At a time when the world is in turmoil, oscillating between peace negotiations and threats of war, there is one issue that needs to be addressed with care: the concept of neutrality.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

A preliminary definition

At a time when the world is in turmoil, oscillating between peace negotiations and threats of war, there is one issue that needs to be addressed with care: the concept of neutrality.

Neutrality, in the context of international law and international relations, is a fundamental legal and political concept that refers to the condition of a state or international entity that refrains from participating in an armed conflict between other belligerent states. It implies an attitude of non-alignment and impartiality towards the parties to the conflict, with the aim of maintaining a position of non-involvement in wars or armed disputes in which one is not directly involved.

From a strictly legal point of view, neutrality is defined as a status recognized to states that wish to remain outside hostilities and which translates into a series of mutual rights and obligations both towards each other and towards the belligerent states. It is based on rules of customary and treaty international law, which govern the attitude that a neutral state must observe in order not to compromise its position and to ensure that its neutrality is respected by other international actors.

Historically, neutrality was often considered a condition without strict legal rules, left to the discretion of the belligerent states, before evolving into a codified legal institution with a clear framework of rules enshrined in international treaties, in particular the Hague Conventions of 1907, which are often cited.

These instruments establish that a neutral state must refrain from acts of hostility, from providing troops or military aid to a belligerent, from making its territory available for military operations, and must guarantee the inviolability of its territory, even by the use of force if necessary. Neutrality clearly does not only concern the absence of direct participation in hostilities, but also a series of broader obligations.

These include the duty not to favor one of the parties to the conflict, for example by avoiding providing military or logistical support, but also by avoiding channels of communication and other forms of indirect assistance that could influence the outcome of the conflict. Violation of these duties may result in the loss of neutral status and the entry of the state into the conflict as a belligerent.

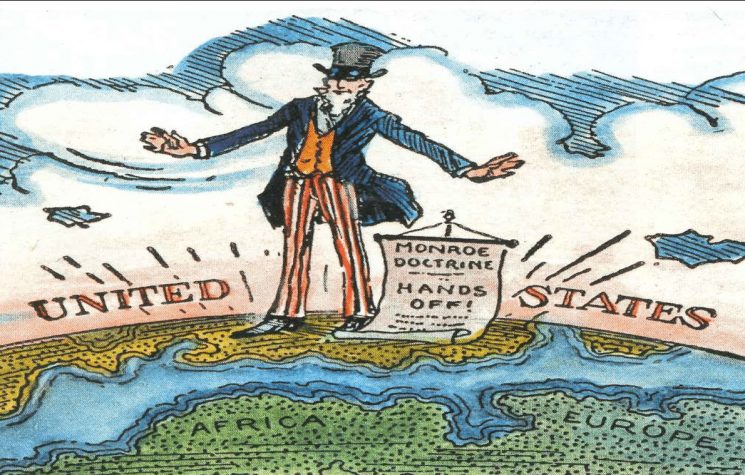

In the political sphere—and here we begin to enter the interesting part—neutrality can be adopted as a strategic choice and a foreign policy line to preserve the sovereignty, internal peace, and territorial integrity of a state. Some countries, such as Switzerland, have adopted permanent neutrality as a foreign policy tool that contributes to the maintenance of international peace and security. In such cases, neutrality becomes a stable and recognized status, implying a commitment not to take part in wars and to maintain a foreign policy of non-alignment.

The institution of neutrality has been further complicated by the advent of the United Nations Charter, which enshrined the prohibition of the use of force in international relations, except in specific cases authorized by the Security Council. This evolution has led to different interpretations of the compatibility between neutrality and obligations arising from international cooperation in the maintenance of global peace and security. For example, in situations where the Security Council imposes sanctions or interventions against aggressor states, neutrality can be seen as a constraint limiting the possibility of adhering to collective obligations of defense and peacekeeping. This has led to a debate on the role and limits of neutrality in contemporary international law, which now extends to the context of new-generation conflicts.

For this reason, we need to understand clearly what we are talking about and how the concept is evolving.

Things don’t always work as planned

Let’s look at it from a military strategy perspective. Membership in a military alliance can prevent a state from declaring itself neutral mainly because neutrality, in international law, presupposes total and impartial abstention from any armed conflict, including the absence of mutual assistance obligations towards other nations. Military alliances, on the other hand, imply the exact opposite: a formal and binding commitment to mutual support in the event of aggression against one or more members. ‘Formal’ and ‘binding’ are two key words that are legally valid.

More specifically, the elements that explain why membership of an alliance precludes neutrality are:

- Mutual assistance obligation: many military alliances, such as NATO, include clauses requiring members to defend each other in the event of an armed attack (e.g., Article 5 of the NATO Treaty). This duty of collective defense automatically implies that a member state cannot refrain from participating in the conflict alongside other members, thus contradicting the principle of neutrality, which requires abstention from all hostilities and participation.

- Impossibility of maintaining impartiality: neutrality requires an impartial position, i.e., not favoring or supporting any of the parties to the conflict. Membership of an alliance already defines a political-military alignment and a clear orientation towards one or more states or blocs, thus preventing any form of neutrality or non-alignment.

- Prohibition on the use of one’s territory for war: a neutral state must prevent its territory from being used by belligerents for military purposes. Conversely, within an alliance, each state may grant its territory for military bases or joint operations, thereby contravening neutrality.

- Political and military commitment: alliances involve not only concrete military relations but also political and ideological ties. Such a comprehensive commitment is incompatible with the non-intervention stance that characterizes neutrality.

- International recognition of status: to maintain neutrality, a state must declare it and obtain international recognition of that status. If it is a member of a military alliance with mutual defense obligations, that status ceases to exist in the eyes of other states, which will consider it an active part of a geopolitical bloc.

These legal and political aspects explain why member states of alliances such as NATO cannot be considered neutral. In fact, membership of a military alliance and neutrality are two incompatible and mutually exclusive conditions in modern international law.

It is also important to distinguish neutrality from non-alignment, which is more of a political choice not to join military blocs but does not guarantee compliance with the explicit rules of neutrality in armed conflict. Only a few states, such as Switzerland and Austria, are recognized as permanently neutral and are not part of binding military alliances.

Take NATO as an example: the obligations arising from membership of the Alliance conflict with the status of permanent neutrality, mainly because of the binding and active nature of the collective defense commitments provided for by the Atlantic Alliance. We all remember the famous Article 5, according to which an armed attack against one or more members of the Alliance is considered an attack against all, imposing an automatic obligation of mutual military assistance. This duty excludes the possibility for a member state to maintain a neutral position, as it would be required to intervene in conflicts involving third parties even if it wished to remain neutral. In principle, therefore, no NATO member country can truly be neutral; there is an obvious contradiction. Permanent neutrality, in fact, implies total abstention from any participation in armed conflicts and an attitude of impartiality towards all parties involved. Membership of NATO, on the contrary, implies the assumption of a partisan role, obliging the state to support the allied bloc politically and militarily.

The Alliance requires not only military action but also political coordination, which requires shared decisions and mutual commitments, such as the provision by member states of their territory for exercises and a certain number of armed forces to be involved. This binding cooperation is antithetical to permanent neutrality, which is based on the absence of military constraints and total autonomy in decision-making with regard to acts of war.

Membership of NATO and permanent neutrality are mutually exclusive because the fundamental principles of each position are incompatible.

The hybrid context

It is therefore clear that we must ask ourselves questions about how this neutrality works today, when we have new types of conflicts, hybrid conflicts, and new modes of operation.

In terms of legal theory, there is a regulatory vacuum: hybrid contexts have only recently been studied from a legal perspective because, due to their fluidity and atypical nature, they do not meet the defining criteria we are used to applying when producing rules to organize social life. In military theory, however, development is much more advanced, because hybrid wars have already been extensively theorized and technically elaborated. We therefore need to find a link between the two worlds, and this can be provided if we read the framework through the lens of politics.

Let’s take an example to better understand this: Finland. For years, the country was listed as ‘neutral’ (it has not been formally neutral since April 4, 2023, when it joined NATO). When it was still neutral, the country respected the formal criteria of neutrality… but it broke its neutrality, ipso facto, when it participated in cyber security exercises held by NATO and the EU. Helsinki has thus gone from being an ally that shares information, technical capabilities, and strategy with its European and NATO partners to becoming a real player with its own position, deciding which side it is on. After years of “Finlandization,” i.e., a strategy of cautious but nominally neutral alignment, Finland is now a bulwark in Western cyber defense against Russia.

Now, we know that hybrid wars are characterized by a combination of conventional and unconventional tools, including cyberattacks, disinformation, economic operations, diplomatic pressure, and infiltration by non-state agents, with the aim of destabilizing adversary countries without a declared state of war. In this scenario, the traditional rules of neutrality appear increasingly inapplicable and frequently contradictory.

Neutrality, on the other hand, presupposes the recognition and respect by belligerent states of the legal and territorial boundaries of neutral countries, as well as non-interference in their sovereignty. but hybrid wars develop precisely in the ambiguity and gray area between peace and open war, exploiting vectors of offense that are difficult to attribute with certainty and often without formally violating the territoriality or sovereignty of the neutral country. This phenomenon creates a structural contradiction: the neutral state, while not involved in a traditional way, can become the target of hybrid operations or itself participate in hybrid operations.

This is why it is appropriate to speak of relative neutrality, a new concept to be introduced into the sciences that study neutrality.

Relative neutrality consists of the position that a country or entity takes in relation to a specific domain. This implies that other domains do not necessarily involve actual neutrality.

Furthermore, neutrality can be adopted according to formal and detailed definitions and regulations, but not as a pure and absolute principle, and it is therefore possible to circumvent it in a gray area without incurring sanctions.

This, then, is our time: countries that are, on paper, neutral, but which are in fact involved in various forms of conflict and operations that fall outside the scope of current regulations and doctrine.