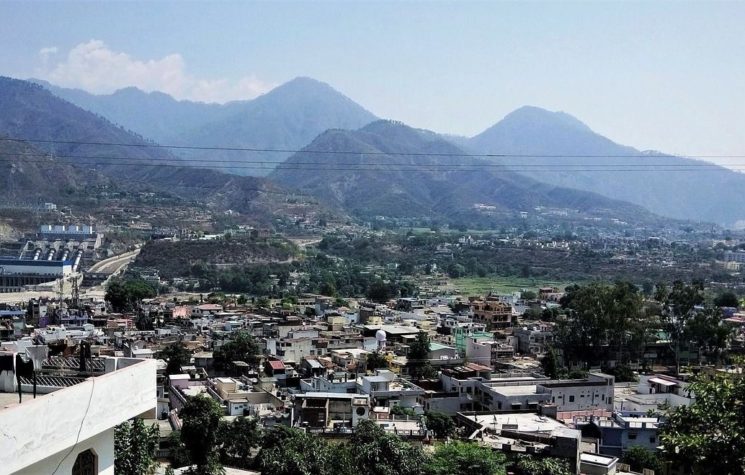

In early August India deployed 38,000 troops in Indian-administered Kashmir to join the half-million already there. (There are two Kashmirs, administered respectively by India and Pakistan, following post-colonial dissent concerning accession of the territory.) There was then a massive clamp-down after a decree of 5 August annulled Article 370 of India’s Constitution which guaranteed the rights of Kashmiris to freedom under local laws. The region was subjected to military occupation, with central rule imposing unprecedented restrictions on movement and banning communication with the outside world. These have been enforced for over six weeks.

Associated Press managed to report some incidents, however, including one when “Indian soldiers descended on Bashir Ahmed Dar’s house in southern Kashmir on August 10… Over the next 48 hours, the 50-year-old plumber said he was subjected to two separate rounds of beatings by soldiers. They demanded that he find his younger brother, who had joined rebels opposing India’s presence in the Muslim-majority region… In a second beating at a military camp, Dar said he was struck with sticks by three soldiers until he was unconscious.” They released him but “on August 14, soldiers returned to his house… and destroyed his family’s supply of rice and other foodstuffs by mixing it with fertiliser and kerosene.”

Although there was a petition on 12 September to President Trump by four US Senators “to immediately facilitate an end to the current humanitarian crisis” in Indian-administered Kashmir, there has not been one syllable of condemnation by the administration in Washington. London remained silent also. These energetically vociferous supporters of human rights have voiced not the slightest criticism of India for its persecution and imprisonment of innocent Kashmiris.

Why?

If this sort of thing had happened in Crimea there would have been massive coverage in the Western media and loud and penetrating censure and denunciation of Moscow by politicians, pundits and the ever-attentive US military.

Western media always refer to the 2014 accession by Crimea to Russia as ‘annexation’ by Russia of the land that is historically Russian, whose citizens are predominantly Russian-speaking and Russian-cultured, and whose government held a referendum which overwhelmingly indicated preference for accession to Russia. One would not know it from Western media, but the referendum was witnessed by 135 international observers from 23 countries, including the Austrian MP Johannes Hübner who said that “The view we get from the American and European media is very distorted. You get no objective information. So we decided to come here to have a look at what’s really going on and see if this referendum is credible”. Which it was.

In contradistinction, there has been no referendum in Kashmir, as required by international legislature. In January 1949 the UN Commission for India and Pakistan announced that “The question of the accession of the State of Jammu and Kashmir to India or Pakistan will be decided through the democratic method of a free and impartial plebiscite” and the BBC notes that “in three resolutions, the UN Security Council and the United Nations Commission in India and Pakistan recommended that as already agreed by Indian and Pakistani leaders, a plebiscite should be held to determine the future allegiance of the entire state.”

But it seems that Western governments are given to condemning referendums when they don’t suit their purpose and ignoring UN Resolutions to hold them when that action would be embarrassingly inconvenient for the country involved.

There’s no freedom in Kashmir, and instead of enjoying a modicum of self-governance and being permitted a referendum on its future, Indian-administered Kashmir is subjected to what is called ‘lockdown’. Mobile phone networks and access to the internet have been blocked for over six weeks — and there hasn’t been an official syllable of disapproval in Washington or London. Certainly, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Michelle Bachelet, said on 9 September that she is “deeply concerned about the impact of recent actions by the government of India on the human rights of Kashmiris” and also “alarmed” about “restrictions on internet communications and peaceful assembly, and the detention of local political leaders and activists” — but no Western government paid the slightest attention. Nor did the freedom-loving Western mainstream media, which is always alert for violations of human rights around the world. Well — in some parts of the world.

They ignore the savagery of Indian troops and the denial of basic freedoms in Indian-occupied Kashmir, but would they do that if such excesses were evident elsewhere? Imagine the uproar, the feverish surge of self-righteous passion, the fiercely critical condemnation of brutality and suppression of democracy if anything like this occurred in Crimea. The US and Britain would go berserk with sanctimony.

On 12 September Reuters reported that “Authorities in Indian Kashmir have arrested nearly 4,000 people since the scrapping of its special status last month, government data shows, the most clear evidence yet of the scale of one of the disputed region’s biggest crackdowns… More than 200 politicians, including two former chief ministers of the state were arrested.”

But Mr Trump didn’t say a word. He was otherwise occupied, tweeting insults, and while repression was surging in Kashmir was at a G-7 meeting in Biarritz where he referred to Egypt’s tyrannical Abdel Fattah al-Sisi as “my favourite dictator” which tells us a great deal about the outlook of the US President. It is not surprising that Trump doesn’t want to criticise Indian Prime Minister Modi, the director of despotism in Kashmir, as he considers that “Prime Minister Modi and I are world leaders in social media.” His final G-7 tweet was that he had “Just wrapped up a great meeting with my friend Prime Minister Modi of India at the G-7 Summit in Biarritz, France!” so it seems that the twitter soul mates approve of ultra-authoritarianism and that Trump isn’t going near the Kashmir human rights’ button anytime.

Britain’s Prime Minister Johnson is desperately trying to avoid the catastrophic outcome of quitting the European Union and has little time for wider affairs, so cannot be expected to say anything definitive about the atrocities in Kashmir other than his pronouncement of 9 August that the situation was “serious.” His stance on Crimea is set in the Western mould of ‘annexation’ and he is rabidly anti-Russia, so there is no chance of a movement to dialogue by the United Kingdom. The rest of Europe just wishes the Kashmir crisis would go away, and hangs on to the ‘annexation’ story about Crimea, where there was no ‘lockdown’, persecution or detention of innocent civilians at accession time. Imagine the furore if there had been use of pellet guns in Sevastopol.

Amnesty International’s Secretary General, Kumi Naidoo, urged the Indian government “to act in accordance with international human rights law and standards towards people living in Jammu and Kashmir, including in relation to arrests and detentions of political opponents, and the rights to liberty and freedom of movement” and pointed out that “The actions of the Indian government have thrown ordinary people’s lives into turmoil, subjecting them to unnecessary pain and distress on top of the years of human rights violations they have already endured.”

Will there be any action at all by Washington and London? No: not a hope. They’ll continue to bounce up and down about Crimea, where there is liberty and freedom of movement, while keeping silent about persecution in Kashmir.

They are looking at the world through a prism of hypocrisy.