At the explicit level, today’s geo-political struggle is about the U.S. maintaining its primacy of power – with financial power being a subset to this political power. Carl Schmitt, whose thoughts had such influence on Leo Strauss and U.S. thinking generally, advocated that those who have power should ‘use it, or lose it’. The prime object of politics therefore being to preserve one’s ‘social existence’.

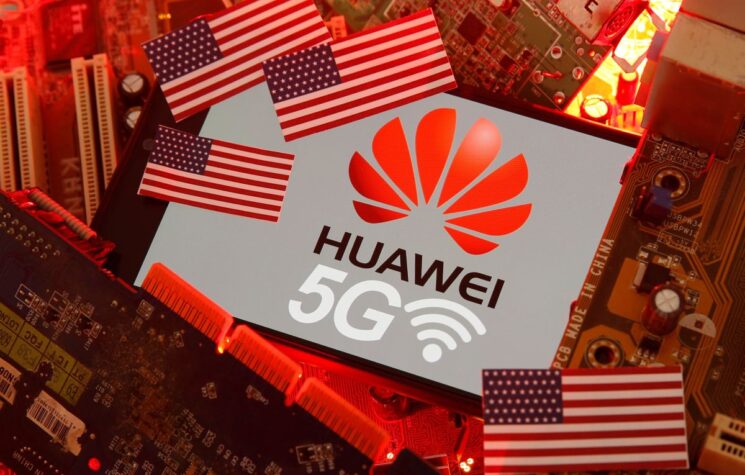

But at the underside, Tech de-coupling from China is one implicit aspect to such a strategy (camouflaged beneath the catch-phrase of recovering ‘stolen’ U.S. jobs and intellectual property): The prize that America truly seeks is to seize for itself over the coming decades, all global standards in leading-edge technology, and to deny them to China.

Such standards might seem obscure, but they are a crucial element of modern technology. If the cold war was dominated by a race to build the most nuclear weapons, today’s contest between the U.S. and China — as well as vis à vis the EU — will at least partly be played out through a struggle to control the bureaucratic rule-setting that lies behind the most important industries of the age. And those standards are up for grabs.

China has long been strategically positioning itself to fight this ‘war’ of tech standards (i.e. China Standards 2035, a blueprint for cyber and data governance).

The same argument is true for supply-chains which are now at the centre of a tug-of-war that has major implications for geopolitics. Dis-entangling the rhizome of supply chains built-up through decades of globalism is difficult and onerous: The multinational companies which sell into the Chinese market may have little choice but to try to stay put. However, if de-coupling as a key U.S. foreign policy persists, then products ranging from computer servers, to Apple iPhones, could end up having two separate supply chains — one for the Chinese market, and one for much of the rest of the world. It will be more costly and less efficient, but this is the way that politics is pushing (at least for now).

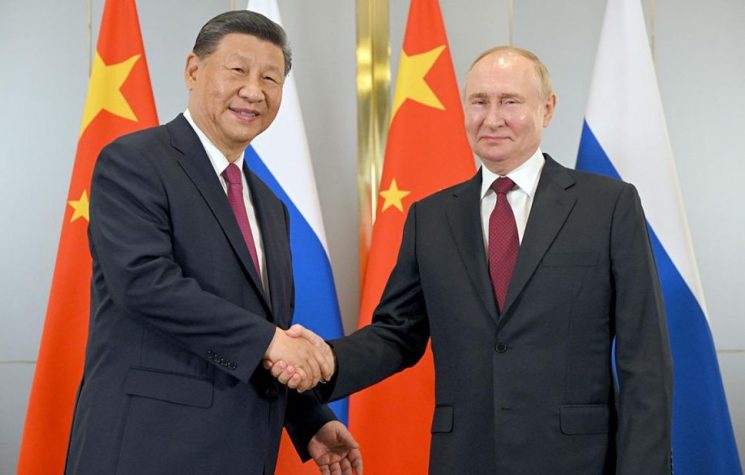

So where are we in this de-coupling struggle? Until now, it is a mixed bag. The U.S. has focussed on de-coupling in certain leading-edge technologies (that also have dual civil-defence potential). But Washington and Beijing have stayed clear of financial de-coupling (so far) – as Wall Street does not want to lose a $5 trillion two-way financial trade.

Some years back, when travelling across Europe, passengers commonly had to exit one train on reaching the frontier, and cross to a different train and carriages, beyond the border. This still exists. The railways were operating on entirely different gauge rail tracks. We have not reached that point in Tech. But the future is likely to become more complex – and costly – should Europe, the U.S. and China adopt different protocols for 5G. The latter, with its low latency, enables diverse strands of data to be mined, and modelled, in near real time (a game-changing factor for missile targeting and aerial defence systems, where every millisecond counts).

It is possible then, that 5G may be divided into two competing stacks to reflect different U.S. and Chinese standards? For outsiders to compete, they may find it necessary to manufacture separate equipment for these different protocols. Some measure of division is also possible in semiconductors, artificial intelligence and other areas where U.S.-China rivalry is intense. For now, Russia and Iranian infrastructure is fully compatible with China. The West is not yet a ‘separate gauge’; it can still work with Iran and Russia, but dual-functionality in the tech sphere nevertheless will cost — and probably require careful legal workabouts, to avoid legal or regulatory sanction.

And just to be clear, the battle for influence over Tech standards is separate to the ‘Regulatory War’ in which the Data, AI and the Regulatory eco-spheres are being ‘Balkanised’. Europe is almost non-existent in the Cloud analytics sphere, but is trying to catch-up quick. It must. China is so far ahead that Europe has little choice but to bulldoze (strong arm) its way into this space i.e. by ‘regulating’ U.S. Cloud business (already under U.S. anti-trust threat), toward Europe.

Cloud companies provide their clients with data storage, but also with sophisticated tools for analysing, modelling, and understanding the vast data sets found in the cloud. The sheer size of modern data sets has sparked an explosion of new techniques for extracting information from them. These new techniques are made possible by ongoing advances in computer processing power and speed, as well as by aggregating computer power to improve performance (known as High-Performance Computing, or HPC).

Many of these techniques (‘data mining’, ‘machine learning’, or AI) refer to the process of extracting information from raw data. Machine learning refers to the use of specific algorithms to identify patterns in raw data and represent the data as a model. Such models can then be used to make inferences about new data sets or guide decision-making. The term ‘Internet of Things’ (IoT) usually refers to a network of connected computing and physical devices that can automatically generate and transmit data about physical systems. The ‘nervous system’ serving such ‘body messaging’ will be 5G.

The EU is already regulating Big Data; it intends to regulate the U.S. Cloud platforms; and is looking at setting EU protocols for algorithms (to reflect EU social objectives and ‘liberal values’).

All those companies that are dependent on Cloud analytics and machine training, therefore, will be affected by this Regulatory fragmentation into distinct spheres. Companies, of course, need these capabilities to run robotics and complex mechanical systems effectively – and to reduce costs. Analytics has been responsible for huge productivity gains. Accenture estimate that analytics alone could generate as much as $425 billion in added-value, by 2025, for the oil and gas industry.

It was the U.S. that triggered this round of de-coupling, but the consequence to that initial decision is that it has prompted China to respond with its own de-coupling from the U.S. at the leading-edge of Tech. China’s intent now is not simply to refine and improve on existing technology, but to leapfrog existing knowledge into a new tech realm (such as by discovering and using new materials that overcome present limits to microprocessor evolution).

They may just succeed – over next the three years or so – given the huge resources China is diverting to this task (i.e. with microprocessors). This could alter the whole tech calculus – awarding China primacy over most key areas of cutting-edge technology. States will not easily be able ignore this fact – whether or not they profess to ‘like’ China, or not.

Which brings us to the second ‘underside’ to this geopolitical struggle. So far, both the U.S. and China have kept finance largely separate to the main de-coupling. But a substantive change may be underway: The U.S. and several other states are toying with Central Bank digital currencies, and FinTech internet platforms are beginning to displace traditional banking institutions. Pepe Escobar notes:

Donald Trump is mulling restrictions on Ant’s Alipay and other Chinese digital payment platforms like Tencent Holdings…and, as with Huawei, Trump’s team is alleging Ant’s digital payment platforms threaten U.S. national security. More likely is that Trump is concerned Ant threatens the global banking advantage the U.S. has long taken for granted.

Team Trump is not alone. U.S. hedge fund manager Kyle Bass of Hayman Capital argues Ant and Tencent are “clear and present dangers to U.S. national security that now threaten us more than any other issue.”

Bass estimates that the Chinese Communist Party is pushing its yuan digital payment system on an estimated 62% of the world’s population in ways that threaten Washington’s influence. What started as a mere online payment service has since veered sharply into a financial services juggernaut. It’s becoming a powerhouse in loans, insurance policies, mutual funds, travel booking and all the cross-platform synergies for sales and economies of scale.

At the moment, well over 90% of Alipay users are using the app for more than just payments. This is “effectively creating a closed-loop ecosystem where there is no need for money to leave the wallet ecosystem,” says analyst Harshita Rawat of Bernstein Research.

Rawat notes that Ant has “used its payment service as a user acquisition engine for building broader financial services features.” That includes finding ways to cross-pollinate Ant’s ambitions to be China’s financial services mall with Alibaba’s dominant online bazaar…

Given that many Chinese already downloaded the Alipay app, CEO Eric Jing is angling to export its model overseas. It’s collaborating with nine start-ups around the region, including GCash in the Philippines and Paytm in India. Ant plans to use the proceeds from its share listing to accelerate the pivot overseas.

The point here is two-fold: China is setting the scene to challenge a fiat dollar, at a sensitive moment of dollar weakness. And secondly, China is placing ‘facts on the ground’ — shaping standards from the bottom up, through widespread overseas adoption of its technology.

Just as Alipay has made huge inroads across Asia, China’s ‘Smart Cities’ project diffuses Chinese standards, precisely because they incorporate so many technologies: Facial recognition systems, big data analysis, 5G telecoms and AI cameras. All represent technologies for which standards remain up for grabs. Thus ‘smart cities’, which automate multiple municipal functions, additionally helps China’s standards drive.

According to research by RWR Advisory, a Washington-based consultancy, Chinese companies have done 116 deals to install ‘smart city’ and ‘safe city’ packages around the world since 2013, with 70 of these taking place in countries that also participate in the Belt and Road Initiative. The main difference between ‘smart’ and ‘safe’ city equipment is that the latter is intended primarily to survey and monitor the population, while the former is primarily aimed at automating municipal functions while also incorporating surveillance functions. Cities in western and southern Europe together have signed up to a total of 25 such ‘smart’ and ‘safe’ projects.

Mark Warner, Democratic Vice-Chair of the U.S. Senate intelligence committee, sees the threat from China in stark terms: Beijing intends to control the next generation of digital infrastructure, he says, and, as it does so, to impose principles ‘that are antithetical to U.S. values’. “Over the last 10 to 15 years, [the U.S.] leadership role has eroded and our leverage to establish standards and protocols reflecting our values has diminished,” Warner laments: “As a result others, but mostly China, have stepped into the void to advance standards and values that advantage the Chinese Communist party”.

All signs point to China wielding more influence over global technological standards. Yet equally certain is that the backlash from Washington is building. Should the U.S. become more confrontational, it could lead China to accelerate a move towards parallel alternatives. This could ultimately result in a bifurcated arena on industrial standards.