To what extent would US maritime forces be willing to get involved?

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

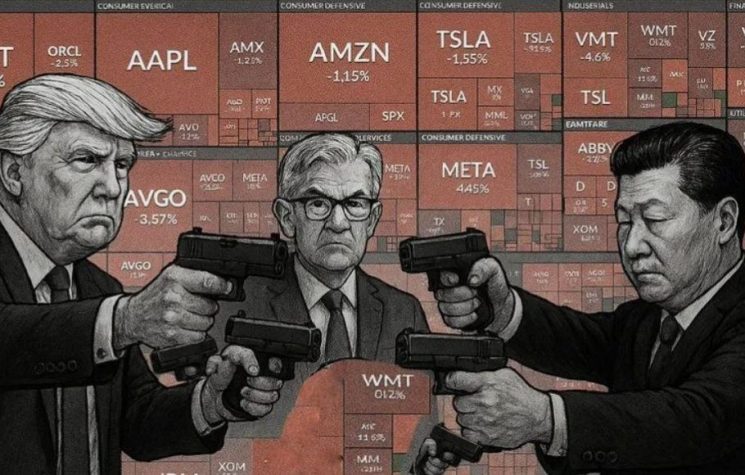

In the map war, the United States of America has identified China as its primary enemy, surpassing its traditional rivalry with Russia.

The first type of approach that deserves attention, employed by the US to counter Chinese operations in the “gray zone,” concerns so-called presence operations, i.e., activities in which the US armed forces, alone or together with allies and partners, legitimately exercise their presence in areas—such as the South China Sea—where China attempts to oppose them through its range of hybrid strategies. In this context, two main ways of strengthening presence emerge: Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPs) and the concept of maritime counterinsurgency (maritime COIN). A third approach, based on joint and multilateral exercises, is examined in Chapter 5, which focuses on supporting allies and partners against Beijing’s actions in the gray zone.

Freedom of navigation operations and overflights

The United States conducts FONOPs as part of the FON program, designed to assert the right to navigation and overflight in all areas of the globe.

Established in 1979, this program combines “diplomatic and operational” tools to safeguard legitimate trade and ensure the global mobility of US forces, including in the South China Sea region. Although not in itself a specific strategy against hybrid warfare, numerous analysts and interviewees emphasize that the FON program is crucial to countering Beijing’s expansionist vision, which claims excessive maritime rights over large portions of the South China Sea.

Technically, the Americans compare freedom of navigation to the ‘right of way’ in English common law: it exists as long as it is exercised, but if it falls into disuse, it eventually lapses, with the result that ownership reverts fully to the landowner.

The United States, therefore, publishes an annual report listing countries accused of making excessive maritime claims and against which the US Navy has carried out challenge passages. However, it does not indicate how many times these operations are conducted in each sea. In 2022, the last year for which public data is available, Washington challenged 22 excessive maritime claims from 15 different states. However, a report by the Congressional Research Service, obtained through the Freedom of Information Act, revealed that between 2017 and 2020, the US Navy carried out 54 FONOPs against Chinese claims in the South China Sea and the Taiwan Strait, with a steady increase over the period considered. Curious, isn’t it?

As a rule, the United States does not publicly announce every single FONOP, and most take place without press releases or media coverage, but in some cases, operations are made public, often as a direct response to Chinese protests. One example is the March 2023 operation of the destroyer USS Milius near the Paracel Islands, which was made public after Beijing claimed to have repelled the American vessel. A media tit-for-tat. These communications serve to refute false Chinese claims that the PLA Navy has ‘driven away’ US ships.

Alongside FONOPs, Washington also conducts aerial overflights of the South China Sea, which are not always publicly announced. While it is true that reconnaissance plays a crucial role in mapping conflict territories (even if only potential), it is equally true that the US is a master of provocation.

Maritime counterinsurgency

In addition to transit passages, the United States has responded in at least one emblematic case with a prolonged naval presence to defend a Southeast Asian partner under Chinese pressure.

The episode known as the “West Capella incident” occurred between late 2019 and early 2020, when Chinese Coast Guard and maritime militia vessels obstructed the drilling ship West Capella, employed by Malaysia in its EEZ. In response, in April 2020, Washington sent the amphibious assault ship USS America and two escort units, followed by two littoral combat ships that patrolled the area for several weeks.

This presence was accompanied by public statements of support for Malaysia’s right to exploit its energy resources, expressed by senior commanders of the Pacific Fleet and the 7th Fleet. In the end, the Chinese units withdrew and Malaysia was able to continue its explorations undisturbed, an event hailed as an operational and communicative success.

That speech was an extraordinary prototype, useful in inaugurating a new mode of support for regional partners against what American strategists call “Beijing’s coercive maritime insurgency.” The episode also had knock-on effects, encouraging Indonesian naval maneuvers, the Philippines’ decision to enforce the 2016 arbitration, and a Malaysian protest at the United Nations.

The concept of maritime counterinsurgency draws inspiration from strategic reflections, such as those of Hunter Stires, who compared China’s actions to a true maritime insurgency: a political contest for regulatory control and authority in regional waters. According to this view, traditional FONOPs would be comparable to “search and destroy” operations in Vietnam, incapable of establishing lasting control. On the contrary, a strategy of persistent presence, similar to the Combined Action Program of the Vietnam War, would allow for the constant protection of civilian mariners, giving them confidence and security in asserting their rights.

Since then, various studies and articles—including those authored by high-ranking US Navy officers—have reiterated the importance of a maritime counterinsurgency strategy or, in more recent terms, an enhanced maritime presence. After the West Capella incident, Washington continued to provide limited direct support to civilian and naval units of regional partners. With the Philippine Navy, for example, the United States conducted joint patrols that helped reduce the frequency of Chinese intimidation, creating a control mechanism for Manila in disputed areas.

The continuation of the American strategy

Many experts—though not all—consider FONOPs and air overflights to be fundamental tools for countering Chinese operations in the gray zone, but these initiatives alone are not enough. In fact, FONOPs merely reaffirm the right of passage of foreign military units. This is a necessary but insufficient step: in the American logic, the ‘benefits’ for Southeast Asian states, which have China as a maritime partner, remain limited. The US administration has reiterated the ‘America First’ principle, but has often left behind its partners and allies in the South China Sea.

Some possible ways to strengthen the geopolitical impact of FONOPs would be to increase their frequency and give them greater public visibility. According to several USINDOPACOM officers, an increase in the pace of operations could be useful, although it is not easy to determine what the optimal number would be. Another possibility is more systematic communication: press releases, dissemination of videos, or even the presence of media on board. If one of the functions of FONOPs is to demonstrate that China’s claims are excessive and illegal, then publicizing them would amplify the message.

Despite the success of Operation West Capella and the subsequent focus on the maritime COIN model, the United States has not directly replicated that type of intervention in other gray zone crises. The concept has been discussed in exercises and simulations at the Pentagon, and Congress has reiterated the need to defend what they call “freedom of navigation” and counter Chinese activities. However, it is true that the reluctance to embrace a COIN approach also depends on Washington’s current strategic orientation: after the failures in Afghanistan and Iraq, and before that in Vietnam, the world of national security is now focused on competition between great powers, moving away from the COIN paradigm typical of the post-9/11 era.

It is therefore not surprising that part of the armed forces and the Department of Defense (now the Department of War) do not favor the adoption of a counterinsurgency approach in the Pacific, which would seem of little use in preparing for a possible direct conflict with China in the scenario so dear to Americans, namely Taiwan. Hence, the four operational lines of the Seize the Initiative model, designed to enable the US military to operate rapidly within the first island chain with reconnaissance, attack, and interdiction capabilities. While including countering hybrid operations, the priority remains preparation for high-intensity conflict.

China, however, is pursuing a dual-track strategy (or perhaps even more than two): on the one hand, it is preparing for conventional conflict, while on the other, it is seeking to ‘win without fighting’ in the present. The United States and its allies cannot choose which threat to address: they must counter both, or risk defeat. Preparing only for conventional warfare will not be of much use if the hybrid threat is not stopped.

Added to this are further obstacles: the political will of the countries in the region, their minimal capacity to participate in such an effort, and the perception that cooperation with Washington is truly useful. Then there is the risk of escalation: the close proximity of US units alongside Philippine, Malaysian, or Vietnamese ships could lead to incidents with Chinese forces. So, to what extent would US maritime forces be willing to get involved?