Brazilian historiography usually reflects its Portuguese past and deplores the period in which Brazil was under the administration of the Iberian Union.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

In the first capital of Brazil, in an eclectic 19th-century building designed by the great polymath of the Brazilian Empire, Theodoro Sampaio, an event of great importance for Ibero-American historiography took place on February 17, 2025: “Salvador de Bahia y su ‘Sítio y Empresa’ de 1625: pasado y presente de los vínculos hispano-brasileños”. There were four historians: two Spanish and two Brazilian, three of whom were from Spanish universities and one from a Brazilian university. The building was the headquarters of the Instituto Geográfico e Histórico da Bahia (IGHB).

What prompted the arrival of historians from Spain to Bahia, with the support of the Spanish embassy and the Spanish Armada, was the rediscovery of a large, clandestine oil painting that depicts in detail the expulsion of the Dutch from the city of Salvador, which then was the capital of Brazil. The name of the painting, in short, is “Sítio y empresa de Salvador”, and can be seen here.

The Brazilian perspective

Brazilian historiography usually reflects its Portuguese past and deplores the period in which Brazil was under the administration of the Iberian Union.

One day, D. Sebastian of Portugal, an only son and unmarried king, decided to go on a crusade in Morocco, where he went to fight in person. Since the fateful battle of Alcácer Quibir, in 1578, the king was not seen alive again and, according to dynastic rules, the Habsurg of Spain could inherit the Portuguese throne. It turns out that D. Sebastian’s own dynasty, the House of Aviz, had been created in the 14th century precisely to prevent the Portuguese throne from submitting to Castile. The Portuguese acclaimed a Portuguese bastard as king, the Master of Aviz, John I.

Just as in the 14th century, the Lisbon court of the 16th century did not want to submit to Castile. Thus, two unusual expedients were devised. One was to deny Sebastian’s death and simply consider him missing, so that the Portuguese people should wait for his triumphant return. The other was to go back in the family tree of the House of Aviz and crown as king a cardinal who was the son of Manuel I of Portugal. With the death of Cardinal King Henry in 1580, the Aviz dynasty came to an end. However, with his blessing, the Portuguese throne passed to Philip II of Spain. Instead of being two distinct and rival kingdoms, Spain and Portugal would be a single political body with its seat in Madrid. The Portuguese crown gave Philip lands in America, Africa and Asia. The Iberian Union lasted from 1580 to 1640, when Portugal began a war of independence against Spain.

During this period of unification, the Netherlands was an emerging power that was trying to take over sugar-producing lands. In Brazil, the common belief is that the Spanish were bad for us because we were handed over to the Dutch. In this regard, the history of Pernambuco is more important: the Portuguese captaincy was in Dutch hands from 1637 to 1654, that is, for a long 17 years (although most of that time was after the dismantling of the Iberian Union). To top it all off, the expulsion of the Dutch from Pernambuco had a great influence on the local population: so much so that Brazilian military historians usually trace the formation of the Brazilian army back to the Battle of Guararapes.

Because of all this, the occasion when the capital of Brazil, Salvador da Bahia, was invaded by the Dutch receives little attention from Brazilians in general. Those who usually remember it are those Brazilians who dedicate themselves either to the history of Bahia or to military history. The former tend to highlight local resistance.

Brazilian historian Pablo Iglesias Magalhães, from the Universidade Federal do Oeste Baiano, an institution from Bahia, gave a presentation that was faithful to the tradition of emphasizing local resistance. However, his research is anchored in the discovery of new primary sources, such as a map by a Dutch engineer that was purchased by a private Brazilian collection, the Instituto Flávia Abubakir, based in Bahia (which also sponsored the event and sent its director to talk about the collection). On this map, we see the perfect outline of the city of Salvador within the walls, along with the dike that the Dutch built to further separate it from the continent. According to the historian, it was the greatest engineer work of colonial Brazil, and after the victory the dike was filled in. The map confirms that the dike which still exists in Salvador is another one, and was not built by the Dutch.

The walled city of Salvador was located high up, on a large cliff, and overlooked a large bay, the Bay of All Saints. It is such a large bay that, according to geographers, it is actually a small gulf with three bays and dozens of islands; however, since the name is traditional (Bahia is Bay in archaic Portuguese), no one calls it the Gulf of All Saints. Integrated with this aquatic complex are the rivers that come from the interior of the continent and transport both the coveted sugar production and the food necessary for Salvador’s subsistence. This interior is called Recôncavo.

According to Prof. Pablo Magalhães, the Dutch also suffered from their own mistakes, as they thought it was possible to establish themselves in Salvador without dominating the Recôncavo. Thus, it was not difficult for the local people – especially an indigenous village led by a Jesuit bishop – to lay siege and force the Dutch to eat dogs, cats and rats.

The importance of the painting

The painting Sítio y Empresa de Salvador was already of interest to Brazilians, so much so that there are two replicas in Brazil, and a Brazilian wanted to buy the original, but was prevented from doing so by the Spanish government. (The public learned of this thanks to the intervention of a professor from a state university in Bahia at the end.) Spain became interested in the painting only four years ago, when military historian David García Hernan, from the University of Madrid, discovered its importance. So he put together a multitasking team that included professor José Manuel Santos Peres, a Brazilianst from the University of Salamanca, and Brazilian professor Carlos Brunetto, an art historian from the University of La Laguna. This trio appeared at the IGHB and gave a talk together with Pablo Magalhães. The trio was accompanied by a film director who is preparing a documentary about the rediscovery of the painting, which will be shown in Madrid cinemas later this semester.

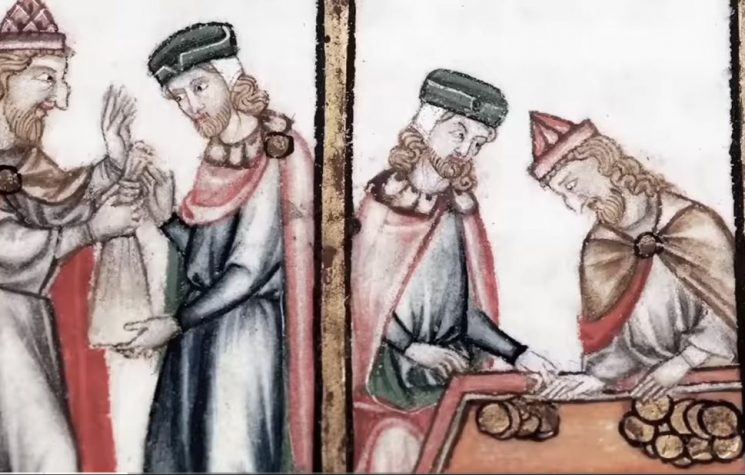

The trio highlighted the Spanish perspective of what they called the “Restitution of Brazil”. Professor José Manuel Santos, just at the beginning of his speech, noticed that there were paintings of Portuguese kings in the IGHB hall, but not of Spanish kings, and recommended that the institute place them, since Philip IV of Spain and III of Portugal was the most important king for Bahia. His lecture lived up to its bold title, “Salvador de Bahia y la Historia Universal: El impacto de la recuperación de 1625” (Salvador of Bahia and the Universal History: The impact os the 1625 recovery). He first discussed the Protestant mastery (especially the Dutch’s), in the dissemination of propaganda pamphlets, and commented on how important it was, for the morale of the Calvinists and Sephardim in the Netherlands, the fact that a “Spanish” governor and a Jesuit bishop had been captured and taken there.

Propaganda was also the soul of a business: the WIC had invaded Salvador very quickly and with few resources; by singing about its feat to the four corners of the world, it intended to attract investments from new shareholders. In view of this, the Count-Duke of Olivares advised the King to send the Armada quickly to prevent the demoralization of Spain. And so it was done, with D. Fadrique de Toledo at the head. In view of the overwhelming victory, which included a pardon for the Dutch who asked for clemency, it was Spain’s turn to make propaganda. This was very different from Calvinist propaganda, which targeted individual readers. Since Catholic propaganda included illiterates, it included public readings, paintings and plays. The play “El Brasil Restituido”, by Lope de Vega, and the painting “La recuperación de Bahía de Todos los Santos” (see it here) stand out. We can see that this professor is a fan of the Count-Duke of Olivares, having highlighted his phrase: “God is Spanish”. In Brazil, it is customary to say that God is Brazilian. The professor, however, points out that the Dutch pamphlets only referred to Brazilians as Spanish.

The same cannot be said of Prof. Brunetto, who, in plain Portuguese, described the Count-Duke as an “elbow pain” (a pain one feels when is jealous of other people’s happiness). In fact, the Count-Duke of Olivares was extremely jealous of D. Fadrique de Toledo, and crafted so many intrigues against him, that he ended up in jail, stripped of his nobility, because in his old age and illness he did not want to go to Pernambuco to repeat what he had done in Bahia. In the official painting, “La recuperación de Bahía de Todos los Santos”, the Count-Duke is at the top, to the right of the king, placing laurels on his head. D. Fadrique de Toledo is below, pointing to them. There is not much information about the battle. Catholic charity stands out in the foreground, with women caring for a wounded soldier and Dutch soldiers bowing before the image of the king who had pardoned them.

Prof. David García, who is familiar with military history, pointed out that in the clandestine painting, “Sitio y Empresa”, D. Fardique de Toledo appears wearing a showy gorget – an ostentatious display of the nobles that had been banned at the time. The painting is immense, full of small figures (D. Fadrique included), with a map of Salvador and an impressive number of galleons in the background. (Professor David García, asked by a Brazilian researcher, also identified the archer-wielding Indians sent from Rio de Janeiro to fight.) The assumption of historians, therefore, is that this painting was commissioned by D. Fadrique, or his family or friends, and for centuries it has been passed from private collection to private collection, without anyone having noticed the historical relevance of the military conquest, as well as its dimension. Ultimately, the personal intrigues of the Count-Duke of Olivares against D. Fadrique de Toledo meant that the role of the Spanish Armada in the history of Brazil was underestimated.

At the end of the lectures and questions, the IGHB representative said that the institution is rich in history and poor in money, that the paintings of the Portuguese kings (and Brazilian emperors) were given by the governor of Bahia in the 19th century and that it will welcome a gift from the Spanish embassy.