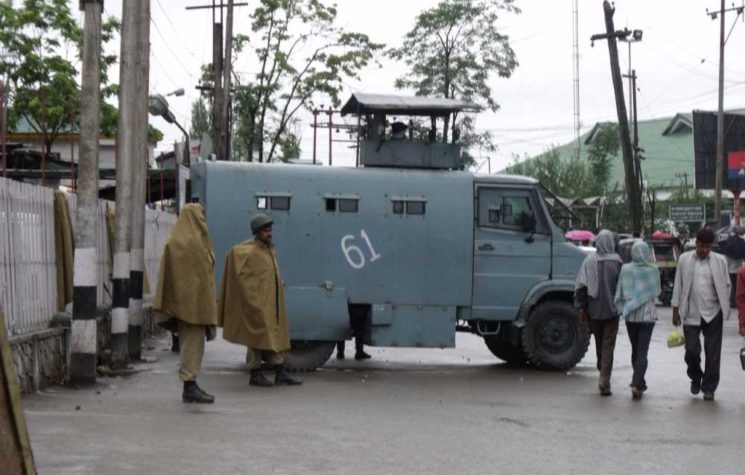

By abrogating the autonomous status of the now-former state of Jammu and Kashmir and transforming it into two direct rule territories, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi may have set in motion forces that could result in challenges to its control of portions of the Himalayan region.

On October 31, the new Indian union territories of Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh were officially bifurcated. Neither enjoy the autonomous self-governing status as that of the former State of Jammu and Kashmir. Jammu and Kashmir became the first Indian state to be reduced from a state to a union territory, something that has alarmed other states that have had a contentious relationship with New Delhi. During her time as prime minister, Indira Gandhi often dismissed the governments of various states and imposed direct rule from New Delhi, however, she never downgraded the status of an Indian state.

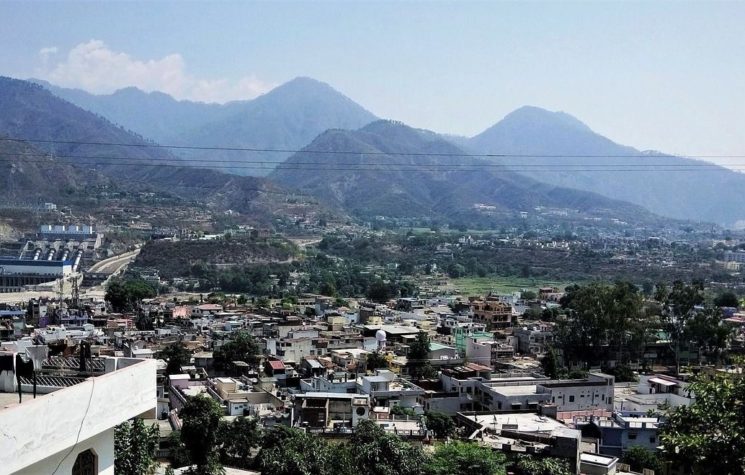

Leh, the capital of Ladakh, which is largely Buddhist, was generally happy about its separation from Muslim-dominated Jammu and Kashmir. However, that was not the case in Ladakh’s district of Kargil, which has a majority Muslim population. Most of the Muslims of the district are Shi’as, who have their own grievances with the Sunnis of the rest of Kashmir, as well as those in Pakistan. Residents and members of the Kargil Hill Development Council observed their new status with an October 30th “Black Day,” with protesters hitting the streets of Kargil to decry their downgraded status. The protests followed a four-day general strike that shut down business in the district. The bifurcation and restlessness in Kargil have some quarters in New Delhi concerned. The Buddhists in Leh and the Shi’as in Kargil have actually managed to coexist amicably in recent years. Both have reasons to be suspicious of Sunni troublemaking in the region spurred on by the Pakistani Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) agency and Wahhabist Sunni provocateurs funded by Saudi Arabia.

In 1999, Kargil was ground zero for deadly Sunni Islamist terrorist actions and an Indian-Pakistani military conflict. The Lashkar-e-Toiba (LET) and Al-Faran Islamist terrorist groups, backed by ISI, had previously conducted attacks against foreign tourists, including the beheadings of foreign hostages. Faced with the threat posed by Wahhabi-influenced terrorists, the Buddhists of Ladakh and Shi’a majority in Kargil have formed a somewhat united front. One point of contention arose in the 1990s in Leh, when the Sunni mosque in the town center began issuing forth incendiary anti-Buddhist messages from the loudspeaker normally used for the Muslim calls to prayer.

Neither the Ladakh Union Territory nor the new Jammu and Kashmir Union Territory have elected legislatures. Instead both have Lieutenant Governors answerable only to the Modi government. The new Lieutenant Governors — Radha Krishna Mathur in Ladakh and Girish Murmu in Jammu and Kashmir – are retired officers of the Indian Administrative Service (IAS) – India’s own version of the “deep state,” a permanent civil service bureaucracy left over from the British colonial era. Mathur is also the former Indian Chief Information Commissioner, a post he left in 2018. He also served as the central government’s Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises Secretary and Defense Production Secretary. With his experience in the defense sector, there was no surprise when Murmu said his main focus will be on “sensitive border areas.” That equates to keeping a close watch on China and Pakistan in the mountainous region.

The Member of the Lok Sabha who represents Ladakh, Jamyang Tsering Namgyal, called the bifurcation of Jammu and Kashmir and the creation of the Ladakh Union Territory an “inclusive development plan” for the region. Under the previous state administration in Srinagar, the Buddhists of Ladakh felt left without a voice in local government. Although Namgyal is a member of Modi’s Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), the political alignment was for convenience, since the Buddhists of Ladakh did not have the political pull to engineer its separation from the former Jammu and Kashmir state. Previous alignment of Ladakh Buddhists with the Indian Congress Party of Jawaharlal Nehru, Indira Gandhi, and other Congress prime ministers never yielded any final agreement to separate Ladakh from the rest of Jammu and Kashmir.

Now that the Buddhists of Ladakh have a separate political voice, they are using it to their advantage. Former Buddhist members from Ladakh in the now-defunct Jammu and Kashmir Legislative Assembly are demanding that they be included in the Sixth Schedule of the Indian Constitution, which ensures cultural and economic protections for India’s tribal peoples.

Modi may have ignited long suppressed Buddhist nationalist resentment that extends from Ladakh in the western Himalayas to Sikkim in the central Himalayas and into Arunachal Pradesh in the east. China, ostensibly on behalf of the Tibetan Autonomous Region, has land claims along the entire Indian frontier. Another factor is the Dalai Lama of Tibet, whose Tibetan government-in-exile makes Dharamsala in India its home.

Now that Ladakh has a separate identity from Jammu and Kashmir, albeit a territorial one without representation in the former Legislative Assembly in Srinagar, Buddhist identity movements, such as the Ladakh Buddhist Association (LBA) and the Ladakh Union Territory Front (LUTF), feel emboldened to stake their political, cultural, and economic claims. The LBA believed the former Muslim-dominated state government of Jammu and Kashmir was hostile to Buddhist interests in Ladakh. Because of its distrust of the state government, the LBA was always in favor of bifurcation of Ladakh from Jammu and Kashmir and even trifurcation of Jammu, Kashmir, and Ladakh, into majority Hindu, Muslim, and Buddhist states, respectively.

Ladakh only had four seats in the former Jammu and Kashmir Legislative Assembly. It continues to retain its one seat in the Lok Sabha, currently filled by the BJP’s Jamyang Tsering Namgyal. Although the Buddhist Ladakhis have been given a respite from the Muslim political interests that had a monopoly of power in the old Jammu and Kashmir, they also fear being overrun by Hindus desiring to escape the increasingly hotter temperatures of the Indian coast and Deccan Plateau for the cooler climes of the Himalayan region.

With Ladakhis now free of control from Srinagar and the old Jammu and Kashmir state, they may begin, as a cohesive unit, to reach out to fellow Buddhists in other parts of India. The Buddhist Bhutias and Lepchas of Sikkim, an Indian state wedged between Nepal and Bhutan – the latter a Buddhist kingdom — long for the era of Sikkim’s independence under a Buddhist king or “Chogyal.” Sikkim lost its independence in 1975 after the Indian army invaded the kingdom, deposed the Chogyal, and presided over the annexation of Sikkim to India as a state. There is not only an increasing nostalgia for the kingdom among the Buddhists, but some of the majority Nepalese Hindus have also displayed a yearning for the lost kingdom.

Buddhist national identity has taken on violent excesses in countries like Myanmar and Sri Lanka. But in the Himalayas, which is the birthplace of Gautama Buddha, Buddhism is attempting to make a resurgence in a political sense. Had the region not fallen prey to the Cold War interests of India, China, and the United States, a region of independent Buddhist states – Ladakh, Sikkim, and Bhutan – and semi-independent Buddhist principalities – Mustang in Nepal and Tawang in Arunachal Pradesh – may have emerged to provide a neutral buffer between India and China. With recent developments in Ladakh and Sikkim, such a future outcome may not be totally out of the question.