The failure to take into accurate account the vast changes and growth in the world’s physical economy is on display in the case study of Venezuela, whose leadership reflects a rational model, but which does not follow the diktats of the Washington Consensus.

On May 25th the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs released an official statement to the effect that representatives of the US-appointed man in Venezuela, Juan Guaido, and representatives of the government of Venezuela, would meet again in Oslo this week to further a political dialogue.

The aim is to find a political solution to the US invented crisis in Venezuela. The hope is that it would avoid an open military conflict, and a possible relief of the sanctions policy that has hindered critical elements of the Venezuelan economy and human and social services. More to the point in the EU’s interest, is to stabilize the Venezuelan government and use the Oslo talks as both a symbolic and real vehicle to give assurances to European and Venezuelan elites who are under pressure from Washington Consensus, neoliberal politics.

The US is disturbed at the probability that its entire regime-change gambit has failed, and has disavowed the entire Oslo process. US Vice President Mike Pence, expressing his disappointment with the specter of rapprochement between Venezuelans, said shortly before the new announcement from Norway, that the time for dialogue “is over”, stating that “it is time for action” when referring to Venezuela.

The US appointed representatives in Venezuela such as Juan Guaido’s team, have expressed their extreme disappointment at this second round of talks in a mirrored way. It reflects, as they fear, a lack of cohesion between the transatlantic partners on the question of Venezuela. While it is common to speak of ‘international sanctions against Venezuela’, the most cutting and thorough are those from the United States, while the EU’s focus specifically on a smaller group of individuals and a ban on military related materials transactions – transactions which Venezuela was hardly reliant on and generally showed no interest in to begin with.

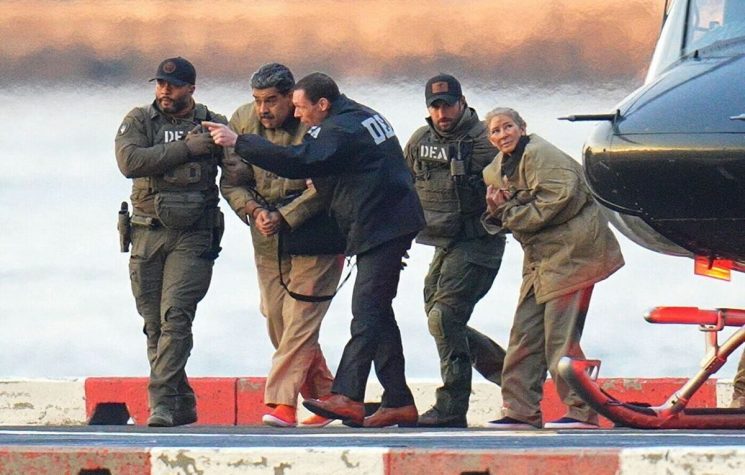

On May 26th, a critical opposition figure, leader, and fugitive from the Venezuelan justice system, Antonio Ledezma, started a live talk from his Twitter account asking a set of rhetorical questions. “What is going on now in Norway? Dialogue? What is that? Ingenuity? Error? Who supports it? Who takes advantage of this gamble?” Ledezma inquired with exasperation.

Ledezma made it more than openly clear that he is entirely opposed to the meeting in Oslo: “Maduro and his mafia carve up the National Assembly and go to Norway as usurpers. I support Juan Guaidó but my responsibility is to say that I do not agree with the Norwegian format.”

The Spanish government in particular, representing the fact that Spanish capital interests in Venezuela remain solid and continue to express confidence in the PSUV government, have lambasted US policy on Venezuela. Spain’s relationship to Venezuela is profound, in in turn, successful Spanish obligations vis-à-vis Germany rely on a degree of solvency which Spain finds in Venezuela.

For example, on Wednesday May 8th Spanish Foreign Minister Josep Borrell spoke live on the state-owned channel TVE, saying that the US is acting “like the cowboys in the Far West, saying ‘careful or I’ll draw’.” His position, like that of the EU, as evidenced by the Oslo process, is that the solution to the Venezuelan crisis can only be “peaceful, negotiated and democratic.”

It should be noted also of course symbolically, that Oslo is an expression of the EU as problem-solver in the face of problem-creation stemming from the US’ post-Bretton Woods crisis.

The Norwegian Foreign Ministry said in a statement reiterating its commitment to seek “an agreed solution” between the parties, while being delicately diplomatic in their treatment of the fact that the ‘other’ Venezuelan party is in fact simply the United States. “We inform that the representatives of the main political actors of Venezuela have decided to return to Oslo next week to continue a process facilitated by Norway.”

When the US initially launched the formal phase of its regime-change gambit in Venezuela, they were successful in creating enough political momentum to encourage leading EU member states back in the last week of January of this year, to call on Maduro to make new elections within eight days, or face certain consequences.

Transatlantic media succeeded in creating a short-lived media hologram in which these consequences were explained as ‘recognizing Juan Guaido as the interim president of Venezuela’, when this was not the consequence at all. This bluff was successfully called, new elections were not called in Venezuela, and the EU’s real position was revealed in time.

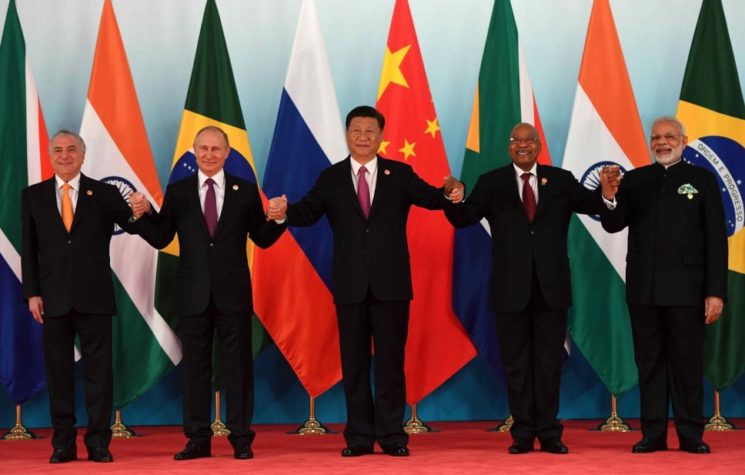

Such a media hologram may have even promised to convince those elements of the Venezuelan industrial/financial elite, and military, that the PSUV led government was in its last days. But this was not the case, and this did not materialize. That said, the EU is looking for an exit to this impasse, and recognizes the significance of its own relationship with China and Russia, who in turn are heavily invested in Venezuela under its present regime of obligations; the very same obligations that would be reneged upon in the event that regime change occurred in Venezuela.

Likewise, despite Venezuela being under severe US sanctions, and that Venezuela has not undertaken to clear its status with the IMF for over a decade (since 2007), or more clearly has not been allowed to in such a way consistent with its own sovereignty, the EU and its other international partners increasingly are aware that it is US policy that is out of alignment with the international community.

Nevertheless, US sanctions on Venezuela also affect partners engaged in direct transactions with the Bolivarian republic such that the specter of litigation and restricted trade for various global firms including those in the EU, has had a cooling effect overall.

At the same time, there is more here than meets the eye, and reflects a growing desire on the part of multilateral financial actors to be able to engage transparently and directly with Venezuela, and to do so means to restructure the US’ role in the primary post-war multilateral finance, capital, and development institutions that were issued from Bretton Woods, such as the IMF.

This problem, as it were, has even led to Venezuela’s creation of a hard-to-track crypto currency, the Petro, so that it could engage with various multilateral financial actors, perhaps even including some American firms, as an end-run around the US sanctions regime.

In short what we are seeing is that the EU views Venezuela as a focal point for this divergence over how to manage the decline of the USD as the world’s reserve currency. Wanted is its replacement with a system backed by a basket currency and a more coherent multipolar system more alike the proposal of Maynard Keynes’conception of an ICU, or international clearing union, although other proposals and remedies which take into account the peculiarities of the present technological and military impasse are also credible and on the table.

Norway’s role here is more than apparent – it is a proxy for the EU consensus in general. Despite initial misreporting across Atlanticist media outlets that the EU was in alignment with the US over the status of Guaido and the inevitability of the collapse of the Venezuelan government led by the PSUV, this second round of Oslo talks is representative of the contrary.

Indeed, in the continuing and unfolding saga of the US’ gambit to conduct a ‘regime change’ operation in Venezuela, the latest developments show a growing rift between the EU and the US.

At face value, the major transatlantic banks which come together, for example, to form the IMF, seem often times to present a united front. But behind this front there is instead a steadfastly growing variance over a range of issues, from energy projects involving Russia and Iran, the development of the Chinese belt and road initiative, as well as this case which centers Venezuela; the summation of all of these issues simultaneously.

All together this echoes an increasing assessment that the US dollar has lost its preeminence as the world’s reserve currency, as it has been increasingly displaced by a basket of currencies including, for example, the increasingly independent Euro and the Yuan. One of the key subjects in understanding this revolves around the abandonment of the critical informal regimes of the Bretton Woods system, even while formal aspects of the institutions it engendered (the IMF and WB) exist on in altered form.

If we understand Bretton Woods as consisting of both formal regimes such as the IMF and World Bank, and informal regimes such as the fixed (or pegged) exchange rates system and the use of gold to back the dollar (which in turn was the primary currency), then we see that the informal regimes which made the IMF a coherent system for economic growth and stability, have not been in effect since the Nixon era.

The failure to take into accurate account the vast changes and growth in the world’s physical economy is on display in the case study of Venezuela, whose leadership reflects a rational model, but which does not follow the diktats of the Washington Consensus. That numerous – even leading – IMF, WTO, and World Bank member states also reject the Washington Consensus, here looking at the EU in particular, is only another clear indicator: at issue is not Venezuela’s failure to adopt neoliberal policies proposed for it, but rather the US’s inability to adapt to the growing multipolar geo-economic system based in the growth of the world’s physical economy.

This obstinate position by Washington-Wall Street, and the City of London indeed only reflects that it has continued under certain illusions for four and a half decades. The US has relied heavily on its transnational and supranational influence, dominance over multilateral financial institutions and multinational corporations, using a welfare-subsidy system to bolster its private-co-public synergistic military industrial complex, which in turn acts as a global guarantor of its nominal economic dominance and ‘supply-chain security’, sometimes more clear when referred to as its ‘gunboat diplomacy’.

It has held onto these illusions at the institutional level through the formal regimes, even while it has abandoned the informal ones established at Bretton Woods, a framework whose stated aims have long since been usurped by the neoliberal Washington consensus.

For these reasons there has been a growing call for a new Bretton Woods agreement, one that would take into account the decline of the dollar and instead restore fixed rates, but this time based upon a basket of reserve currencies representing the multipolar economy. Maynard Keynes who was the key British negotiator at Bretton Woods and of the formation of what would become the IMF and World Bank, was critical of its establishment on the basis of the USD as the sole exchange and reserve currency and had proposed an ICU, many functions of which were ultimately filled at first on a dollar-basis through the IMF, but also with the eventual problems that he predicted. The inherent problem in the IMF was, as he pointed out, that as soon after the US lost its trade surplus, the coherency of the USD as the reserve currency within the informal regime, would dissolve with it. As the physical economies in the developing world indeed developed, this trade surplus would naturally evaporate, as Keynes predicted and as indeed happened.