By Natylie BALDWIN

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

Natalyie Baldwin asks the British author about the Soviet collapse, the 1990s, Vladimir Putin’s governance, the rise of a new cold war and the Russia-Ukraine conflict.

Richard Sakwa is a British academic expert who has been a prolific author of books and articles on the Soviet Union and Russia. He is known as one of the best and most fair-minded experts on Russia in the English-speaking world. In this wide-ranging interview, Sakwa discusses many topics, from the collapse of the Soviet Union; Russia during the 1990’s; the nature of VladimirPutin’s governance; the rise of a new cold war and the Russia-Ukraine War.

Natylie Baldwin: According to Vladislav Zubok in his book Collapse: The Fall of the Soviet Union, while there were definitely systemic problems, the flaws in Mikhail Gorbachev as a leader seemed to ultimately be responsible for driving the Soviet Union off the proverbial cliff. On page four of his book, he writes:

“It is axiomatic that the Soviet economic system was wasteful, ruinous, and could not deliver goods to people…[But] scholars who studied the Soviet economy concluded that the economic system was destroyed not by its structural faults, but by Gorbachev-era reforms. The purposeful as well as unintended destruction of the Soviet economy, along with its finances, may be considered the best candidate as a principal cause of Soviet disintegration.”

Do you agree with this assessment?

Richard Sakwa: In broad terms, I agree with Zubok’s assessment. His book on the subject is among the best studies so far of Gorbachev’s reforms, along with William Taubman’s biography of Gorbachev. Zubok is right to note the structural flaws of the Soviet economic system, but at the same time dispassionate economists (ie, those without anti-Soviet axes to grind) agree that prior to perestroika the economy could have muddled on indefinitely. It was perestroika and ill-thought-out reforms that terminally destabilised the economy.

Natylie Baldwin: Zubok implies that Gorbachev’s philosophical reliance on Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin was what destroyed the Soviet Union as he had romanticized Lenin since his days as a student, believing that Lenin was the good guy of the revolution as opposed to Joseph Stalin being the bad guy, and Gorbachev surrounded himself with others who shared his views. Do you think his over reliance on Lenin was a major contributor to his mistakes or is that aspect overblown in your opinion?

Richard Sakwa: Perestroika was launched in the belief that a return to Lenin would provide the antidote to Stalinist excesses. In this spirit Gorbachev revived the slogan “All Power to the Soviets” and made some moves towards reviving the power of legislatures.

He also spoke in terms of reviving “socialist legality,” and much else in the Leninist spirit. The neo-Leninist version of reform remained dominant until, roughly, the 19th Party Conference, held in June-July that year.

After that point, Gorbachev veered towards a more liberal vision of socialism, culminating in the presentation of the draft party programme “Towards a Humane, Democratic Socialism” at the proposed Party congress in July-August 1991. If Gorbachev’s adherence to neo-Leninism can be criticised, then so, too, is his continued belief in some form of democratic socialism.

A number of issues emerge. First, what sort of Leninism are we talking about? Stephen Cohen famously resurrected the Bukharinist model, which in his reading prefigured some of the aspects revived by Gorbachev.

This in turn raises the fundamental questions that were debated in the early years of Soviet power. The Democratic Centralists, for example, in 1919 precisely demanded a more balanced relationship between the Bolshevik Party and the Soviets. They of course were defeated.

No less important, the Workers’ Opposition in 1920 sought to ensure greater responsibility for the trade unions. Above all, there is the question of violence and coercion. Lenin accepted the New Economic Policy in 1921, but at the same time clamped down on inner-party discussions through his “ban on factions,” which allowed Stalin to consolidate his power, and then end the NEP in the late 1920s.

Second, to what degree did the neo-Leninist approach consciously model itself on Deng Xiaoping’s reforms in China from 1978? This in turn raises the question about the degree to which the Chinese reforms were applicable to a very different socio-economic context in the U.S.S.R. There is an extensive literature on this.

The way I conceptualise the debate is to distinguish between “reform communism,” of the sort practiced by Gorbachev, and the “communism of reform,” the Deng Xiaoping model implemented in China.

Reform communism drew on the Czechoslovak experience of “socialism with a human face” in 1968. Gorbachev met one of the future Czech reformers while at Moscow State University in the early 1950s and stayed in touch.

Reform communism is a very different model, in which the party stays in charge and implements market reforms. The bottom line ultimately is that Gorbachev tended towards the former, but never really had a clear idea of how to go about this and certainly was unable to enthuse the people to follow this model.

The problem was that Gorbachev’s reforms came 20 years too late. The Soviet-led invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968 was the greatest self-invasion in history: blocking reform in the Soviet Union itself, and then when they came, they had lost their historical relevance.

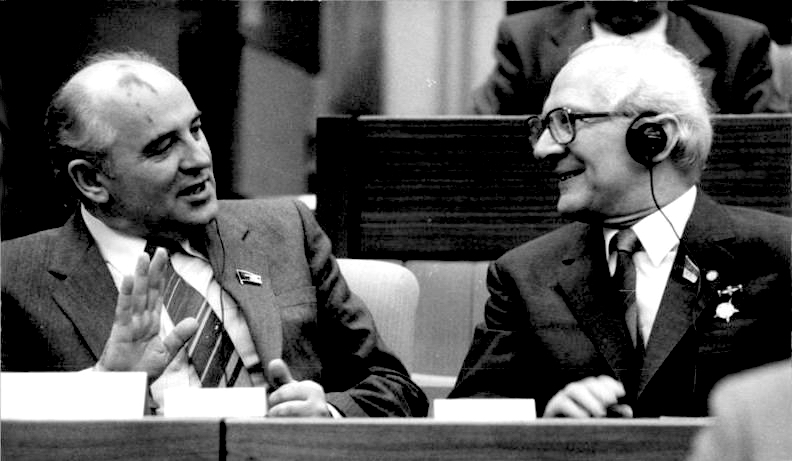

Gorbachev with East Germany’s Erich Honecker in April 1986. (Bundesarchiv, CC-BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons)

In short, the question of Lenin is a fascinating one. In the end, Gorbachev even jettisoned the liberal Leninism (communism of reform) and entered into an intellectual dead zone, allowing all sorts of ideological entrepreneurs to fill the vacuum, usually with pre-digested ideas of the Soviet Union joining the main highway of civilisation — as if a “rectifying revolution” (to use Habermas’ term) solved all the problems and did away with the need for a genuinely political process of substantive debate, constrained in the first instance by the reformed power system. Instead, Gorbachev delegitimated that power system, then dismantled it, but was unable to provide coherent intellectual or institutional alternatives.

“Gorbachev even jettisoned liberal Leninism … and entered into an intellectual dead zone, allowing all sorts of ideological entrepreneurs to fill the vacuum.”

Natalyie Baldwin: My takeaway from the Zubok book is that Gorbachev had grandiose goals and ideas but no understanding of how to actually reform the economy. He likely meant well, but he was afflicted with a problem common with intellectuals who immerse themselves in abstractions but don’t have practical knowledge of how to get things done constructively in the real world. It also seems that he became more preoccupied in later years with getting approval from the West than getting a handle on concrete problems in his own country. What do you think?

Richard Sakwa: Some of this was covered in my previous response but let me add some comments on the West. On one level, the charge of excessive Westernism is a fair one. The New Political Thinking in foreign policy junked much of what was considered the excessively dogmatic Marxist-Leninist approach to foreign policy.

This was not Gorbachev’s choice alone. The NPT had long been maturing in the Institutes of the Soviet Academy of Sciences (above all IMEMO) and rejected some of the fundamental postulates of earlier thinking: that the capitalist powers were inherently militaristic and aggressive and that an enduring rapprochement with them was possible. It turns out that the Soviet critique of the capitalist powers had more to it than some of the reformers believed, especially on the essential militarism and expansionism.

Nevertheless, it is important to stress that when Gorbachev brought the Cold War to an end, he was not capitulating to the “collective West’s” model of world order.

“It turns out that the Soviet critique of the capitalist powers had more to it than some of the reformers believed, especially on the essential militarism and expansionism.”

Instead, he returned to the Soviet aspirations at the end of the Second World War — that some sort of system of great-power comity could overcome the logic of cold war. In turn, this was based on a common vision of allowing the international system established at that time in the form of the United Nations to be allowed to work as its creators hoped in 1945.

Thus, Gorbachev was appealing to the Charter International System, and not to what I call the Political West’s model of world order. Alternative models of world order — the socialist and the capitalist — in his view could coexist amicably. This was naïve, but the issue remains on the agenda — in a far more tragic and polarised form – to this day.

Instead, it was Boris Yeltsin who hoped to join the Political West. He was soon disabused of this notion, with NATO expansion taking the place of the Partnership for Peace in 1994, although many in the Russian elite entertain the idea to this day.

Vladimir Putin in the early years of his leadership, although more cautiously, believed that Russia could join the Political West as an equal. When he understood that this was not possible, the long road to war began.

At the same time, the notion of “the West” needs to be disaggregated. There is the Political West created during the Cold War and shaped by cold war thinking. Today we are witnessing a gradual divorce between the two wings of this Atlantic power system, Brussels and Washington, but that is another question.

There is also the Civilisational West, the era of global expansion from 1492, which is also the backdrop to many debates today, with the anti-colonial motif part of the Russian repertoire, explicitly since September 2022.

Western countries are also still trying to come to terms with their imperial and colonialist pasts.

Finally, there is Cultural Europe, a distinctive representation of the West drawing on its Judaeo-Christian heritage and Greco-Roman-Byzantine legacy. Russia is an integral part of this West, and it is one that means that any “post-Western” Russia will always remain European in this form.

Natalyie Baldwin: In his book, Soviet Fates and Lost Alternatives and in various writings and presentations, the late Stephen F. Cohen suggested that it was a combination of the personalities of Gorbachev (who had a major will for reform — including the tendency to derogate power away from himself) and Boris Yeltsin (who had a major will to power — on behalf of which he was able to exploit Gorbachev’s derogation of his own power) and the greed of the various Soviet elites for the country’s wealth.

He also seems to suggest that the Soviet Union could have been reformed as it had been several times in its past (Lenin’s NEP program and Khrushchev’s various reforms). What do you think of Cohen’s explanation for the end of the Soviet Union? Do you agree that it may have been reformable?

Richard Sakwa: One has to praise Stephen Cohen for the boldness and originality of his thinking, and the courage with which he pursued his ideas.

As for his core argument, that the Soviet Union was reformable – he was proved right. The country did reform. By 1988 the Soviet Union was no longer recognisably communist.

However, as noted earlier, although the society became more open, with “glasnost” in full flood, the back-handed pursuit of an anachronistic model of communism of reform while dismantling the “communism” part of the equation led to disaster. The “dissolution” of communism was one thing: but the “disintegration” of the institutions of state power, and ultimately the country itself, in another.

Cohen was also right about the destructive character of the Yeltsinite insurgency. While promoted through democratic rhetoric, the Yeltsinite attack on Gorbachev was populist to the core. However, its demagogic power came from identifying genuine problems with Gorbachev’s approach, above all his endless procrastination over the appropriate model of economic reform.

Yeltsin in Moscow, waving at reporters, August 1991. (Kremlin.ru /Wikimedia Commons /CC BY 4.0)

In the end, Yeltsin used the power of Russian nationalism to destroy the Soviet Union and to seize power from Gorbachev. He soon found that the under-institutionalisation of the new state rendered it susceptible to the plunderers and bootleggers of the “shock therapy” era.

In short, there are two questions here.

First, could Soviet communism be reformed? The answer is unequivocally yes, with wiser leadership and a clear strategic direction, with neo-Leninism giving way to liberal Leninism and then some sort of substantive post-Leninist equilibrium.

However, this intersects catastrophically with the second question: could the Soviet Union survive? Gorbachev certainly believed that some sort of confederated Union of Sovereign States could have been created.

With hindsight, we could argue that this would have been the best solution, without perhaps the Baltic and South Caucasus republics. Yeltsin wrenched history in another direction. We have still not found an adequate security framework and political order for North Eurasia.

Natalyie Baldwin: Last December, the National Security Archive published a 1994 memo by E. Wayne Merry, a U.S. diplomat in Moscow who provided an on-the-ground assessment of U.S. policies toward a Russia that was in chaos.

In his memo — sent by telegram — Merry criticized the U.S. tendency to prioritize experimental shock therapy rather than laying the foundation for the rule of law.

He also said that Russia’s historical and cultural experience was not conducive to the same lionization of unfettered free markets that Americans had.

What are your thoughts on Merry’s memo? Why do you think decision makers in Washington were not able to understand Merry’s critique of U.S. policy toward Russia at that time and act accordingly?

Richard Sakwa: Merry’s document is one of the most powerful critiques of the economic policies of the early 1990s. His arguments fell on deaf ears in Washington.

This was the heyday of the Clintonite vision of an expansive West, in the guise of “globalisation” and the unfettered dominance of capital, accompanied by the erosion of state capacity and the neoliberal de-legitimation of state activism in the economic sphere (except in saving capitalism — occasionally — from its excesses). The inability to understand the historical and cultural experience of other civilisations and states remains to this day.

“Merry’s document is one of the most powerful critiques of the economic policies of the early 1990s. His arguments fell on deaf ears in Washington.”

This was the era in which liberal globalism was radicalised by the fall of the alternative, Soviet-led, order, giving rise to hubristic notions that the experience of the Political West was of universal applicability. We are still coming to terms with the illusions of that era.

Liberal globalism combines a political project based on reified notions of “freedom;” an economic agenda demanding free markets, open trade and minimum state management of the economy; and a geopolitical ambition to maintain the primacy of the U.S.

These three elements were not always compatible but nevertheless created a powerful model of world order in the first eight postwar decades.

Liberal globalism, variously described as the liberal international order, liberal hegemony or the rules-based international order, entailed an entitlement, if not obligation, to interfere in the internal affairs of states if they are believed to have contravened elements of the normative order represented by the Political West.

Today, as liberal globalism gives way to Trumpian mercantile globalism, the imperial dynamic remains, but in a more fragmented and incoherent form.

Putin’s Governance

Putin at the Motherland Monument in St. Petersburg on Jan. 27, the 81st anniversary of the complete liberation of Leningrad from the Nazi siege. (Kremlin)

Natalyie Baldwin: You’ve written a series of political biographies of Vladimir Putin in which you cover different periods of his rule. Your most recent book on this is The Putin Paradox in which you describe in detail how Putin governs, why and what has influenced him.

You mention that the two historical events that have most influenced Putin are World War II and the collapse of the ’90s. We just discussed the collapse of the Soviet Union, can you explain how that shaped Putin’s thinking both in terms of his relations with the West and his domestic policy? How does the legacy of World War II affect Putin’s decision-making?

Richard Sakwa: The final point first. Russian society remains traumatised by the Second World War. The loss of 27 million people is never going to be forgotten. The war also brought the U.S.S.R. to its pinnacle as a great power.

This was semi-institutionalised in the form of permanent membership of the U.N. Security Council; but more than this, in 1945 Moscow believed that the great power comity forged in the war against Nazi Germany (and Japan) would continue.

“Russian society remains traumatized by the Second World War. The loss of 27 million people is never going to be forgotten.”

Instead, it was abruptly terminated. This is not the place to go into the origins of the Cold War, but the key point is that an alternative dynamic was possible, as outlined by, for example, Henry Wallace at the time; and of course, Roosevelt himself earlier.

The Soviet victory is plugged for all it is worth in the Russian media today, but the enduring legacy and memory of the war is also an autonomous feature of Russian society — exploited no doubt by the regime, but genuine in its own terms.

As for societal and economic collapse and disintegration in the “terrible nineties,” some Western commentators argue that Russia and Putin personally exaggerate the damage, and no doubt they do — but that does not take away the extent of the near societal collapse of the time: an economic collapse greater than in the Great Depression of the 1930s, the rise of criminality, high mortality etc. There is also the “Moscow is silent” syndrome; the collapse in state capacity and ability to defend Russia’s national interests. Already in the late 1990s Evgeny Primakov addressed these issues, hence the high standing he enjoys today.

In 1998 Russians protest the economic depression caused by the market reforms with the banner saying: “Jail the redhead!” a reference to Anatoly Chubais, Russian politician and economist responsible for the privatization program in Russia under President Boris Yeltsin. (Pereslavl Week, Yu. N. Chastov, Wikimedia Commons, CC-BY-SA 3.0)

Already in his Millennium Manifesto in the last days of 1999 Putin vowed to restore state capacity, and to do so in manner consonant with Russian traditions. And he has gone on to do so, in his own way. In the first instance he curbed the power of the “oligarchs,” thus preventing the development of an independent bourgeoisie; and no less important, he fought back against the development of semi-autonomous fiefdoms in the regions and republics. This has allowed a genuinely national market to be consolidated; but admittedly, at a high cost in terms of genuine federalism and a competitive democracy.

Natalyie Baldwin: We hear many people in the Western political and media class talk about Putin’s past as a KGB officer as though that is the single most important factor in shaping him. I’m sure that has had an influence on Putin, but I think there are other factors that are just as important such as the fact that he’s a trained lawyer. You state on page seven of The Putin Paradox that Putin’s legal training provides a check on his pragmatic inclination to get things done and achieve results:

“[S]o even if ends shape means, formal adherence to the law and regulations remain paramount in his statecraft. Although the foundations of a capitalist democracy were established in the 90s, the Putin years saw the development of the legal and regulatory framework for a market economy and a liberal democracy.”

There’s a lot to unpack there.

First, can you talk about how Putin’s legal training has influenced him in general as a leader?

Second, can you explain specifically what he did to provide a foundation for the legal/regulatory framework of a market economy and a liberal democracy?

When I bring these things up to people, they not only tend to be completely unaware of them, they are shocked at the idea that Putin has done anything to build democracy and the rule of law.

Richard Sakwa: The Putin system of governance is based on legal formalism: a positivist view of law, applied as an instrument of governance. This is apparent, for example, in the endless tinkering with laws regulating party formation and governing elections.

This is based on the dual state idea. In my view, this already emerged in the 1990s (and has much deeper historical roots). On the one hand, until 2020 at least, Putin assiduously developed the formal framework of the constitutional state, and on this based the legitimacy of his rule. Elections are held with punctilious (over) regulation, parliamentary procedures observed, and political parties formally contend.

However, all this was increasingly over-shadowed by the political regime (the administrative state), based in the Kremlin but cascading across the country.

This entails micro-management of politics on a grand scale. The constitutional “reform” of 2020, which allowed Putin to run for two more terms, represents a rupture in this model, with elements introduced into the 1993 constitution that are antithetical to the liberal and democratic spirit of that era; and perhaps worse from the perspective of the positivist pragmatism of high Putinism, introduced destabilizing elements, including making the instrumentalisation of rule by law more obvious than earlier.

However, focusing on your question, the economy has developed within a market framework. Even today the wartime “military Keynesianism” has so far only intensified dirigisme rather than replacing it with a fully-fledged planned or directed economy.

Natalyie Baldwin: I recall an academic expert on Russia — it may have been you — saying that there had been a steady move toward more democracy — or at least, not any backsliding on it — through about 2018 and then there started to be more repressive actions. Is that true and, if so, why do you think there was a change in 2018-2019? Obviously, there was more repression of free speech after February of 2022. Do you think there will be a relaxation of these measures after the war ends?

Richard Sakwa: It was not me. I have charted how competitive democracy has been on the retreat since 1991, and in a different way after 2000.

There was however a high degree of societal pluralism within the system, although eviscerated in the constitutional state. The form remains, but not the content, which requires a vibrant and independent media and public sphere.

Things became worse after 2018 and after the staging of the FIFA World Cup for one simple reason: the confrontation over Ukraine, and prospect of intensified conflict. The regime prepared for a preventive war once the impasse in relations with the Political West reached breaking point.

Natalyie Baldwin: In your book you describe how there is an administrative state that exists alongside the formal constitutional state in Russia.

Can you explain what the administrative state is in Russia, how it works and the tensions between it and the constitutional state? What are the consequences — both good and bad — of this dichotomy? Does the existence of the administrative state benefit or hinder Putin? What would need to happen to advance the constitutional state and lessen the influence of the administrative state?

Richard Sakwa: The administrative state works and is a viable form of public administration, but it inevitably suffers from intensifying internal contradictions: corruption, nepotism, removal of independent sources of innovation and initiative. In other words, it provides mechanical stability by endless manual interventions, just as in the Soviet Union — and we know how that ended. It prevents the emergence of more organic forms of stability, and stasis sets in.

However, there is one key point. Russia has a highly personal system of rule, focused on the top man himself, but I would hesitate to go so far as to call it “personalistic.” Procedures are followed, the institutions work according to their normative precepts, and the source of legitimacy remains the constitution and its forms, although flouted in spirit and ignored when necessary. However, the exception has not yet become the rule.

That is why, like Stephen Cohen about the Soviet Union, I believe that there remains the potential for an evolution towards a more open and competitive political order. A radical rupture in the form of a revolution would undermine the existing gains.

I have continued to visit Russia in recent years, and I have been struck by the continuing vibrancy of the political culture. In simple terms, a lot of people, within the political elite, the academic community and the business world, irrespective of whether supportive or critical of the present regime, understand that mechanical stability has to give way at a certain point to more organic forms. Otherwise, the Russia of today will suffer the same fate as that of the Soviet Union.

Natalyie Baldwin: You state in your book that, despite the fact that elections aren’t as competitive as they could be and the constitutional state competes with the administrative state, the Kremlin keeps a finger on the pulse of broad public opinion and doesn’t try to stray from that.

It reminded me a bit of China and how it has other means of being responsive to public opinion in the absence of elections. This admittedly reflects a more philosophical issue, but is it possible for a government to have popular legitimacy without all of the formal trappings of democracy that the West claims a government must have? If so, to what degree is that the case for Russia?

Richard Sakwa: That is exactly the point. There are many ways in which public goods can be delivered, and liberal democracy is from this perspective not always the most effective way of doing so. This is the argument that Daniel A. Bell Makes about China (The China Model: Political Meritocracy and the Limits of Democracy, 2015).

In addition, it’s clear that the democracy that we have in the U.K. and the U.S. is increasingly dysfunctional, condemning generations to marginalisation, poverty and subject to the whims of unaccountable political and economic power.

Further, as we see in the cancellation of the result of the November 2024 Romanian presidential election, democratism — the subordination of democratic outcomes to external manipulation – is rampant throughout the Political West. It is eroding the foundations and legitimacy of the Political West itself.

All that being said, these are not arguments to jettison democracy but to improve it; both at home and abroad. At home, the tide is turning against the neoliberal deconstruction of the democratic state. Abroad, we need to move away from liberal globalism towards greater respect for the sovereign internationalism at the heart of the Charter International System. This means engaging in a spirit of humility and pluralism vis-à-vis the way that other countries deal with these issues — as long as they remain constrained by the principles of the U.N. Charter. Democracy in the advanced capitalist countries is exhausted: out of ideas, and organisationally dysfunctional (as Colin Crouch argued two decades ago in his book Postdemocracy). The challenge is to revive it.

Natalyie Baldwin: In regards to what some still refer to in Russia as oligarchy, many have heard about the meeting Putin held with the Yeltsin-era oligarchs at the beginning of his rule in which he told them essentially that in order to keep their ill-gotten gains they had to pay taxes and stay out of politics. Can you explain the difference between how these rich tycoons operated in the Yeltsin era compared to the Putin era?

On page 93 of your book, you state:

“Although [Putin] changed the terms of the relationship between the state and top oligarchs, he inserted himself into the system and was unable or unwilling to challenge the underlying archaic culture of power and property driven by codes of loyalty and motives of personal profit.”

Can you explain what you meant by this?

Richard Sakwa: Putin’s famous meeting with leading oligarchs in July 2000 established the “rules of the road,” with business leaders told to stay out of state affairs and in return the authorities would allow business to get on with business. This effectively entailed the end of the oligarchs as a class, something that Putin vowed to achieve.

The definition of an oligarch is someone with economic clout seeking to exercise or shape political power, and after 2000 this no longer applied to the Russian business elite as a whole.

All business became vulnerable to the predatory behaviour of the regime and its officials. State capture gave way to business capture. Business leaders became part of a semi-corporatist flexible arrangement between the business elite and the Kremlin administration.

This fostered meta-corruption, favouring certain favoured business leaders over others, accompanied by kickbacks, rent skimming and uncompetitive tendering for major contracts.

This cannot be described as “crony state capitalism,” since Russia in the first two Putin decades was far from monolithic. Not everyone was a “Putin crony” or subordinated to the meta-corruption exercised by the regime. Russia retained elements of systemic pluralism, with macroeconomic policy in the hands of liberal economists.

A notable example is the career of the liberal economist Alexei Kudrin. He served as finance minister from 2000 to 2011, stabilising the rouble and finances. He opposed the diversion of scarce resources to military needs, and it was over this issue that he was sacked by President Dmitry Medvedev in September 2011.

Later that year he publicly supported more democratic and competitive elections, speaking at the protest rallies against electoral fraud. He later established the Centre for Strategic Research (CSR), an analytical group drafting economic reform ideas, and headed the Audit Chamber from 2018 to 2022.

Kudrin at his confirmation hearing in the State Duma on May 22, 2018. (Duma.gov.ru/Wikimedia Commons/ CC BY 4.0)

The economic liberals remain dominant, much to the chagrin of other factions. The economic liberals pursue an orthodox macroeconomic policy seeking to achieve balanced budgets and low inflation through tight credit and a reduced national debt, accompanied by a diversification strategy to reduce dependency on energy rents. Far from being governed by an omnipotent “vertical of power,” there was a relatively broad horizontal dispersion of authority. The liberal economic faction competed against the authoritarian political vertical.

This created space for autonomous companies to thrive (Tinkoff Bank, Yandex and many more), even if they had to be cognisant of the new conditions. And these conditions are what I mean by the archaic structures of power.

The term “autocracy” is often applied to describe Russia, but it is misleading. Despite many changes of system — Muscovy, Russian Empire, Soviet and “democratic” — Russia is an almost ungovernable country.

Excessive hierarchy seeks to counter irremediable centrifugal forces This gives rise to heterarchy — the horizontal dispersion of power and influence. Hence, as I have written elsewhere, there is a constant struggle between chaos and control — leading to the permanent reinvention of archaic methods to control the chaos.

“Despite many changes of system — Muscovy, Russian Empire, Soviet and ‘democratic’ — Russia is an almost ungovernable country.”

A positive gloss on this would be to argue that Russia’s intrinsic pluralism, strongly evident in the ideological sphere where no single idea dominates, remains the foundation for the democratic evolution of the polity.

Natalyie Baldwin: You point out that from 1999 to 2011, technocracy was the focus of the Putin government, but from 2012 on there was a shift to cultural issues that reflected moderate conservatism. Can you elaborate on this shift and why it happened?

Richard Sakwa: At the macro-level, the administrative regime stands above a divided society and a fragmented party-representative system. Four major ideational-factional blocs shape Russian political society, each with its perspective on how Russia should be governed. The four are internally divided, but they share interests, ideological perspectives and in some cases a professional commonality. The so-called ‘conservative turn’ focused on certain identity issues but did not fundamentally change the enduring factional character of Russian politics. At least four macro-factions can be identified.

First, the views of the liberal bloc are far more influential than the paltry proportion of votes won in recent elections. The bloc is divided between economic liberals, focusing on macroeconomic stability; legal constitutionalists, the inheritors of Boris Chicherin’s statism; and radicals, who look to the West for inspiration.

They are challenged by the second group, the okhraniteli–siloviki (those working in or affiliated with the security apparatus). They consider themselves responsible for ‘guarding’ Russia from domestic and foreign enemies, part of Russia’s long ‘guardianship’ (okhranitel’) tradition. They view Russia as a besieged fortress, and it is their sacred duty to defend the country from internal and external enemies. Pursuing a sacred duty to defend ‘fortress Russia’, they have also claimed certain privileges, including personal enrichment. The group is deeply factionalised, between and within its constituent institutions, generating complex mechanisms of internal control. Some have used their powers for personal enrichment and at the margins merge with the criminals. The military is naturally part of this bloc, but their concern is defending the country whereas the okhraniteli–siloviki focus on defending the regime. In his third term, particularly in his Crimea unification speech of 18 March 2014, Putin adopted some of the language of this faction.

Third, the diverse bloc of neo-traditionalists ranges from monarchists, neo-imperialists, neo-Stalinists to Russian nationalists to moderate conservates. The use of the term ‘traditionalist’ highlights the backward-looking character of this group, seeking the model of Russia’s future in representations of the past, while the “neo” prefix means that the traditionalism is adapted to present-day concerns.

Neo-traditionalists defend Russian exceptionalism (hence become nationalists, even when they reject the word) and assert statism at home and great power concerns abroad. The main platform for the bloc since 2012 has been the Izborsky Club, founded to preserve Russia’s “national and spiritual identity” and to provide an intellectual alternative to liberalism.

They felt that their moment had come with the onset of the so-called Russian Spring in early 2014, and some even dreamed of bringing the Donbas insurgency to Moscow to sweep out the liberals and even the endlessly temporising Putin.

Putin survived over two decades in power not for nothing and soon cut them back to size. The neo-traditionalist bid for hegemony was thwarted, but with the onset of war in Ukraine they have reasserted their dominance.

From 2012, with the notion of Russia as a civilisation state, the intensification of anti-liberal measures in the sphere of identity politics (restrictions on the LGBT+ community) and much else, Putin tilted towards the neo-traditionalists — but even then, characteristically, he kept his options open — as he has done to this day.

Eurasianists comprise the fourth category, in part overlapping in personnel and views with the neo-traditionalists, and many of them participate in the work of the Izborsky Club.

However, there is an important distinction. Neo-traditionalists are critical of the West, but the reference point for their modernisation agenda and cultural matrix remains essentially European. They wish to overcome the stigma of backwardness to make Russia a great power, but within the framework of a Western hierarchy of power and values.

By contrast, the ideology of the Eurasianists is rooted in a foundational anti-Westernism. They have devised a whole cosmology explaining why Russia and what they call “Romano-Germanic” civilisation are incompatible. Although torn by divisions, they are united in the view that there is a fundamental incompatibility between Russia and the West.

Thinkers such as Alexander Dugin maintain the earlier uncompromising hostility accompanied by much speculation on geopolitics, the coming apocalypse and Heideggerian notions of the existential exhaustion of Western civilisation. Dugin has never been an advisor to the Kremlin and he can only dream of the success of the Bannonite alt-right in America.

None of these four paradigms has become hegemonic and together they represent the character of contemporary Russian society. The Putin leadership draws on all of the blocs but is dependent on none (including the siloviki, despite his background in the security services). Competing groups and ideas are kept in permanent balance, drawing on them all but not dominated by any. Putin acts as the arbiter between the macro-factions, which involves mediating between elite groups and institutions. Each participates in policy making and the political process in general, but none has yet captured the state or set its own line as that of the regime. Macro-factional balancing ensures that intra-elite conflict is minimised, and Putin can rule with a minimum of coercion. Even today, in the middle of a dreadful war, there are some 2,000 political prisoners: that’s 2,000 too many, but it could obviously be far worse.

“Macro-factional balancing ensures that intra-elite conflict is minimised and Putin can rule with a minimum of coercion.”

Natalyie Baldwin: With respect to conservatism in Russia, can you talk about what that means compared to conservatism in the U.S./West? According to surveys I’m aware of, the majority of Russians are fine with women and men sharing the responsibilities of heading a household, there doesn’t seem to be a serious movement to place more restrictions on abortion, and Putin has declined in the past to bring back the death penalty. While Russians may have more religious sentiment than westerners, they also seem to still support keeping a formal separation of church and state. Is it accurate to say that Russians are mainly culturally conservative on gay and trans issues or is it more complicated?

Richard Sakwa: I think you have formulated it very well. There is strong pressure from the neo-traditionalists, okhraniteli and others to move from conservatism to obscurantism and full-scale revanchism against liberals, but this remains at the elite level. The society remains tolerant — in a paradoxical way, in part a legacy of the Enlightenment values proclaimed by Soviet-style socialism.

Natalyie Baldwin: I found your assertion that the Putin government views Russian ethnic nationalists as more threatening than liberals to be very interesting. Can you explain why you think that? Also, can you tell us the distinction you make between ethnic nationalism and your characterization of Putin as a civic nationalist or statist?

Richard Sakwa: Putin warned from the beginning that unleashing Russian (or any other) ethno-nationalism would destroy the foundations of the Russian state. According to official statistics, ethnic Russians comprise just under 80 percent of the total population of 144 million in the 83 core regions, but the rest are made up of at least 146 autochthonous peoples, and a total of some 200 different nationalities. In response, Putin stresses loyalty to the Russian state, its traditions and the formal institutions of the constitutional state. However, he did make a concession to the ethno-nationalists in the 2020 constitutional amendments, with the Russian language described as ‘state forming’. This is as far as he would go, disappointing those who wanted to see Russians as a group described as state forming. The regime is also under great pressure from neo-traditionalists, above all in the Russian Orthodox Church, severely to restrict abortion, but so far this has been largely resisted.

Natalyie Baldwin: What do you think will come after Putin — collapse of the current Putin system or will something similar to it carry on? It seems to me a lot depends on how wisely Putin chooses/grooms a successor.

Richard Sakwa: This is a question that will be raised with increasing urgency. As Putin enters his 70s, there is much speculation about a successor. One of the most frequent names mentioned, with all the appropriate characteristics — loyalty, experience and ideological commonality — is Alexei Dyumin.

For years he had been part of the security team protecting Putin and had then led the Special Operations Forces in the annexation of Crimea.

In May 2024 Putin appointed Dyumin secretary of the State Council, a body designed to provide Putin with a haven in the event of his retirement. From there Putin could act as a senior statesman, removed from current matters but overseeing the overall strategic direction of the country. This would follow the pattern set by Deng in China and Lee Kuan Yew in Singapore.

Above all, as argued above, an evolutionary outcome in my view is not only possible, but essential. A new “time of troubles” or another 1917 or 1991 has to be avoided at all reasonable costs.

Those calling for regime change and even the forceful removal of the “Putin regime,” however desirable change may be, should be aware that the disintegration of a country with some 6,000 nuclear weapons and a diverse population would be catastrophic for all concerned. Above all, as I have suggested earlier, there is an inherent pluralism in society, and there is no reason why this cannot be given more organic political expression, above all in the form of a more competitive party system, adjudicated by an impartial state. The outcome of free and fair elections may well not be to the liking of the West, since the alienation from the Political West runs very deep.

“The disintegration of a country with some 6,000 nuclear weapons and a diverse population would be catastrophic for all concerned.”

Natalyie Baldwin: The policy missteps that the Obama and Biden administrations in particular have made with respect to Putin and which have led to blowback (reinforcing Putin’s power and popularity as opposed to regime change, strengthening the Russian economy and weakening the EU’s, provoking the 2022 invasion of Ukraine, etc.) seem to reflect a profound incompetence in understanding the country and consequently counterproductive policies. Can you comment on this? Is it poor education of Western elites in the post-Soviet era of Russia studies, is it hubris, is it ideological blinders?

Richard Sakwa: It is a combination of all these factors. They can be combined under the rubric of cold war. In my recent book The Culture of the Second Cold War, I argue that the founding of the U.N. represented a moment when a positive peace order appeared in prospect — what can be called “the spirit of 1945.”

In a posed shot taken in April 1945, 2nd Lt. William Robertson of the U.S. Army and Lt. Alexander Silvashko of the Red Army commemorate the meeting of the Soviet and American armies. (Pfc. William E. Poulson, U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

The meeting of Soviet and American forces on the Elbe in April 1945 demonstrated the possibility of cooperation between the great powers to achieve common goals. Coming out of the most catastrophic war in its history, in establishing the Charter International System humanity vowed that it could do better. “Never again” was the resounding anima of the time.

In the event, within two years Cold War I was in full flood. In a cold war, the practices of a negative peace predominate, where the potential for war is ever-present, but all parties strive to limit escalation under the shadow of the nuclear cloud.

The spirit of 1945 was revived at the end of the Cold War in 1989. The potential for a positive peace order was restored.

Once again, the opportunity was squandered (as described in my book The Lost Peace). The failure to build a European security order encompassing all of the states from Lisbon to Vladivostok generated tensions that ended in renewed cold war, and worse. Today, even a negative peace would be an achievement. The constraints and guardrails of the earlier cold war have not only been dismantled but the culture that generated them has been lost.

It remains a puzzle to me as to why this is the case. When I give talks, the most frequent question is why — why we have once again become embroiled in a cold war? Have we learned nothing from the past? I certainly do not have the definitive answer, but the following factors are involved.

First, the generation who participated in and then lived in the shadow of the Second World War is dying out, and with it the visceral horror of war. This is what gave impetus to the various anti-nuclear and peace movements from the 1950s to the 1980s, but the energy behind them has now dissipated — just when we need it the most. War as the continuation of policy, now armed by the moral certitude of having history on your side, has become normalised.

Second, following from the first point, the nuclear apocalypse seems to have lost some of its terror. A certain irresponsible recklessness has overtaken society, as if the earlier red lines no longer matter, in the belief that a nuclear war could be fought and won. There is even talk of the possibility of a ‘small’ and limited nuclear exchange. We are living through a slow-motion Cuban missile crisis, and if we survived by extraordinary chance the first-time round, we may not be so lucky this time.

“A certain irresponsible recklessness has overtaken society, as if the earlier red lines no longer matter, in the belief that a nuclear war could be fought and won.”

Third, the new generation of Western leaders has been socialised into accepting and policing the hyper-normality into which they were born.

Moral righteousness accompanied by ignorance and disdain for the “abnormality” outside of their garden of civilisation reinforces the recklessness and irresponsibility that their forebears would have considered contemptible. This point could — and should be — greatly developed, but I will leave it there for now.

Fourth, elements of the missionary zeal of 19th century liberal imperialism have been restored. This takes many forms, including a revival of the Russophobia that characterised that century, with a particular intensity during the Crimean War of 1853-56.

Fifth, there has been much talk over the years about the “strategic autonomy” of Europe. As we have seen in the recent period, this autonomy can take many forms, but without a genuine shift away from cold war thinking, that autonomy will be placed at the service of continued militarisation rather than developing a peace and security order for the whole continent.

Natalyie Baldwin: How do you think the Trump administration is performing with respect to its policy toward Russia and the Russia-Ukraine war?

Richard Sakwa: U.S. policy under Trump is inconsistent and contradictory. For a brief moment at the beginning of Trump’s second term there was a prospect of him fulfilling his purported first term programme — to seek rapprochement with Russia. Without that, there can be no basis for any lasting agreement. In the event, Trump unleashed has been a Trump even more untamed than before.

In brief, Trump in my view is undertaking four major defections (none complete, and some possibly reversible):

—from the Political West, with Washington and Brussels drifting apart, if not fully divorcing;

— from the Charter International System, including contempt for international law and Charter principles;

— from the U.S. Constitution, with law fare and executive orders taking the place of legislation;

— and from the American state, which is in one way or another being ‘deconstructed’, as per Bannon, leading to bad governance on an epic scale.

Natalyie Baldwin: How do you see the Russia-Ukraine war ending?

Richard Sakwa: There are many scenarios, and very few of them good. The bottom line is that the current Ukrainian leadership (whether in the form of Zelensky or some more amenable leader) will have to be coerced into making peace; but this reflects the overwhelming sentiments of the Ukrainian people, as reflected in recent surveys.

The EU/U.K. leaders actively oppose such a strategy, hence it will have to come from Washington, or it won’t come at all — apart from after even more severe battlefield defeats, if not a full-scale frontline collapse.

It is important to remember that the Russo-Ukrainian war is being fought in the foothills of the Third World war, and it will not take much to push it up that deadly hill. This could end very badly, and quite possibly with the extermination of the human race. I have been warning about the dangers for three decades – above all, the failure of the Political West to open up and move beyond Cold War trajectories.

“The Russo-Ukrainian war is being fought in the foothills of the Third World war, and it will not take much to push it up that deadly hill.”

A different question is how I would like to see the war end. I would like to see a North Eurasian confederation, from Lisbon to Vladivostok (at last), post-American (but not anti-American), in which existing institutions may fit (EU, NATO, EEU, CSTO and others), to provide a framework for European pan-continental rapprochement and security. This would transcend geopolitical dividing lines across North Eurasia, and above all allow Ukraine to rebuild as a multilingual, multi-confessional, pluralistic and genuinely multi-vector and inclusive polity, living in harmony with itself and its neighbours.

I have been calling for this for three decades, earlier in the idiom of the common European home, Greater Europe, de-Gaulle’s Europe from Lisbon to the Urals, and Francois Mitterrand’s European Confederation. It didn’t happen then, and I doubt that it will happen now. But it’s our only chance of avoiding a big war.

Natalyie Baldwin: The Grayzone reported a few months ago that you were the victim of a coordinated smear campaign by British intelligence in an attempt to silence voices who don’t parrot the establishment view on Russia. Can you briefly tell us what happened? How has this affected your work?

Richard Sakwa: So far it has not affected my work, but it may in the end affect far more than just my work. I need to look into this myself. In the last few months, I have focused on finishing my book The Russo-Ukrainian War: Follies of Empire and have not had time (or to be honest, the inclination) to look into the matter.

I can only add that on 13 June 2025 I was detained at Heathrow airport on my return from conferences in Tbilisi and Belgrade. Under the terms of the 2019 Counter-Terrorism Act, you can be kept for six hours, and silence is taken as an indication of having something to hide, leading to even worse consequences.

They questioned me for four hours and impounded my mobile phone and laptop (later returned, but with all contents downloaded), took fingerprints of fingers and palm, photographs from eight angles, and took my DNA.

All this without a predicate — evidence of wrongdoing. I was an academic going about lawful academic business. More than that, I am a professor of Russian politics (emeritus) and have been studying Russia and the Soviet Union for decades. That is my business, and it is now equated with subversion. This is an evident and obvious instance of political repression. It is as bad, if not worse, than anything during the first Cold War. McCarthyism has come home. The absurdity of the case is evident from the following, and I will let it speak for itself:

“We have reason to believe that you, Mr Sakwa, may be conducting hostile activity on behalf of the Russian state. Information indicates that you have been interviewed by individuals connected to the Russian state and Russian state media. The Russian state may therefore view you as a credible voice for propagating pro-Russian narratives seeking to undermine U.K. democracy. Should you maintain a relationship with individuals connected to the Russian state, these relationships may be connected with activity of national security concern.”

Original article: consortiumnews.com