While Bolsonaro may have recently stirred a rift between the government and the military, any divergences or differences of opinion or strategy between both entities will still veer toward the right-wing ideology.

In July 1963, the Kennedy administration decided it had to “do something about Brazil.” The U.S. role, at the time, was to destabilise the country, which is did through the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) between 1961 and 1963, while considering the options to bring Brazil to a compliant approach with U.S. imperialist interests. President Joao Goulart could either purge the left-wing from this government, or else face a military coup, which by 1962 was already considered the preferable option.

On March 31, Brazil’s armed forces, backed by the U.S., staged a military coup which forced Goulart into exile in Uruguay. The U.S. immediately recognised the military government, which paved the way for widespread torture of opponents. Statistics indicate a lesser number of disappeared civilians in Brazil than Chile and Argentina, for example. However, the use of torture was rampant and the primary method used to quash out any resistance to the dictatorship. More than 50,000 Brazilians were detained and tortured, while 10,000 were forced into exile.

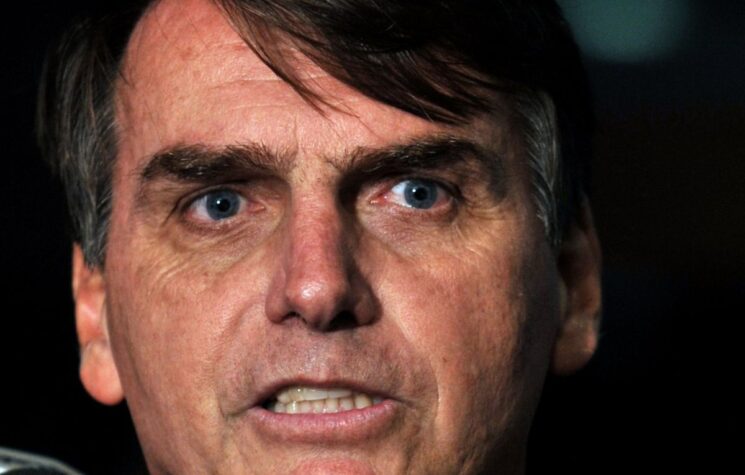

Under the current Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, the military dictatorship stirred up the country’s memory in a brutal manner. While in 2011, the Brazilian Congress voted in favour of a bill to set up a truth commission as a primary step towards justice and building the country’s collective memory, Bolsonaro has tried to emulate dictatorship tactics within a democratic framework through his policies, the political attacks upon the indigenous communities, education, as well as giving the right-wing the space to flourish once again in the country.

The recent commemorations of the coup by several Brazilian officials and influential individuals attest to the government’s normalisation of right-wing violence. “We are here to celebrate the expulsion of communists from the Brazilian government,” a businessman declared.

With no accountability so far in terms of establishing culpability over torture, Bolsonaro has exploited the vacuum that prevails in place of memory. In 1974, for example, the Brazilian President Ernesto Geisel gave the order to continue the “summary execution of dangerous subversives,” as detained in a memorandum to Henry Kissinger, the U.S. Secretary of State at the time. The document states that 103 Brazilians were executed by extra-legal methods in 1973.

Declassified documents presented in 2014 to former Brazilian President Dilma Roussef detail the torture and execution methods employed by the military dictatorship. One method used to eliminate identification of bodies was termed “sewing” – shooting a person from head to top with an automatic weapon. The dictatorship’s preferred cover-up for the elimination of its opponents was the fabrication of a shoot-out – claiming that prisoners were shot while attempting to escape.

Defence Minister Walter Braga Netto insisted upon the “right” to celebrate the coup, saying, “The armed forces ended up assuming the responsibility of pacifying the country, facing the challenges of reorganising it and securing the democratic liberties that we enjoy today.” But if the coup secured freedom, why would it have had to resort to oppression to annihilate what it allegedly procured?

While Bolsonaro himself refrained from making any remarks as opposed to previous years, the discourse of purported pacification from one of the country’s top officials is an embodiment of Bolsonaro’s constant praise for dictatorship crimes. Furthermore, it places obstacles to the people’s right to justice and memory by appealing to the younger generation’s right-wing glorification, thus setting the country up for a possible political rupture. And while Bolsonaro may have recently stirred a rift between the government and the military, any divergences or differences of opinion or strategy between both entities will still veer toward the right-wing ideology that Bolsonaro has promoted since his foray into politics, and more vociferously, since he was elected president.