Efforts by the U.S. and NATO to draw Africa into their geopolitical conflicts raise serious concerns, writes Vijay Prashad.

By Vijay PRASHAD

On Oct. 17, the head of U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM), U.S. Marine Corps General Michael Langley visited Morocco. Langley met with senior Moroccan military leaders, including Inspector General of the Moroccan Armed Forces Belkhir El Farouk.

Since 2004, AFRICOM has held its “largest and premier annual exercise,” African Lion, partly on Moroccan soil. This past June, 10 countries participated in the African Lion 2022, with observers from Israel (for the first time) and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

Salah Elmur, Sudan, “The Green Room,” 2019.

Langley’s visit is part of a broader U.S. push onto the African continent, which we documented in our dossier No. 42 (July 2021), “Defending Our Sovereignty: U.S. Military Bases in Africa and the Future of African Unity,” a joint publication with The Socialist Movement of Ghana’s Research Group.

In that text, we wrote that the two important principles of Pan-Africanism are political unity and territorial sovereignty and argued that the “enduring presence of foreign military bases not only symbolises the lack of unity and sovereignty; it also equally enforces the fragmentation and subordination of the continent’s peoples and governments.”

In August, U.S. Ambassador to the U.N. Linda Thomas-Greenfield travelled to Ghana, Uganda and Cape Verde. “We’re not asking Africans to make any choices between the United States and Russia,” she said ahead of her visit, but, she added, “for me, that choice would be simple.”

That choice is nonetheless being impelled by the U.S. Congress as it deliberates the Countering Malign Russian Activities in Africa Act, a bill that would sanction African states if they do business with Russia (and could possibly extend to China in the future).

To understand this unfolding situation, our friends at No Cold War have prepared their briefing No. 5, “NATO Claims Africa as Its ‘Southern Neighbourhood,’” which looks at how NATO has begun to develop a proprietary view of Africa and how the U.S. government considers Africa to be a frontline in its Global Monroe Doctrine. That briefing can be downloaded here.

In August 2022, the United States published a new foreign policy strategy aimed at Africa. The 17-page document featured 10 mentions of China and Russia combined, including a pledge to “counter harmful activities by the [People’s Republic of China], Russia, and other foreign actors” on the continent, but did not once mention the term “sovereignty.”

Although U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken has stated that Washington “will not dictate Africa’s choices,” African governments have reported facing “patronising bullying” from NATO member states to take their side in the war in Ukraine. As global tensions rise, the U.S. and its allies have signalled that they view the continent as a battleground to wage their New Cold War against China and Russia.

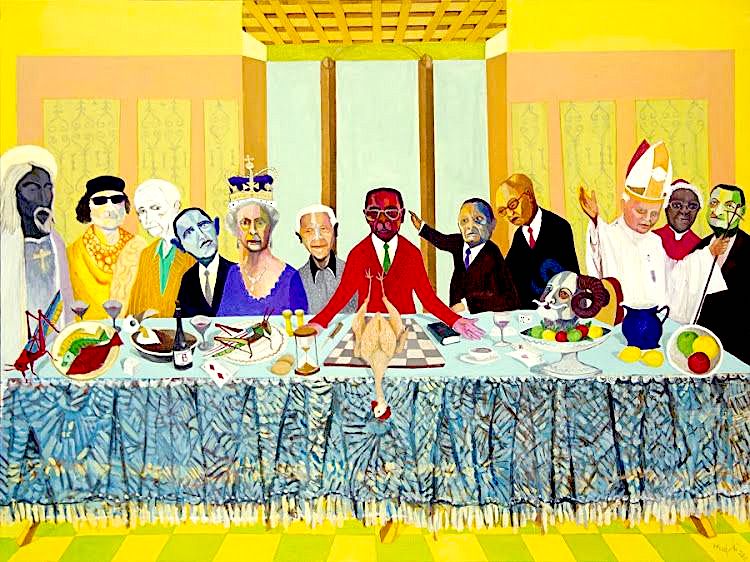

Richard Mudariki, Zimbabwe, “The Passover,” 2011.

A New Monroe Doctrine?

At its annual summit in June, NATO named Africa along with the Middle East “NATO’s southern neighbourhood.” On top of this, NATO’s Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg ominously referred to “Russia and China’s increasing influence in our southern neighbourhood” as a “challenge.”

The following month, the outgoing commander of AFRICOM, General Stephen J. Townsend, referred to Africa as “NATO’s southern flank.”

These comments are disturbingly reminiscent of the neocolonial attitude espoused by the Monroe Doctrine of 1823, in which the U.S. claimed Latin America as its “backyard.”

This paternalistic view of Africa appears to be widely held in Washington. In April, the U.S. House of Representatives overwhelmingly passed the Countering Malign Russian Influence Activities in Africa Act by a vote of 415-9.

The bill, which aims to punish African governments for not aligning with U.S. foreign policy on Russia, has been widely condemned across the continent for disrespecting the sovereignty of African nations, with South African Foreign Minister Naledi Pandor calling it “absolutely disgraceful.”

The efforts by the U.S. and Western countries to draw Africa into their geopolitical conflicts raise serious concerns: namely, will the U.S. and NATO weaponise their vast military presence on the continent to achieve their aims?

Amani Bodo, DRC, “Masque à gaz” or “Gas Mask,” 2020.

AFRICOM: Protecting US & NATO Hegemony

In 2007, the United States established its Africa Command (AFRICOM) “in response to our expanding partnerships and interests in Africa.” In just 15 years, AFRICOM has established at least 29 military bases on the continent as part of an extensive network which includes more than 60 outposts and access points in at least 34 countries – over 60 percent of the nations on the continent.

Despite Washington’s rhetoric of promoting democracy and human rights in Africa, in reality, AFRICOM aims to secure U.S. hegemony over the continent. AFRICOM’s stated objectives include “protecting U.S. interests” and “maintaining superiority over competitors” in Africa. In fact, the creation of AFRICOM was motivated by the concerns of “those alarmed by China’s expanding presence and influence in the region.”

From the outset, NATO was involved in the endeavour, with the original proposal put forward by then Supreme Allied Commander of NATO James L. Jones, Jr. On an annual basis, AFRICOM conducts training exercises focused on enhancing the “interoperability” between African militaries and “U.S. and NATO special operations forces.”

The destructive nature of the U.S. and NATO’s military presence in Africa was exemplified in 2011 when – ignoring the African Union’s opposition – the U.S. and NATO launched their catastrophic military intervention in Libya to remove the government of Muammar Gaddafi.

This regime-change war destroyed the country, which had previously scored the highest among African nations on the U.N. Human Development Index. Over a decade later, the principal achievements of the intervention in Libya have been the return of slave markets to the country, the entry of thousands of foreign fighters and unending violence.

In the future, will the U.S. and NATO invoke the “malign influence” of China and Russia as a justification for military interventions and regime change in Africa?

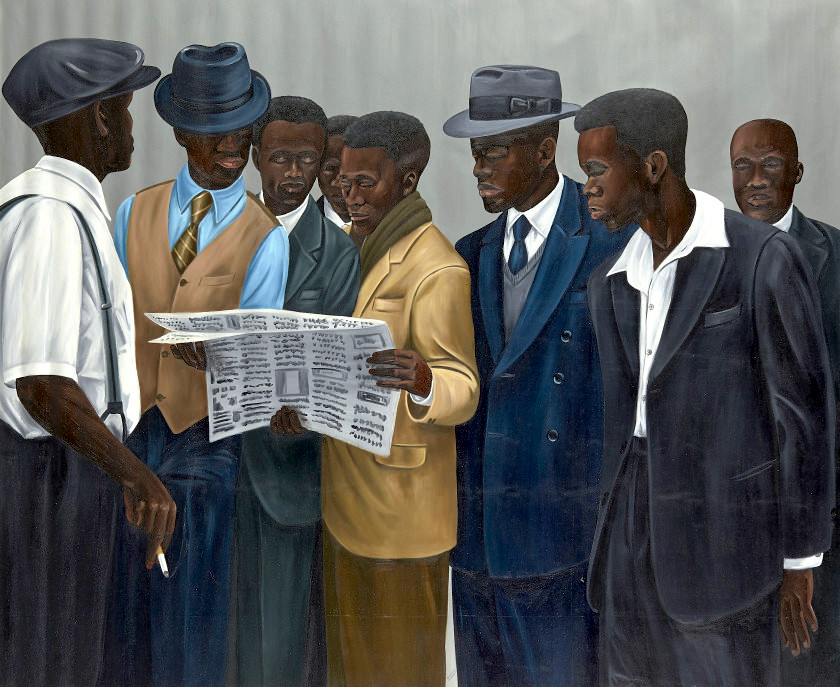

Zemba Luzamba, DRC, “Parlementaires debout” or “Parliamentarians Standing,” 2019.

Africa Rejects a New Cold War

At this year’s U.N. General Assembly, the African Union firmly rejected the coercive efforts of the U.S. and Western countries to use the continent as a pawn in their geopolitical agenda. “Africa has suffered enough of the burden of history,” said Chairman of the African Union and President of Senegal Macky Sall;

“it does not want to be the breeding ground of a new Cold War, but rather a pole of stability and opportunity open to all its partners, on a mutually beneficial basis.”

Indeed, the drive for war offers nothing to the peoples of Africa in their pursuit of peace, climate change adaptation and development.

At the inauguration of the European Diplomatic Academy on Oct. 13, the European Union’s chief diplomat, Josep Borrell, said, “Europe is a garden… The rest of the world… is a jungle, and the jungle could invade the garden.” As if the metaphor were not clear enough, he added, “Europeans have to be much more engaged with the rest of the world. Otherwise, the rest of the world will invade us.”

Borrell’s racist comments were pilloried on social media and eviscerated in the European Parliament by Marc Botenga of the Belgian Workers’ Party. A petition by the Democracy in Europe Movement (DiEM25) calling for Borrell’s resignation has received over 10,000 signatures.

Borrell’s lack of historical knowledge is significant: it is Europe and North America that continue to invade the African continent, and it is those military and economic invasions that cause African people migrate. As Sall said, Africa does not want to be a “breeding ground of a new Cold War,” but a sovereign place of dignity.

Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research via consortiumnews.com