Canada could play the role of intermediary and diplomatic bridge both for the benefit of its own citizens and the wellbeing of the world as a whole, Matt Ehret writes.

The arctic remains the world’s last frontier of human exploration. It is also a domain of great potential cooperation among great civilizations, or inversely a domain of militarism and confrontation.

In recent years, Russia and China have increasingly harmonized their foreign policies around the Framework unveiled by President Xi Jinping in 2013 dubbed the Belt and Road Initiative. Since its unveiling, this megaproject has grown in leaps and bounds winning over 136 nations, accruing $3.7 trillion of investment capital and evolving new components such as the “Digital Silk Road”, “Health Silk Road”, “Space Silk Road”, and of course the “Polar Silk Road”. In March 2021, the Polar Silk Road, first announced in 2018, was given a prominent role in the 2021-2025 Five Year Plan with a focus on Arctic shipping, resource development, scientific Arctic research and conservation.

With the enthusiastic support of Russia, China has increasingly become a leading force in icebreaker technology, northern resource development, arctic infrastructure construction, with an aim to be a world leader in shipping across the rapidly melting Northwest Passage cutting between 10-15 days off of goods moving between Asia and Europe. The recent clogging of the Suez Canal and over congested Straits of Malacca have been stark reminders that Arctic shipping is a domain of global strategic significance during the 21st century.

Russia’s role as Chair of the Arctic Council between 2021-2023 will also put a major spotlight on the evolving Russia-China paradigm for win-win cooperation of the north as a territory of dialogue and development which is the theme of the upcoming St. Petersburg Arctic Summit later this year.

The Threat of Confrontation Heats Up

Despite these positive strides, many geopoliticans in the west have repeatedly attacked such developments as “efforts to conquer the world and replace the USA as global hegemons”. Those promoting this Hobbesian outlook not only choose to ignore the countless olive branches offered to the west by the Eurasian powers for mutual development, but have also accelerated a policy which some have dubbed a ‘Full Spectrum Dominance’ ballistic missile encirclement of both Russia and China. This latter policy was recently called out by Foreign Minister Lavrov on April 1, 2021 who said:

“We now have a missile defence area in Europe. Nobody is saying that this is against Iran now. This is clearly being positioned as a global project designed to contain Russia and China. The same processes are underway in the Asia-Pacific region. No one is trying to pretend that this is being done against North Korea… This is a global system designed to back U.S. claims to absolute dominance, including in the military-strategic and nuclear spheres.”

Instead of acknowledging the fact that Russian and Chinese military strategies are defensive in nature, advocates of full spectrum dominance have chosen to push an opposing narrative painting both Eurasian nations as competitors and rivals with ghoulish secret intentions to annex the world. Under this confrontational paradigm, both NORAD and NORTHCOM continental defense systems are undergoing a reform under General Glan van Herck who stated in his Declassified Executive Summary of NORAD’s New Strategic Vision:

“Both Russia and China are increasing their activity in the Arctic. Russia’s fielding of advanced, long-range cruise missiles capable of being launched from Russian territory and flying through the northern approaches and seeking to strike targets in the United States and Canada has emerged as the dominant military threat in the Arctic.”

Why the general believes this to be the dominant cause of military threats rather than the USA’s unilateral withdrawal from all confidence building measures such as the 1972 ABM Treaty, the 1987 INF Treaty and Open Skies Treaty is beyond the capacity of this writer’s imagination.

An important part of this continental reform involves an upgrading and expansion of the U.S.-directed Ground Based Midcourse Defense system of 44 silo-based interceptors located in Alaska and California with an additional 20 in response to both China and Russia’s development of hypersonic, maneuverable warheads as well as a new generation of submarine and land-based ICBMs. Former Assistant Secretary of Defense Philip Coyle recently attacked this upgraded GMD program by stating not only is the system woefully inept (only half of its 18 tests since 1999 hit their targets), but is also unnecessarily provocative, forcing Russia and China to upgrade their own systems in response to a threat that never should have existed in the first place. In a 2019 interview Coyle stated:

“All of this is causing Russia and increasingly China to build more and more offensive systems, so that they can overwhelm U.S. missile defence- assuming that they would work… We have no way of dealing with more and more missiles from Russia or China and so building up more and more missile defense is backfiring”.

General van Herck has also championed Artificial Intelligence and machine learning technology across all domains of data collection and even supplementing human decision making as part of the goal of achieving “global integration, all domain awareness, information dominance to reach decision superiority”. Dubbed Pathfinder, van Herck has stated “I absolutely believe it can be a model for the Department of Defense. It lays the foundation for improved data-driven decision making and enhanced capability”. Whether it is wise to strive to cut decision making on matters such as thermonuclear war down to 12 minutes as is currently celebrated by Pathfinder supporters while leaving strategic decision-making protocols in the hands of soulless algorithms, or whether it is a living prophecy of Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove can be left up to debate. The fact remains that this is the game plan.

Since both unipolar and multipolar paradigms gripping the Arctic are creating an objective tension which threatens humanity and since appreciation for the origins and evolution of the Russia-China alliance is misunderstood and mischaracterized in the west, a few words of context are in order.

A Brief History of Russian Chinese Arctic Synergy

In 2015, Russia’s Eurasian Economic Union first signed an MOU to integrate with the Belt and Road, and as of 2019, China and Russia signed a series of major programs to extend the Belt and Road Initiative into the Arctic. The synergy between what Prime Minister Medvedev called the “Silk Road on Ice” and Putin’s Great Eastern Vision were obvious and in April 2019, both nations released a joint statement “Joint efforts will be made in Arctic marine science research, which will promote the construction of the ‘Silk Road on Ice.” The statement asserted that both nations “look forward to more fruitful and efficient partnerships worldwide to contribute to the sustainable development of the world oceans and a shared future for mankind.”

During an April 2019 BRI forum, President Putin laid out his concept of Russian and Chinese foreign policy doctrines saying:

“The Great Eurasian Partnership and Belt and Road concepts are both rooted in the principles and values that everyone understands: the natural aspiration of nations to live in peace and harmony, benefit from free access to the latest scientific achievements and innovative development, while preserving their culture and unique spiritual identity. In other words, we are united by our strategic, long-term interests.”

In recent months, the Russian-Chinese Joint Statement on Global Governance of March 23, 2021, represented the clearest response to the collapse of diplomatic bridges uniting west and east whose already weak edifices have been set ablaze in recent months. This diplomatic arson took the form of increased anti-Russian and anti Chinese sanctions, accelerated NATO war games on Russia’s perimeter, increased efforts to consolidate an anti-Chinese Pacific NATO, not to mention Biden’s infamous remarks that Putin was a “soulless killer”. These diplomatic disasters culminated in the infamous ambush of Chinese officials in Alaska on March 19, 2021.

Economic Cooperation and Shared Interests

Russia and China’s collaboration on Arctic resource development has seen both nations focus on transportation corridors, energy and research with a consistently open offer for all nations among their western counterparts to join at any time. Among the most important of the Arctic Projects now underway as part of Russia’s Arctic 2035 Vision announced in 2019, the 6000 km Power of Siberia natural gas pipeline is at the top of the list which will make Russia the primary supplier of China’s energy needs by 2030. This project will be joined by a Power of Siberia II doubling the natural gas output to China via Mongolia and both projects are part of the historic $400 billion energy deal signed between China and Russia in 2014 with the aim of sending 38 billion cubic meters of gas to China for 30 years.

A similar strategic project is the LNG-2 involving Chinese, Japanese, Indian and Russian companies on a joint project showcasing the importance of Polar Silk Road thinking in alleviating tensions among Pacific neighbors. Global energy analyst Professor Francesco Sassi of Pisa University stated that this project “will see an unprecedented level of cooperation between Japanese and Chinese energy companies in one of the most important Russian energy projects of the next decade”.

Additionally China’s 30% stake in the Yamal LNG pipeline which involves the Silk Road Fund ties China’s energy interests ever more deeply into the heart of Russia’s north east.

Russia’s program of expanding Trans Siberian Rail traffic 100 fold from the current 3000 twenty foot units/year to 300 000 twenty foot units/year by upgrading and doubling rail is vital as well as the program for the completion of the Northern Latitudinal Railway connecting west Siberian ports to the Arctic. On the strategic point of shipping, Russia is not only expanding its fleet of icebreakers to include new models of Project 22220 nuclear powered icebreakers, but also will increase freight traffic to 80 million tons/year by 2025 (up from the current 20 million). Several of Russia’s 40 icebreakers are nuclear powered, making it the only nation in the world enjoying this claim… a title it will enjoy until later this year as China rolls out its first 33,000 ton nuclear icebreaker which will join its growing inventory (already far advanced of both Canada’s and the USA’s dismal capacity).

Part and parcel of Russia’s new 15-year plan for the Arctic are plans to commit state support for broad transport and energy infrastructure via direct investments as well as the creation of “economic preference zones” giving private sector actors tax incentives. State support will also be directed towards efforts to mitigate climate change, scientific research, monitoring of environmental damage and pollution clean up.

The Rise of China as an Arctic Powerhouse

China deployed their first Arctic research expedition in 1999, followed by the establishment of their first Arctic research station in Svalbard, Norway in 2004. After years of effort, China achieved a permanent observer seat at the Arctic Council in 2011, and by 2016 created the Russia-China Polar Engineering and Research Center to develop better techniques to access Arctic resources. In 2012, China rolled out its first icebreaker (Snow Dragon I) and has quickly surpassed both Canada and the USA whose two out-dated ice breakers have passed their shelf life by many years.

As the Arctic ice caps continue to recede, the Northern Sea Route has become a major focus for China. The fact that shipping time from China’s Port of Dalian to Rotterdam would be cut by 10 days makes this alternative very attractive. Ships sailing from China to Europe must currently follow a transit through the congested Strait of Malacca and the Suez Canal which is 5000 nautical miles longer than the northern route. The opening up of Arctic resources vital for China’s long term outlook is also a major driver in this initiative.

In preparation for resource development, China and Russia created a Russian Chinese Polar Engineering and Research Center in 2016 to develop capabilities for northern development such as building on permafrost, creating ice resistant platforms, and more durable icebreakers. New technologies needed for enhanced ports, and transportation in the frigid cold was also a focus.

The Questionable Role of Canada in the Arctic Great Game

Amidst this dramatic rate of Arctic development both towards militarization and towards economic cooperation, the Canadian government has managed to remain remarkably aloof and non-committal.

Despite the fact that a 2016 Foreign Policy Review called for Canada’s integration into the northern missile defense shield last championed by Dick Cheney in 2004, Canada’s policy establishment has not committed to any course and while the field remains open for a potential Arctic policy based on diplomacy and cooperation as a bridge between East and West, time is running out.

On the one side, high ranking war hawks among Washington and Ottawa’s policy elite make every effort to court Canada as a participant of the NORAD/NORTHCOM Strategic Vision as the war drums continue to pound. On the other side, Russia has made its desires for Russian-Canadian Arctic cooperation known as Russian chargé d’affaires Vladimir Proskuryakov stated on April 6:

“Despite political difference between our two countries, prospects for Russia-Canadian Arctic cooperation look wide and generally positive. We should only use our possibilities properly.”

Proskuryakov continued: “Being neighbours across the Arctic Ocean, we want to make maximum use of the Arctic potential as a territory of peaceful dialogue and sustainable development, which naturally combines realities and technological solutions of the 21st century with cultural and historic traditions of the indigenous populations.”

If Russia’s hopes for collaboration are to make any headway, then it is certain that Canada’s September 2019 Arctic and Northern Policy Framework will play a role. This framework was an honest attempt by the Federal government to create a “long term strategic vision for activities and investments for Arctic 2030 and beyond”. Having committed to an $800 million fund for Arctic development and amplifying the National Trade Corridors Fund of $2.3 billion/year for 11 years devoted to transportation infrastructure, Canada’s Transportation Minister Marc Garneau called for northern infrastructure proposals in October 2020 with a March 2021 deadline saying:

“Efficient and reliable transportation networks are key to Canada’s economic prosperity. Enhancing Arctic and northern transportation will support trade diversification and social development and ensure greater connectivity for Northerners. I encourage eligible transportation infrastructure owners, operators and users to apply for funding under the National Trade Corridors Fund.”

Sadly, months later, the deadline came and went with no concrete projects placed on the table and no mechanisms established to carry out any potential construction. No funding mechanisms were set in place and without a vision the potential use of the Canadian Infrastructure Bank or Bank of Canada continues to go untapped.

The only concretized policies for the Arctic put in place by the Trudeau government during this time are a stark inversion of actual development with three omnibus bills C-48, C-69 and C-88 passing in short order under the fog of a climate emergency declared by the Parliament. Under these bills, a moratorium was placed on all oil tankers in Northern BC stretching from Vancouver to Alaska (C-48), total bans on offshore drilling were passed declaring Arctic waters off limits to development (C-88) and environmental review processes-already among the most elaborate and bureaucratic among developed nations, was expanded (C-69), making new energy projects in the Arctic nearly impossible.

The Private Sector Steps In

When opportunities to connect Canada’s interests with China were advanced, as seen in the case of China’s efforts to purchase Canadian construction giant Aecon Inc in 2018 or the Hope Bay TMAC Resources in Nunavut in 2020, the Federal Government swept in at the last minute to kill the deals ensuring that no Chinese capital would have any influence in Canada’s development prospects.

Stephen van Dine (VP of Public Governance at Canada’s Institute of Governance) wrote that pension funds, the Canadian Infrastructure Bank and Bank of Canada should be used to play a positive role in arctic development. Van Dine wrote in January 2021: “The Canadian arctic is almost investment-ready for the next 50-100 years with a reliable, predictable infrastructure program for schools, public housing, health centers and power generation. What’s missing is a long-term plan.”

Frustrated with this commitment to inaction, Canadian business leaders at various times formed consortiums outside of the influence of Ottawa as seen in the Alaska-to-Canada Railway Development Corporation which won the support of both the Albertan government as well as former President Donald Trump in September 2020. The A2A Program called for building 2500 miles of rail and finally closing the gap separating Canada from Alaska, which to this day remains one of the most underdeveloped frontiers on earth. Despite the billions of dollars of annual federal transfers to the native bands of each of the northern territories, drug abuse, suicide rates, depression and school drop out rates are magnitudes higher among the static, disconnected northern communities of Canada relative to the national average.

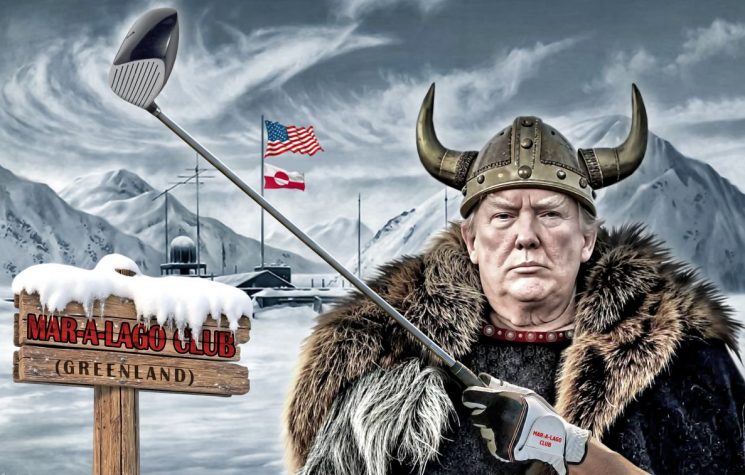

Many were curious if Biden would continue Trump’s support of this program but considering the new president’s swift killing of the Keystone XL pipeline and his passage of Executive Orders ensuring a total halt to all economic development of Arctic resources, the answer has become less ambiguous. These orders made Biden’s ideological stance on Arctic economic development and the A2A Project transparent, and also defined what should be expected of the Biden-Trudeau “Roadmap for a Renewed U.S.-Canada Partnership”.

Another group of thought leaders representing interests in the public, private and academic centers, frustrated at the plague of stasis recently formed a group called Arctic360 with the mandate to drum up support for a positive vision for Canada’s High North. Comparing Canada with other members of the Arctic Council, Jessica Shadian (President and CEO of Arctic360) wrote:

“When it comes to Canada’s truly competitive advantage for becoming a global leader in innovation it is time to break out of the usual mould and go where few Canadians go: the North. One just needs to glance at Canada’s Nordic Arctic neighbours to see that there is precedence. The often-made arguments as to why the North is an inopportune place for everything from living to working to starting a business or building a road is its real advantage. That the North is vast, cold, remote, dark six months of the year, has harsh weather and a critical infrastructure gap is one of Canada’s biggest innovation assets. Add to this, that the North is home to many of the critical minerals that China and others want for building technologically advanced infrastructure. The North could be Canada’s unrealized key to leap-frog existing infrastructure and industries and play a global leadership role in 21st Century innovation. The question is whether we have the ambition or the conviction to lead.”

A True Vision for Inter-Civilizational Cooperation: The Bering Strait Corridor

It was in March 2015, foreseeing the Arctic extension of the Belt and Road Initiative by a number of years, that former Russian Railways president Vladimir Yakunin, brilliantly called for a Trans-Eurasian Development Belt with rail stretching all the way up to the Bering Strait crossing and integrating into Asia. Yakunin, who for years has been a proponent of the connection of the Americas and Eurasia by rail, said the project should be an “inter-state, inter-civilization, project. It should be an alternative to the current (neoliberal) model, which has caused a systemic crisis. The project should be turned into a world ‘future zone,’ and it must be based on leading, not catching, technologies.”

Having been originally conceived in the 19th century as outlined by Governor William Gilpin in his 1890 Cosmopolitan Railway, and supported by Czar Nicholas II who sponsored feasibility studies on the project in 1906, the Bering Strait tunnel connecting Eurasian and American continents fell from general awareness for decades. It was briefly revived during discussions held between FDR’s Vice President Henry Wallace and Russian Foreign Minister Molotov in 1942 but was again lost under the fog of Cold War insanity. This century-old idea again resurfaced when Russia signaled its willingness to construct the project in 2011 offering over $65 billion towards its funding, which only required the cooperation of the United States and Canada. China put its support behind the Bering Strait Tunnel in May 2014.

While such a grand design would provide the most direct pathway for the west to synchronise our development paradigm with the Polar Silk Road, and Greater Eurasian Partnership, it is admittedly a far cry from the realities plaguing current geopolitical thinking.

The best that can be hoped for in the short term would be a successful war avoidance strategy adopted by Ottawa in alignment with Moscow’s desires for cooperation on the field of anti-coronavirus programs, education and arctic medical needs and environmental management. If these simple trust building mechanisms can begin to take hold, and if war hawks are kept at bay, then perhaps Canada can eventually play the role of intermediary and diplomatic bridge both for the benefit of its own citizens and the wellbeing of the world as a whole.