Alisa ALEKSANDROVA – Independent analyst and researcher

In his book Ukraine at the Crossroads (2015), former Ukrainian Prime Minister Nikolai Azarov writes: «Essentially, Ukraine has never been a mono-national state. The Donetsk and Luhansk regions were different from the Kharkiv region, and the Zaporizhia and Dnepropetrovsk regions were different from the Sumy and Chernigov regions. And I am not even going to talk about Galicia and Transcarpathia. Ukraine as a unitary state is a constant source of conflict».

The fact that the unitary state structure of Ukraine has started to create a permanent civil conflict is confirmed by recent events. Yet the Ukrainian authorities are still obstinately insisting that «Ukraine was, is, and will be a unitary state».

If we divert our attention away from the situation in the DPR and LPR, the dogma of a «unitary Ukraine» is most in conflict with reality in Transcarpathia. This is now the third decade that the results of the 1991 Ukrainian referendum, in which 78 per cent of the population of Transcarpathia voted in favour of creating a self-governing territory within Ukraine, have been ignored.

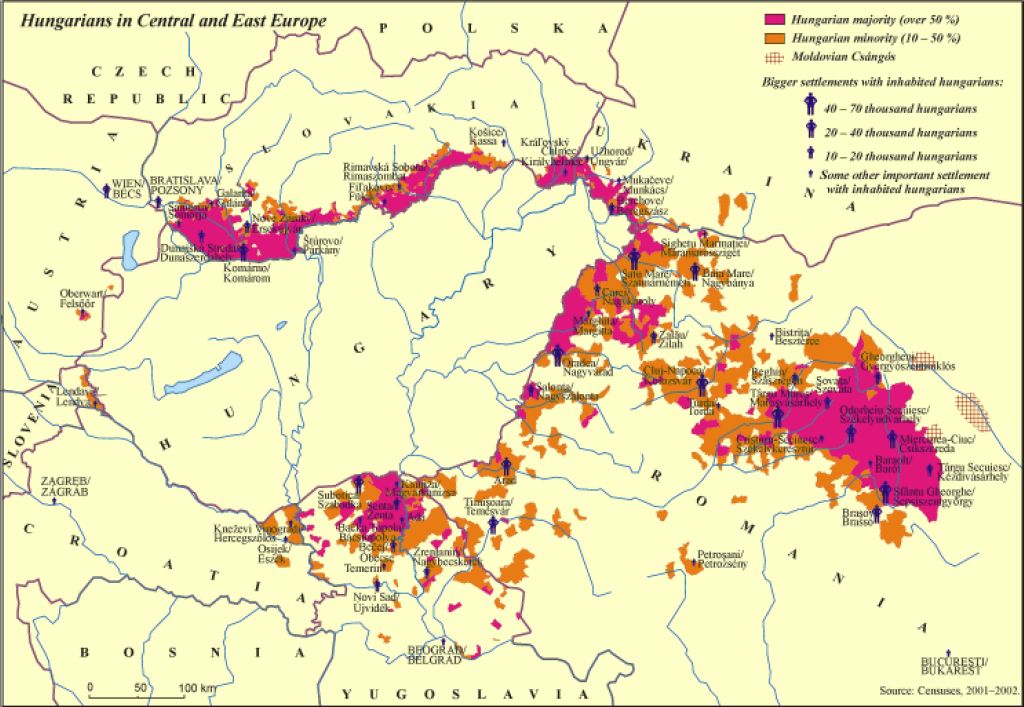

The situation in Transcarpathia is being watched particularly closely by neighbouring Hungary. The estimated number of Transcarpathian Hungarians ranges from 150,000 to 200,000 people, and nearly 100,000 of these have Hungarian citizenship. Yet that is not even the most important thing. The most important thing is that Hungary does not see Transcarpathia as a faceless part of a «unitary Ukraine» (Petro Poroshenko’s words), but as territory that is, in many respects, not that foreign. As far back as the beginning of the 11th century, during the time of the medieval Hungarian kingdom of Saint Stephen, Transcarpathia was part of the Hungarian state. Later, the territory was, for a long time, under the rule of the Austro-Hungarian Habsburgs. It was only the events of the two world wars and the post-war peace settlement that put an end to the centuries-old presence of Transcarpathian Hungarians within Hungary.

It is no exaggeration when people say that there is now a threat hanging over the Hungarians of Transcarpathia. The mobilisation announced by the Ukrainian authorities could, at some point, exhaust the patience of Hungarians on both sides of the border. The leading Budapest newspaper Népszabadság has reported on the dramatic fate of the 128th Brigade of the Ukrainian Army, whose ranks include Transcarpathian Hungarians. According to a statement made in Uzhhorod by the brigade’s commander, Evgeny Pilguy, the brigade has lost more than 100 soldiers since the start of military operations in Eastern Ukraine. Fifty-eight of these were killed in this year alone, mainly in the area of the ‘Debaltseve Kettle’.

Another Budapest newspaper, Népszava, has also written about the threat of mobilisation. This refers to Kiev’s plans to subject those residents of Transcarpathia who are intending to leave the region, including with the use of documents from neighbouring Hungary, to serious liability. Budapest claims that tens of thousands of people (by the most conservative estimate) have already successfully left Ukraine or are intending to do so. The Ukrainian authorities are particularly outraged at those residents of Transcarpathia who are helping their fellow countrymen avoid receiving mobilisation orders or are hiding the fact that they have a passport from another country.

All this is being perceived by Hungary as persecution on ethnic grounds and is not going unanswered. In early February 2015, the National Security Committee of the Hungarian Parliament discussed the situation regarding the Hungarian minority in Ukraine. Deputies noted that Transcarpathian Hungarians were being called up to join the Ukrainian army «disproportionately to their numbers», so in excessive amounts, in other words. The committee’s deputy chairperson Bernadett Szél, from the Politics Can Be Different party, stated: «The situation is grave, and Hungary must ensure the protection of its fellow countrymen in Ukraine». The chairman of the committee, socialist Zsolt Molnár, has called for the government «to take steps so that Ukraine cannot mobilise more Hungarians than is justified by the size of their community», while Ádám Mírkóczki, a member of Jobbik («The Movement For a Better Hungary»), one of the leading parties, has openly stated that the Hungarian government «should stop worrying about the territorial integrity of Ukraine».

The accession of Transcarpathian Hungarians began a year ago, when nearly 40 Hungarian organisations in Transcarpathia appealed to the Ukrainian Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk to provide them with «equal rights and protection». At the same time, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban stressed that the Hungarian community in Ukraine «must be given dual citizenship, collective rights and autonomy». «These are our clear expectations of the new Ukrainian authorities,» Orban declared.

At the same time as the Transcarpathian Hungarians became more active, so did the Rusyns, who have never considered themselves Ukrainian despite all the excesses of Ukrainisation. In 2006, the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination recommended that Ukraine recognise the Rusyn nationality, but Kiev ignored this recommendation.

More than 10,000 residents of Transcarpathia have now signed an appeal to the Ukrainian president and the Verkhovna Rada asking for the results of the 1991 referendum to be put into action. The collection of signatures is still going on. The Rusyns are calling for their language to be recognised, for it to be taught in schools, for a Rusyn language department to be opened at the Uzhhorod National University, and for the creation of Rusyn-language programmes on local television and radio. The next session of the Coordination Council of Rusyn Organisations is scheduled to take place on 8-10 April. Its organisers are working closely with Hungarian activists and members of other national minorities in Transcarpathia. The «unitary Ukraine» will not be able to disregard the issue for much longer.