By Todd MILLER

In December 2019, the city of Chula Vista announced with much fanfare that it had been designated as California’s first Welcoming City. This designation honored the community’s commitment to include its undocumented residents. Located 15 minutes from the U.S.-Mexico border, Chula Vista has one of the highest populations of immigrants in the United States, about 30 percent of its population of 270,000. Rachel Peric, the director of Welcoming America, said this “inclusive environment” was a “model . . . to ensure residents of all backgrounds—including immigrants, can thrive and belong.”

College student Nicholas Paúl told me his city’s designation “was a proud moment” for his community. Raised on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border, Paúl is emblematic of many residents from Chula Vista. “I’m a fronterizo,” he told me. Every weekend he crossed the border to Tijuana to visit family and friends. “It’s a way of life,” he said. “It’s not something that is unique to me. It’s my whole family, my whole neighborhood.”

So it came as a shock to Paúl a year later, in December 2020, when an exposé by San Diego’s daily newspaper revealed that the Chula Vista Police Department was sharing information from automated license plate readers with U.S. Customs and Border Protection, the parent agency of the Border Patrol, and of Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

“They collect information not only about license plates but also the car—make, model, color, location coordinates,” Paúl said. Police mounted cameras on four patrol vehicles that constantly take pictures of license plates while they roam the city. Paúl and other Chula Vista residents feared that they were targeting the city’s undocumented population, possibly his very neighbors. Furthermore, the license plate reading program had been in effect since 2017, so this was happening even as Chula Vista received its Welcoming City designation.

Paúl’s testimony is in a new report, Smart Borders or a Humane World?, that I coauthored with immigrant rights organizer Mizue Aizeki, and border scholars Geoffrey Boyce, Joseph Nevins, and Miriam Ticktin for the nonprofit Immigrant Defense Project and the Transnational Institute.

In this report, we examine what a “smart” border is, especially the version bristling with surveillance and detection technologies currently championed by the Biden administration. Even as the events in Chula Vista spurred border residents, like Paúl, to join forces against invasive license plate reader technology in their community, border technologies are being presented nationally as harmless and humane, especially in comparison to the foreboding physical barrier that dominated the news during the Donald Trump years. The border will be “managed,” in the language of the Biden administration, and it will be as modern and cool as the smartphone in your pocket.

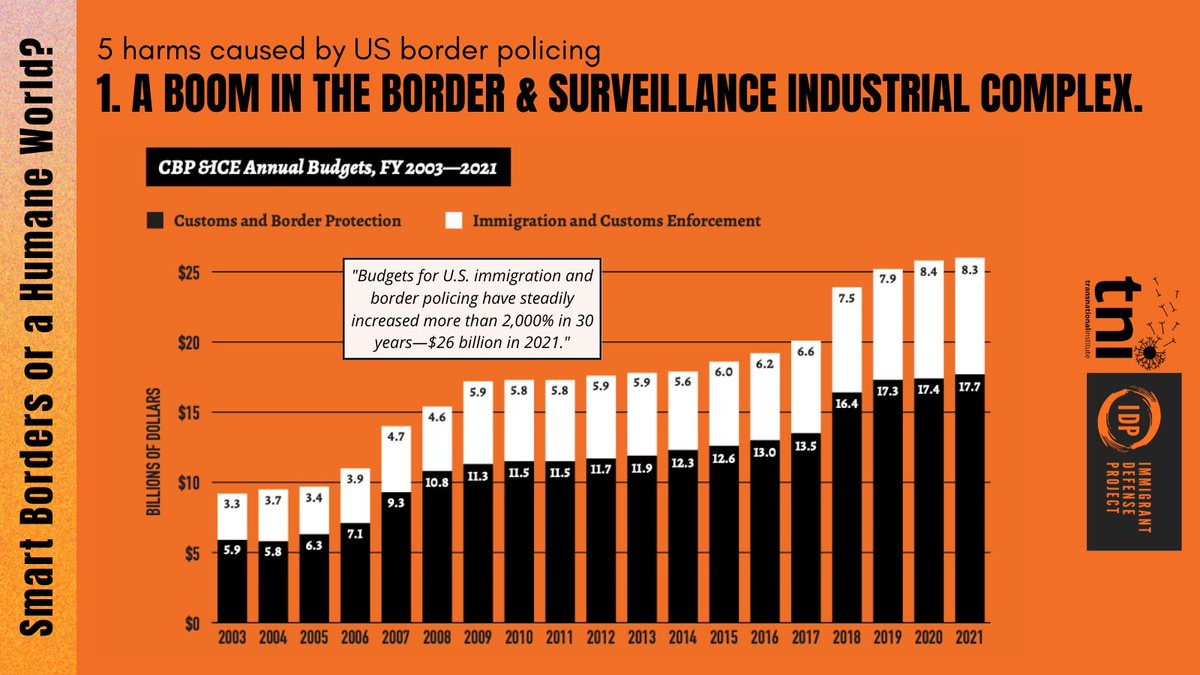

Former representative Nina Lowey (D-NY) expressed this technophilic framing perfectly in July 2020 after the House Appropriations Committee released its 2021 fiscal year draft. The budget, she said, provided “strong investments in modern, effective technologies” for border security while prohibiting funding for “President Trump’s racist border wall boondoggle.” In a way, this is the Democratic version of “border theater,” a smoke-and-mirrors routine that presents “smart” technology as an alternative to the border wall, rather than as an integral part, extension, and perpetuation of it.

The border wall is more than just a physical barrier; it is also a system of video surveillance systems, unmanned aerial systems (or drones), and license plate readers, like the ones used in Chula Vista, which are part of a broadening biometric collection strategy. Biometric collection has grown “big time” for CBP since 9/11, said Patrick Nemeth, the Department of Homeland Security’s director of identity operations, at the 2017 Border Security Expo, the industry trade show for new border technologies, held in in San Antonio, Texas. Nemeth said that CBP’s fingerprint data increased from 10 million to 212 million since 9/11. He boasted that DHS now had the second-largest biometric system in the world, “right behind India’s.” Since then, the number of “unique identity records” collected by the agency has increased to 260 million. And this will only keep growing as CBP upgrades its biometric system to Homeland Advanced Recognition Technology, which not only has facial, iris, and digital fingerprint capability, but will also be able to get a person’s DNA (which is already happening) and track an individual’s “relationship patterns.”

And if you were wondering what the future might entail, drone surveillance technology and biometrics are both melding and advancing together. In April 2018, DHS tested a small drone that can “fly unnoticed by human hearing and sight” along a “predetermined route observing and reporting unusual activity and identifying faces and vehicles . . . comparing them to profile pictures and license plate data.”

Technology evolves so quickly—and with so little transparency—that many border residents are unaware of how intensely their communities are being surveilled. After the exposé, Chula Vista residents like Paúl joined with the American Friends Service Committee and others to form the Chula Vista Surveillance Ad-Hoc Committee. They began to study the issue and planned to pressure City Council members at an April meeting. One obstacle, however, is that “there is a tolerance for this that has to do with society’s being much more used to using technology in a way that’s convenient for them, like using fingerprints or iris scans to open up their phones,” said Pedro Rios, the director of the U.S.-Mexico Border Program for the American Friends Service Committee.

Rios added that the “larger trend of using technology for security monitoring is for me one that is concerning because it could have a significant impact on our civil liberties.”

Chula Vista residents, Paúl and Rios explained, want to know how the Police Department could share data with immigration agencies for three years, since the city signed a contract with the private company Vigilant Solutions in 2017 to provide the Automated License Plate Reader system. When asked by reporter Gustavo Solis, Francisco Estrada, the chief of staff for Chula Vista mayor Mary Casillas Salas, acknowledged that the city chose to share information with the immigration agencies. “ICE and CBP are important,” Estrada said, “because crimes and criminals cross the border and while we do not share information about a person’s immigration status, we do work with federal law enforcement on drug interdiction, human trafficking, stolen vehicles and other crimes.” Thanks to community pressure after the exposé in December, the Police Department announced that it would stop sharing the data with CBP and ICE. Rios told me, however, that the license plate information could still be shared indirectly through “fusion centers,” intelligence hubs that DHS has throughout the country. The Chula Vista Police Department also receives funds from Operation Stonegarden, a DHS grant that funds police in primarily border states to coordinate with CBP.

The organizing committee wanted the city to get rid of the ALPR system altogether. But instead the City Council voted unanimously to keep the program, illustrating a fundamental point we make in Smart Borders or Humane World?: government officials tend to double down on surveillance instead of considering any sort of policy alternative. Casillas Salas, for example, claimed that the anti-surveillance committee was misrepresenting “what the license plate reader is or is not.” It is a tool, she claimed, to fight crime. “We will continue the dialogue, but right now I do not want to take one tool away from our police officers, not one.”

As you’ll discover in this new report, policy makers and elected officials have long asked the wrong questions and gotten the wrong answers about the border and border policing. This is especially true in a world with mounting global crises in public health, climate change, and endemic global inequalities, crises that often trigger migration. Rather than more “smart” technology, we need to “invest in the construction of a just, compassionate, and sustainable world,” as we argue in the report. Instead of asking, What is the best way to secure the border?, we need to ask better questions: How do we help create conditions that allow people to stay in the places they call home, and thrive where they reside? And, when people do have to move, how can we ensure they are able to do so safely?

And maybe even more importantly, What is the world we want to live in, and how do we get there? Part of the answer can be found in what it means to be a Welcoming City: to build a place where all residents, regardless of their immigration status, can thrive and belong.