The thinking and actions of Nasser’s government inspired a wave of nationalist movements in the Middle East and North Africa in the 1950s and 1960s, most of them directly supported by the Egyptian leader.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

“I clearly saw that the entire Arab zone constituted, in fact, a single unit and that we should not keep it separate and divided into different sections” (Gamal Abdel Nasser)

You can also read: Gamal Abdel Nasser and the struggle for Egyptian independence, by the same author

Imbued with a revolutionary feeling that was still extremely confused, with the crisis triggered by the beginning of the Second World War, Gamal Abdel Nasser found himself tempted to use “political assassination as the only concrete action capable of saving the country”, as he himself admitted. He and his supporters intended to assassinate King Faruk and his family. For some of the crimes, there was action planning and weapons preparation, with secret meetings. After an abortive attack, he realized that this path would not lead to the overthrow of the regime and social transformation.

The end of the War without the recognition of independence was a lesson to Nasser and his companions in the secret movement. But perhaps the main factor that changed once and for all their vision of revolution was the Arab-Israeli War of 1948. As soon as imperialism decided to partition Palestine, in September 1947, they got together and decided to militarily help the Palestinian people.

Nasser fought in the war and from the defeat of the Arab countries he learned a decisive lesson, which guided his thinking and policies until his death:

“After the siege and the fighting, upon returning to his homeland, I clearly saw that the entire Arab zone constituted, in fact, a single unit and that we should not keep it separate and divided into different sections. The evolution of events reinforced my conviction that Cairo, Amman, Beirut and Damascus constituted a single area, which suffered the same events, and which have the same obstacles to overcome: imperialism.

Israel is nothing more than a creation of imperialism. If Great Britain had not had a mandate over Palestine, the Zionists would never have found the necessary support to realize the idea of a national home. That ideal would have remained a ridiculous and unrealizable vision.”

This thought took hold in a large part of the Egyptian army, which was expressed in the election of the Military Club in 1951. The Free Officers Movement, which began as a small group, became a real force, made up of officers from the high and middle echelon. Anti-imperialist sentiment against the British occupation also spread devastatingly among broad sectors of the country’s population.

The Revolution of 1952

The Egyptian people were exhausted from the imperialist exploitation that caused misery and suffering, while Faruk lavished luxury and monopolies extracted all the country’s wealth. Outrage exploded over the murder of 50 soldiers by British forces in the city of Ismailia, which the people saw as a symbol of imperialist oppression over Egypt. On January 26 and 27, 1952, the streets of Cairo and other cities were taken over by popular anger, which destroyed 750 establishments, with an emphasis on British properties or places frequented by British people.

The situation became increasingly critical for the regime. However, despite Egypt’s relative modernization, the country was still basically feudal, in which the great mass of workers lived in the countryside and, therefore, was politically backward (although, by the way, conflicts in the countryside became more intense). The workers were disorganized and there was no political leadership. It was left to the Free Officers, many of whom had connections with the social reality of the people, to lead the insurrection.

In the early hours of July 23, tanks commanded by the Executive Council of the Revolution, composed of nine members (including Nasser), organized by the Free Officers, surrounded the royal palace of Abdin and deposed Faruk, soon expelling the British occupants. It was the end of 30 years of puppet monarchy and 70 years of military rule by England.

“The most impressive thing about the Revolution of July 23, 1952, is that the Armed Forces, who rose up to stage it, were not its creators, but merely instruments of the popular will”, Nasser said. “[…] It was not the army that determined its role in the events. The opposite would be closer to the truth. The events and their evolution, this is what decided the role of the army, in the formidable fight for the liberation of the country.”

Faced with the political disorganization of the revolution, its guiding principles were extracted from the aspirations and needs of the popular struggle: 1) destruction of colonialism and Egyptian traitors and their agents; 2) liquidation of feudalism; 3) end of the monopoly and domination of capital over the government; 4) establishment of social justice; 5) formation of the powerful national army; 6) establishment of a solid democratic system.

Although disorganized because it did not have a revolutionary workers’ leadership, the popular movement was active and played a key role in the revolution. With the overthrow of the old regime, unions were strengthened (despite being controlled by the nationalist movement), agricultural cooperatives were created in the countryside and the land was divided into countless small individual properties. Workers imposed a regime of greater democracy in labor administration, achieving salary increases and a reduction in working hours to 7 hours a day.

Gamal Abdel Nasser nationalized foreign monopolies, nationalized British and French capital, as well as the means of production that he placed under the public domain (railways, ports, airports, highways, dams, electricity, banks, etc.). The public sector also began to hegemonize industry and control most commerce.

In relation to most social revolutions in history, the Egyptian one experienced almost no violence, civil war or imperialist intervention. Imperialism tried to start a counter-revolution in 1954, instigating a revolt by cavalry officers, which was promptly controlled by the government.

Nasser’s greatest challenge, however, came in 1956. Upon finding itself boycotted by the imperialist powers to finance the construction of the Assuan dam (which would make ⅓ of the country’s land cultivable), the Egyptian government decided to nationalize the Suez Canal, administered by a Franco-British company. In a combined maneuver, Israel invaded Egypt, which halted the Zionist advance. France and England offered to intervene, but Nasser refused, which led to the powers bombing strategic points in the country. Finally, the UN intervened diplomatically, with Soviet support for Cairo, withdrawing foreign troops from Egypt.

The beginning and end of the Arab Nation under Nasserism

Although he declared himself a socialist (like many nationalist movements around the world), Nasser believed that socialism was sufficiency, justice and social freedom and that private property should be protected. As a radical petit-bourgeois nationalism, the country’s economy, in the late 1960s, became 90% controlled by the state bureaucracy.

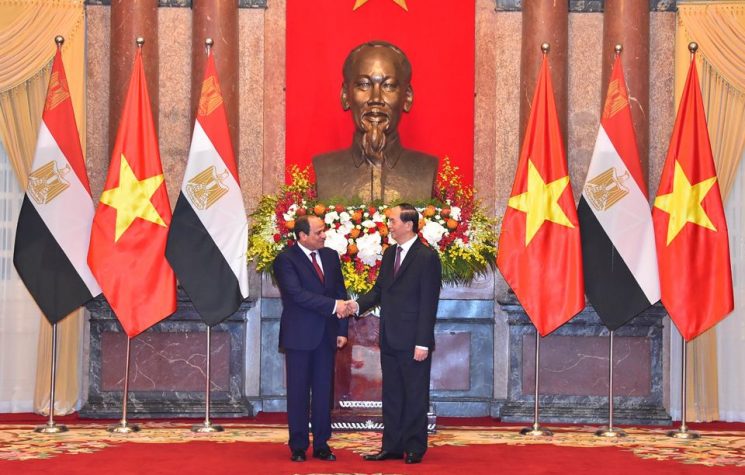

The thinking and actions of Nasser’s government inspired a wave of nationalist movements in the Middle East and North Africa in the 1950s and 1960s, most of them directly supported by the Egyptian leader. As a way of starting the implementation of the Arab Nation project, Egypt and the Ba’ath Party government in Syria signed a commitment that led to the union of the two countries into a single state: the United Arab Republic, in 1958. The formation of UAR encouraged nationalist sectors in several Arab countries, which led Anglo-American imperialism to intervene militarily in Lebanon, Iraq and Jordan to prevent the nationalists from taking power.

The Middle East has always been an extremely important point for imperialist rule, due to its geostrategic position and oil. At that time, around half of the world’s oil reserves were found in that region, where major oil companies such as Shell, Standard Oil and Rockefeller already operated.

The Arab nationalism promoted by Nasser, although he tried to reconcile with imperialism (being neutral in the “cold war” and flirting on several occasions with the USA), represented an obstacle to domination in the Middle East. The governments of Iraq, Iran and North Yemen were also influenced by the Egyptian Revolution in the 1950s and the UAR threatened to expand. It was then that, in 1961, a coup supported by imperialism overthrew the Syrian government and removed the country from the Union, which was made up only of Egypt, until 1971.

One of Nasser’s last attempts to combat imperialism militarily and unite the Arab peoples was the Six-Day War of 1967, when Egypt, Jordan and Syria blockaded Israel commercially and militarily. Israel then started the war and annexed part of the Sinai desert and destroyed much of Egypt’s military power. The defeat of the Arab countries severely undermined the prestige of Nasser and Arab nationalism and led to the emergence, instigated by the USA, of political Islam as a counterpoint to nationalism and communism.

Nasser died in September 1970, victim of a heart collapse, at the age of 52. The vice president since 1969 and former member of the Free Officers, Anwar el-Sadat, took over in his place and discreetly began rapprochement with Israel and the USA. In 1971, Sadat approved a new right-wing constitution and began a process of privatization for national and foreign capital.

Sadat repressed, in 1974, the most radical movement of students and workers and, in 1977, he was almost overthrown by a popular uprising against the increase in the price of bread. The following year, the capitulation reached its peak when Egypt became the first Arab country to recognize the State of Israel. In 1981, Sadat was assassinated, being succeeded by Osni Mubarak, who ruled Egypt until 2011, being one of the main allies of imperialism in the Arab World.