Embracing the opportunities hidden in the project of an industrial revolution is a crucial step in choosing what ethical sense to give to the transformations that lie ahead.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

The phase of transition and transformation of markets and global politics, passes through a momentum of change in the world of technology that involves the entire sector of industry and technology. A process that arouses fascination and interest, but also concerns and reflections on the risks of a dystopian and dangerous reality for the subsistence of the human being as the dominant subject on the planet. Already, artificial intelligence is questioning us deeply and is changing the daily lives of billions of people with great speed. Technological progress, a great myth of the 19th century, is one of the most decisive spaces for social and political life. Human evolution cannot be stopped, but it can be directed according to ethics. What is difficult in this period of human history is to discern opportunities from risks, to understand which technologies are actually at the service of the common good and which, instead, are tools of the elites to dominate the masses. A timely reflection is that around the proposal of an ‘industrial revolution 4.0’ promoted by the BRICS+.

Chapter Four: the BRICS come into play

Fourth Industrial Revolution (also known as Industry 4.0). This is not the title of a marketing convention for career CEOs, it is the title of the new programme released by the BRICS to meet the challenges of technological transformation. A historical recourse that punctually presents itself to humanity. We will try to understand it by analysing a paper recently published in the BRICS Journal of Economics.

In the BRICS countries, both the founding ones and the new entrants, the adaptation of industrial policies must be addressed. The revolution already taking place in the world is characterised by extensive digitisation, integrating all physical assets into digital ecosystems, and involving advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence, robotics and the Internet of Things (IoT).

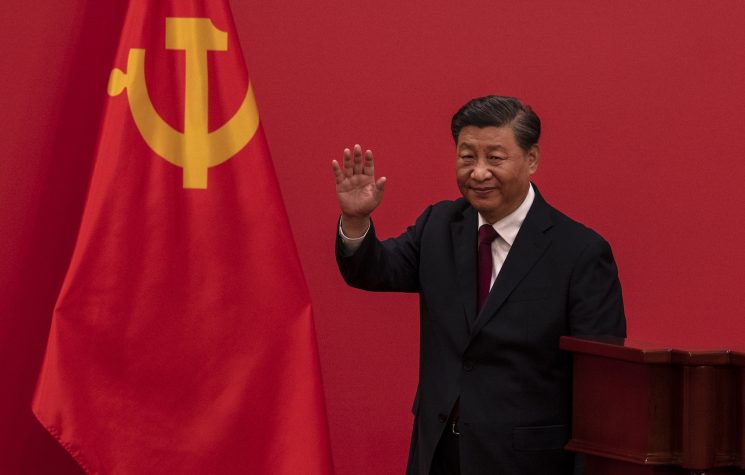

The introduction of these technologies could undermine the traditional competitive advantages of developing countries, which are based on low labour costs. For example, automation and 3D printing may reduce the need to reconfigure supply chains, making BRICS countries less attractive for foreign direct investment (FDI). China, in particular, stands out for its level of automation and innovation, while the other BRICS states risk falling behind.

On the other hand, IoT technologies can improve the competitiveness of LDCs by simplifying communications along supply chains and decreasing dependence on human labour, with the consequence that comparative advantages will no longer be based only on cheap labour, but on the availability of capital and a highly skilled workforce.

The 4.0 revolution, the publication states, will also lead to a reorganisation of global value chains (GVCs), fostering greater specialisation and geographical dispersion of production processes, which, if not adequately compensated for by specialised training or sufficient substitution of machines for human labour, could lead to a reduced availability of skilled workers and insufficient infrastructure, which could hamper their ability to compete with more developed nations.

While Industry 4.0 offers opportunities for growth, it also presents considerable risks for BRICS members, requiring careful planning of industrial policies to take advantage of new technologies and not fall behind in the global economic landscape.

The BRICS and the Networked Readiness Index

Let us talk about indices, a perhaps tedious but indispensable issue for geo-economic analysis. We refer to the Networked Readiness Index (NRI) and an index of future production readiness, both assessing various factors such as technology, governance and human capital.

The BRICS rank mid-table compared to the G7 countries, with lower scores in several key indicators. China emerges as a leader within the partnership, with significant advantages in legislation, Internet access and R&D investment, although it has weaknesses in regulation and environmental pollution. Russia follows, with good performance in clean technologies and quality of education, but faces challenges in regulation and law enforcement. Brazil stands out for its use of clean technologies and the quality of online public services, but suffers from inadequate regulation. South Africa has good e-commerce legislation but suffers from serious inequalities and quality of life problems. Finally, India, although at the bottom of the ranking, has strengths in government e-services, but faces significant challenges such as low Internet connectivity and environmental problems. Data from the new members who joined in 2024 are not yet integrated (but we await that data, which we may integrate in another article).

Analysing the second index, it emerges that the BRICS are at least some way behind the G7 countries in terms of production complexity and institutional conditions. Although China and India have similar strengths in areas such as market size and the contribution of government spending to innovation, both face problems such as low mobile penetration. Russia has advantages in ICT and human capital, but needs to improve its regulation and foreign trade. Brazil is good at investment, while South Africa has a good distribution network, but suffers in terms of human capital and sustainability.

Something is therefore still missing. And it is here that the infamous BRICS-signed Industrial Revolution wants to take its place.

The programmatic points of the Industry 4.0 project

To solve the disadvantages, the partnership has adopted a project that will continue to develop the following points:

- Position of the BRICS

China stands out as the leader, followed by Russia, while the other BRICS show lower performance, with the ICT sector in China and India growing strongly. Although the BRICS contribution to global GDP has doubled in the last two decades (23.5% in 2018), only China is among the world’s top 25 economies in terms of economic complexity (which is different from GDP).

- Challenges and opportunities

The BRICS, with the exception of China, continue to be suppliers of traditional low-value-added goods. Their export growth is mainly related to raw materials. The introduction of Industry 4.0 technologies presents risks of job losses, especially in the mining and agri-food sectors, but also offers opportunities for the development of SMEs and the creation of new sectors.

- Internal differences and technological development

Internal differences between the members of the partnership concern investment activity and human capital. China accumulates technological skills through investment, while the other countries are more dependent on foreign investment, access to digital resources and workforce training, which are essential for their future competitiveness.

- Policies needed

Economic policies need to be revised to meet the challenges of Industry 4.0, which includes strategic trade programmes, a renewed role of the state in the economy, restructuring of business support systems and a series of experimental regulations for emerging technologies, all in tandem with the necessary addressing of regional inequalities, encouraging development in less advanced areas.

The ability of the BRICS to integrate Industry 4.0 technologies will significantly influence their economic growth trajectories and their position in the global market.

A necessary ethical reflection

At a first reading of the Industry 4.0 document, one seems to be faced with a proposal that has something very similar with the Fourth Industrial Revolution promoted by the World Economic Forum, as enunciated by Klaus Schwab, thus globalist and anti-multipolar.

A few points must then be clarified. First of all, technological development is not an evil in itself, it is a part of individual and social human evolution, it has always been present throughout history and it is improbable, as well as physiologically almost impossible, that it should stop. The human being is a creative being. The problem then shifts to another aspect, namely ‘who manages the means of production’, Karl Marx would have said, i.e. for what reason and with what use certain technological revolutions take place: whether they are for the good of the community or whether they are for the interests of a few that overwhelm the many, changes everything. On how to discern what is really the common good and what instead is the good of the few but made to be believed as the common good, we enter another level of ethics, with its rules and mechanisms. However, it is true that the acceleration taking place is difficult to manage and often seems to get out of hand, because it is a globally diffused phenomenon, with different speeds of progress, with different masters. It almost seems as if the situation is constantly getting out of hand. Especially digital technologies appear as inexorably faster and stronger than human action.

The issue of human or technological employment in work also remains open, as it was already in the 19th century: can the machine replace man? More: is it permissible for the machine to replace man?

Here the problem takes two different directions. Firstly, we have been accustomed to seeing work as an indispensable element of human life, but with modernity it has become the trap of man, who now finds himself a slave to it. The model of today’s successful man is the one who makes money work for himself, not work for money; it is the rich person who can afford not to work, exactly as he was centuries ago and as he never ceased to be. Yet, work has been extolled as the path to emancipation and fulfilment of human life, both individually in capitalism and collectively in socialism. Probably – let us launch a provocation – the current transformations force us to rethink the centrality of work. What kind of society would we have if, instead of work, at the centre were hobbies, or the realisation of one’s dreams and projects, or happiness instead of wages? These are deliberately provocative, but necessary questions, because the de-anthropisation of work, with the substitution of technology, actually pushes humanity towards a kind of ‘liberation’ from the work game. And once liberated, one either remains truly free, or risks becoming a slave to something else.

The second direction is one that can turn this process into a trap, opening up to a dystopian world in which humanity falls into an Orwellian slavery, where resistance is a kind of Luddism necessary to survive. Or, a possible reform of the coexistence of man and technology, a process that is already underway and still requires serious and decisive reflection, leading to educational processes to prepare future generations to be ready, not late.

An industrial revolution such as the one planned by the BRICS is also to be seen in the strategic – hence exquisitely geopolitical – logic of standing up to the Western adversary. Victory, in the geo-economic sphere, is not won in the short term. Without adequate preparation and perseverance in reform policies, there is a risk of failure of the BRICS project itself.

Embracing the opportunities hidden in the project of an industrial revolution is a crucial step in choosing what ethical sense to give to the transformations that lie ahead.