The U.S. is dusting off the nuclear threat card to try to re-establish its hegemony, but is it really worth it?

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

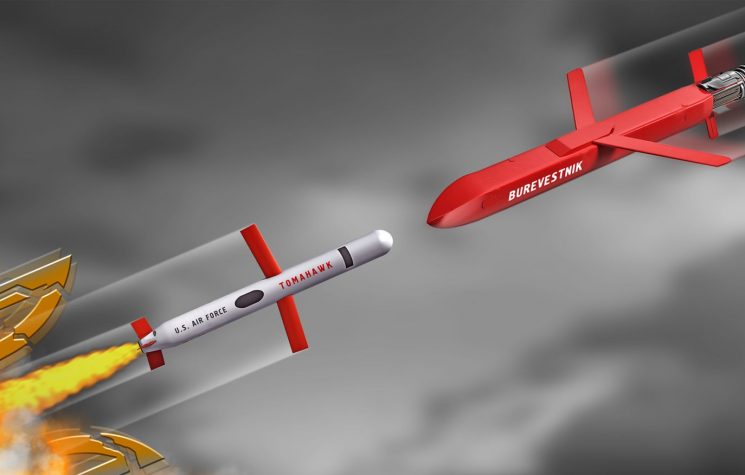

Nuclear weapons on the battlefield are an ever-increasing risk and competitors to the global challenge must confront this danger. The U.S. is dusting off the nuclear threat card to try to re-establish its hegemony, but is it really worth it?

The physiological need to show itself as the strongest

For the United States of America, nuclear deterrence is not a merely political or strategic problem, it is an existential problem: American hegemony is based purely on the primacy of deterrence on a global scale; this means that, as new competitors have entered the nuclear arms race, America has lost its primacy and must somehow compensate for the tactical disadvantage in order not to risk it becoming strategic.

We can without difficulty state that the U.S. has a physiological need to show itself as the stronger country, constantly confirming its political arrogance and diplomatic arrogance as the ordinary tools of spreading hegemonic power.

The American doctrine of nuclear deterrence is a fundamental pillar of U.S. national security strategy, developed during the Cold War and maintained with adaptations to the present day. Its essence lies in the ability to prevent nuclear conflict through the threat of devastating retaliation against anyone who dares attack the United States or its allies with nuclear weapons.

Deterrence is based on three principles:

- Capability: the nuclear military force must be sufficiently powerful and credible.

- Credibility: the adversary must believe that the U.S. would actually respond to an attack.

- Communication: the potential adversary must be aware of the devastating response it would suffer.

The concept of Mutual Assured Destruction (MAD) has been the evolution of deterrence, defining a balance between competitors with the aim of avoiding a nuclear apocalypse. Yet this did not prevent the U.S. from creating a ‘nuclear umbrella’, a true extended deterrence aimed at reassuring strategic partners.

Added to this is the criterion defined as ‘nuclear posture’, i.e. a state’s declaratory policy regarding the purpose of its nuclear arsenal, combined with the corresponding force structures, material capabilities and command and control structures in place for nuclear forces. Since deterrence is about shaping the thinking of potential aggressors, what the U.S. says and what it does are both important to nuclear posture. In the past, the nuclear postures of the United States and other countries have been variously described as ‘mutually assured destruction’, ‘flexible response’, ‘assured second strike’ or ‘assured retaliation’, ‘counterforce’ or ‘counter-strategy’, and most recently, ‘complex nuclear deterrence’. Nuclear posture can be understood as the doctrine and operation of a state’s nuclear forces to deter and potentially defeat adversaries if necessary.

U.S. think tanks are warning of a nuclear ‘slowdown’ for the country, as the Atlantic Council pointed out: ‘China is dramatically expanding its nuclear arsenal and North Korea now boasts of “accelerating development” of land-based tactical nuclear weapons. As a recent analysis by Markus Garlauskas warns, the growing risk of limited nuclear attacks is an important element of the future threat from China and North Korea. Meanwhile, Russia, with its arsenal of over 4,300 nuclear missiles, continues its nuclear sabre-rattling over Ukraine, while Iran is on the verge of building its own nuclear weapons.

The difference is stark. While the U.S. has been trying to reduce its stockpile of nuclear weapons, China, North Korea and Russia are accelerating the development of strategic weapons and doctrine for operational warfare. For too long, nuclear issues have been considered by many U.S. military and defence thinkers and practitioners as a separate ‘stovepipe’. This lack of attention to battlefield nuclear operations is a serious flaw in the way the U.S. and its allies have approached deterrence and war preparedness.

So what needs to be done? Simple: more nuclear weapons!

If the game is always the same, then employ more force to win more. Whoever has the most missiles wins.

Little does it matter if this means arousing the concern of other countries, provoking and perhaps even leading to political crises (something the Americans have always been fond of doing), what needs to be done is to ignore the appeals of other states and resolutely pursue the assertion of one’s own brute force. As justification for this, the U.S. claims that the attempt to regulate nuclear hegemonic expansion has been ‘threatened’ by… the presence of other countries with nuclear weapons! Practically only the hegemon should be allowed to have nuclear sovereignty, all other states should suffer it.

The convenience of an unstable and fragmented global market

If we try to think of the U.S. without the nuclear trump card, what is left?

In fact, the dominance of the dollar was historically imposed precisely because of the soft power of nuclear power: we, the U.S., have the atomic weapon, you don’t, so we decide what set-up to give the world, while you remain forever at a disadvantage. At the first questioning of this hegemonic principle, as happened during the Cold War, the reaction was merciless and the whole world was thrown into an interminable crisis. But without the nuclear power, the dollar would most likely never have become so strong. No country would ever have challenged the U.S. knowing that it could be razed to the ground in a matter of minutes.

Yet, maintaining one’s nuclear power is very expensive: the U.S. government’s Congressional Budget Office estimates nuclear spending at $756 billion over the period 2023-2032, a good $122 billion more than the 2021-2030 period that had already been estimated. Put another way, we are talking about an immense dollar-washing machine on a global scale. And what happens when there are difficulties with the state budget? More is invested in the strategic sector. Wars are money factories. If, however, one cannot make wars frequently, one at least gives the impression of always being close to the outbreak of a conflict, so as to generate a non-stop arms race. Water turns the mill wheel. Simple as that.

Hegemony is based on the political utility of insecurity for a war always around the corner

Indeed, without insecurity as a permanent figure in strategic calculations, nuclear hegemony would not work.

If the logic of provocation prevails, the ground force surrenders the advantage of manoeuvre because it does not develop a counter to a weapon that the adversary possesses, has a doctrine of employment and trains for survivability and resilience. A ground force that cannot manoeuvre can neither conquer terrain nor force objectives. In other words, it cannot win battles. Giving up manoeuvre is a sure path to defeat on the battlefield.

It is hard to believe that large-scale combat operations against a nuclear-armed adversary will not go nuclear if victory is sought. Not going nuclear today may mean not winning. Not winning may not be a viable option in the next big war between states.

Again as reported by the Atlantic Council, the U.S. should move towards an upgrading of nuclear warfare, following three points:

First, the armed forces should use resources to initiate a plan to implement ‘nuclear culture’ among both command plans and troops, so as to raise awareness and normalise to the idea of nuclear war.

A second step is to include adversary nuclear attacks in the scenarios of large-scale conventional combat operations, so the armed forces should organise and lead this training.

Third, military leaders should mandate that acquisition waiver decisions that exempt contractors from meeting nuclear survivability requirements for equipment and vehicle development be the responsibility of the Office of the Secretary of the Army and not delegated. Delegation is likely to result in exemptions being granted for convenience or to reduce costs without a full understanding of the strategic and operational implications of the threat.

Keep in mind that deterrence is partly based on the principle that adversaries are vulnerable. All conceivable situations in which the aggressor’s fear of retaliation will be minimal should be explored and attempts made to eliminate them. Vulnerability should lead states to be more cautious and refrain from even minor provocations because of the fear of escalation and because the gains can only be limited. Neither a completely effective defence nor the abolition of nuclear weapons is possible, but only these could eliminate vulnerability in the nuclear age.

With vulnerability comes uncertainty: one cannot know the exact range, location or timing of the attack. Of further importance is the uncertainty over the ability to control escalation. Since the severity of the consequences of a nuclear war is enormous, even a low probability of unintended escalation is sufficient to induce caution. The very essence of a crisis is its unpredictability and the fact that, once initiated, there is no guarantee that either state can control its development. The enemy is seen as a rational actor and if it acts unpredictably, the risk increases.

In all this, consider that we do not know the actual development of the various types of weaponry, the vanguards and latest prototypes are unknown. This means that the ‘special status’ as a nuclear power on a global scale is a much sought-after label to be able to carry more political weight and dialogue with partners on a more equal footing.

It does not matter whether or not the U.S. has stronger nuclear technologies than others: what matters is the world’s perception of its own country. The threat must appear credible. Communicating credible deterrence is an active process. It is not the static equivalent of the scarecrow in a farmer’s field. It is more like an active farmer patrolling the field with his rifle, firing it from time to time to make sure and prove that it works. The nuclear equivalent is the regular maintenance, training and operation of nuclear forces in realistic geostrategic circumstances.

Here we can see why it suits the U.S. to revive the nuclear danger card: a reputation to maintain, banks to restore and a bit of a show on the silver screen.

Who knows whether this arrogance will not cost America dearly as it seeks to become great again?