Although many Nazis were brought to book for their crimes, no British were, Declan Hayes writes.

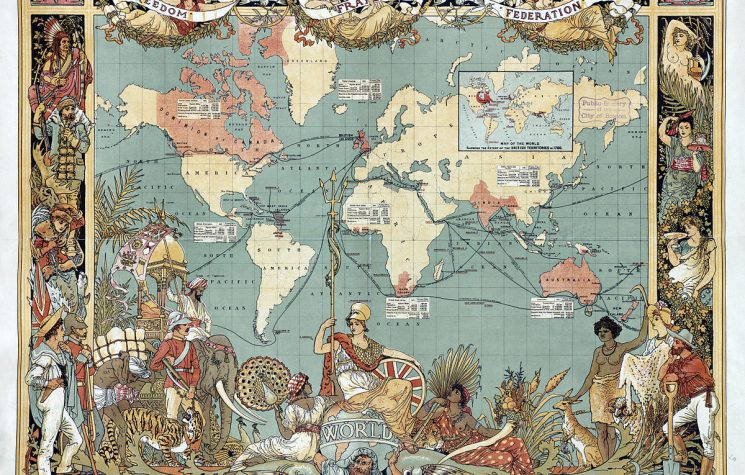

Caroline Elkins’ accounts of British soldiers ramming broken bottles into the vaginas of female Kenyan prisoners during the Kikuyus’ Mau Mau revolt is not, by any stretch, the worst example of Albion’s imperial violence she recounts. Because this 870 page book is awash with similar instances of systematic war crimes by the British administration in Kenya, in Nigeria, Jamaica, South Africa, Malaya, Palestine, Cyprus, Nyasaland, India and countless other outposts of empire, justifiable comparisons between the British and the Nazis arise time and again.

And, although many Nazis were brought to book for their crimes, no British were, even though General Sir Frank Kitson, one of the most notorious of these Grade A war criminals, who hopscotched about from one colonial killing field to the next, is still alive and, no doubt, still plotting the murder of others. The book makes it plain that the British had a bunch of such military and civil service troubleshooters, psychopathic thugs like Kitson and Bomber Harris they were prepared to send, almost at a moment’s notice, to any part of their rotten empire where the “natives” had to be duffed up, a euphemism for barbaric tortures derived from Douglas Duff, one of their Satanic number.

Many of these savages, such as Percival and Montgomery, served alongside the Black and Tan terrorist group in Ireland, before moving on to Palestine, India and Malaya where they honed their torture techniques, which resembled those devils use in medieval paintings.

Gruesome as her descriptions of that savagery is, the book’s strongest point is that it gives us the oxymoronic prism of liberal imperialism to ruminate on these crimes of empire and the savages who committed them, who colluded in them and who covered them up both judicially and with the pomp and circumstance of empire.

Elkins stresses that Queen Victoria’s Silver Jubilee was, much like the 1952 coronation of the young Queen Elizabeth, used to bamboozle her subjects with the majesty of empire and to convince those cretins they were part of the much bigger and nobler project of Making Britain Great Again. Queen Elizabeth 11 spelt out the method by which the Great was to be put back in Britain when she declared, on her first prorogation of Parliament, that her thugs had murder by the throat in Malaya by the use of terror tactics they had honed in Palestine. Although the media lionized Gerald Templer, Templer of Malaya as they christened the Queen’s chief war criminal in Malaya, it is worth noting, with respect to Wikileaks and her forces’ more recent war crimes, that only the Communists’ Daily Worker newspaper asked any probing questions about Malayan war crimes and that Templer and his fellow thugs gave them short shrift.

Elkins alleges on page 649 that the main reason MI5 ‘fessed up to their Mau Mau war crimes was because Julian Assange, whom they now hold in their most secure dungeon, was going to release a trove of papers exposing their horrendous war crimes against the Kikuyu in Kenya. She also shows, with examples from Malaya, India, Palestine and elsewhere, that Assange was far from the first instance of these colonial thugs shooting, torturing or just plain murdering the messenger.

The book’s pre-eminent strength is in showing how such propaganda and censorship were both central to Britain’s genocide campaigns and to these criminals self fashioning themselves, like their current American partners in crime do, as the standard bearers of progress and enlightenment.

It was to whitewash those crimes and to confer some faux dignity on Albion’s empire of concentration camps and gulags that Rudyard Kipling, George Orwell’s “prophet of British imperialism” was given the 1907 Nobel Prize for Literature. Kipling was part of a gigantic propaganda fig leaf that hid the oxymoron of liberal imperialism, the velvet glove that sheathed a merciless fist that crushed, castrated and enslaved Albion’s new-caught, sullen peoples who were half devil and half child.

Elkins makes it plain as day there was no sparing the rod when “our boys” held it over these half-children, that uprisings in India, Palestine and Jamaica were brutally suppressed by Tommies, who revelled in cutting the genitals off their prisoners and sticking them down their throats. Although their genocide of the Boers is well-known (by those who want to know), less known is that over £6 million was raised for wounded Tommies, and a mere £6,500 for Afrikaner women and children those same Tommies were starving to death in concentration camps that were as bad as Hitler’s. Think of that when you watch youtube’s homecoming videos of American service personnel returning Stateside after doing their own little Mỹ Lais and Abu Ghraibs.

Although Elkins makes the excellent point that Irish collaborators were central to all of these crimes in India, in Malaya, in Palestine and in South Africa, she also claims that the Irish Times was “long a thorn in Britain’s imperial side”. The Irish Times is, in fact as much a defender of liberal imperialism as is NATO’s most hawkish British or American media outlets.

Her knowledge of the so-called Irish War of Independence, the (Black and) Tan War, as we purists call it, is likewise flaky. It was the solid, unwavering Sinn Féin vote for independence that the British feared and not the IRA’s campaign that warranted barely a footnote in any of the British Army regimental histories and that Montgomery dismissed a light training exercise. Nor did the IRA get their tactics from the Boers who were excellent horsemen and marksmen but rather, theirs was a hotchpotch, aided by some talented bomb makers like Jim O’Donovan. And, though it is heartening to know that Dan Breen’s My Fight for Irish Freedom was a best seller in Hindi, Punjabi and Tamil, the reason for that and for why the great General Võ Nguyên Giáp had his own dog-eared copy was there was little other relevant literature about. Though Breen was no Giáp and Tom Barry was no Chairman Mao, they made their own modest contributions to the theory and practice of guerilla warfare, which need not detain us here, except to say that Elkins, no more than anyone else, can be experts on all things.

Elkins’ very considerable contribution is not on such localized detail. Rather, she has given us an edifice, a petard, a gallows I would hope, on which to hoist those British and American criminals, who move heaven and earth to persecute Julian Assange, even as the Biden, Blair, Bush, Clinton and Obama organized crime families swan about leaving a slug’s trail of misery and slime on whatever they touch.

We have, on Facebook and similar social media outlets, beautiful young Syrian, Yemeni and Palestinian children asking, in their innocence, for NATO to stop throttling them. And then we have the bigger battalions, who are as impervious to today’s crimes of empire in Syria, Yemen and Palestine, as their colonial forefathers were to similar crimes in those very same theaters. I know whose side I am on.

Legacy of Violence: A History of the British Empire, Caroline Elkins, The Bodley Head.