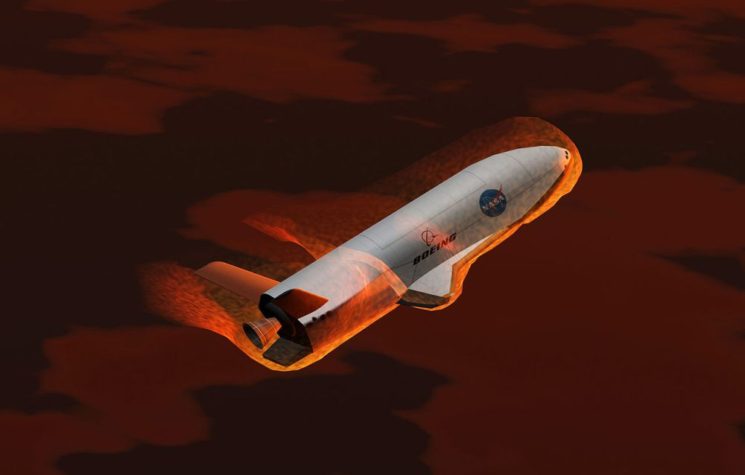

The weaponization of space is a less known and talked about aspect of Washington’s mad attempts to make mutually assured destruction no longer mutual and therefore thinkable. During the peak of the unipolar moment, the idea of the Pentagon and the lobbyists of the military-industrial complex was to develop the so-called Prompt Global Strike system, which envisioned being able to deliver an air strike with conventional weapons anywhere in the world in the space of an hour. The dream (or delusion) of the US was to have the unique ability to determine the course of events around the globe within an hour. Such experimental craft as the Orbital Test Vehicle seem to confirm that serious efforts have been underway to realize this objective.

Neither China nor Russia has been sitting idly by waiting to be struck undefended. Russia’s development of its S-500 system has been quite timely. The S-500 system is often considered an upgrade to the better-known S-400 system, but these are in reality different systems with different aims and objectives. The main task of the S-500 is to engage long-distance targets in low-Earth orbit. We are therefore talking about the ability to take out military or any future ABM satellites as those originally conceived with Reagan’s “Star Wars” program.

Unlike Washington, Moscow and Beijing do not appear to be developing space-based weaponry; they are certainly not going to increase their military budgets to create a space force. On the contrary, both countries have been working for more than a decade on a proposed Prevention of an Arms Race in Outer Space (PAROS) treaty that seeks to ban the weaponization of space. The aims are summarized as follows:

“Under the draft treaty submitted to the [Conference on Disarmament] by Russia in 2008, State Parties would have to refrain from carrying out such weapons and threatening to use objects in outer space. State Parties would also agree to practice agreed confidence-building measures.

A PAROS treaty would complement and reaffirm the importance of the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, which aims to preserve space for peaceful uses by prohibiting the use of space weapons, and technology related to ‘missile defense’. The treaty would prevent any nation from gaining a military advantage in outer space.”

The intentions of the draft treaty clearly go against Washington’s plans. It is therefore not surprising that Washington has no intention of acceding to PAROS, and it is probably only a matter of time before Washington withdraws from the 1967 Outer Space Treaty.

Trump is looking at things from a practical point of view. He wants to give a major boost to the military-industrial complex, which is salivating at the prospect of being showered with tens or even hundreds of billions of US taxpayer dollars in a quest to weaponize space. But the policy makers in Washington and in think-tanks look at the weaponization of space from a different perspective. They look at it from the point of view of Washington as a superpower that must seek to prolong its unipolar moment through the use of force, even from space. While it is delusional nonsense, it has nevertheless been the prevailing outlook in Washington for at least the last 25 years.

The reason why China and Russia have proposed and continue to discuss the PAROS lies in their political and military philosophies that contrast with that of the US. As an imperial power bent on global domination, the US is always looking for ways to subjugate and dominate what it considers to be its underlings, while Russia and China act to hold back and counterbalance US aggression, in the process serving to enhance global stability.

The proposal for the non-militarization of space is the latest example of what unites and guides the Eurasian strategy of China and Russia without having any illusions about Washington’s intentions. The development of the SR-72 system seems to confirm that Washington wants to also bridge the gap with its Eurasian competitors in the field of hypersonic technology in addition to wishing to weaponize space.

Realistically, however, global powers in a multipolar context will seek to defend their territorial and economic sovereignty with every means at their disposal. Likewise, those seeking global hegemony will try to exploit any existing domain to gain an advantage over their rivals.

China and Russia seek to weaponize distance and speed to make any possible US attack on them impracticable, both in terms of the logistics required and the revivified cost-benefit calculus of MAD. The US, on the other hand, is trying to weaponize all conceivable domains of conflict by all means possible, hoping to be able to find a chink in its opponents’ armor.

Beijing and Moscow seem to have studied extensively how to respond. All the various defensive systems produced in recent years, from hypersonic anti-ship missiles to multi-layered defense systems like the S-400, S-500 and A-135/A-235, seem to meet the challenge.

Beijing fears US naval strength, and while seeking to achieve parity and surpass the US in the future, it aims above all to prevent the use of aircraft carriers as launching platforms through the employment of defensive area-denial weapons. In this sense, speed (Mach 10) and extending the range of Chinese anti-ship missiles (DF-21) are fundamental to the success of this strategy. Similarly, Moscow intends to seal Eurasia’s skies, and the S-500 seems to be the final flourish, able to protect up to 800 kilometers above sea level.

The weaponization of space is the latest issue that the US is exploiting for various political purposes. Be that as it may, this creates an adversarial environment that compels the US’s peer competitors to develop weapons capable of countering US belligerency. Instead of sitting down and defining the parameters of major-power interaction so as to reduce the likelihood of war, we are witnessing an intentional US policy of pursuing an arms race in every possible domain of warfare.