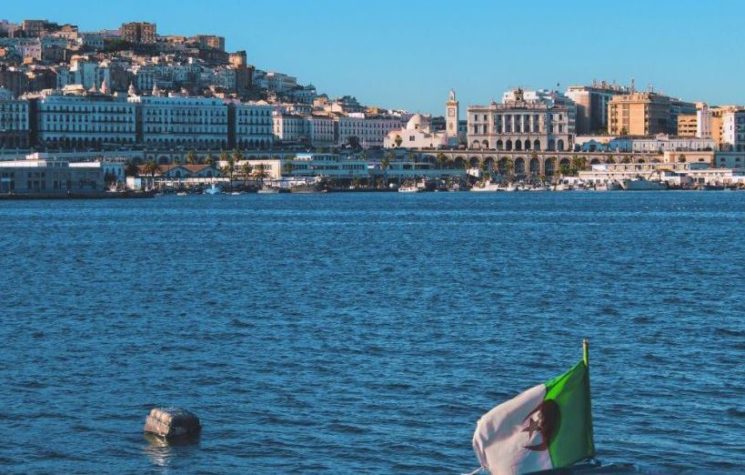

A massive shift in the geo-political status quo in North Africa has placed the United States in the passenger’s, not the pilot’s, seat. No longer does Washington, not even as a co-pilot with the French, influence the actions of key actors in North African affairs. The shift in the North African chessboard is the result of three recent major events. They are the resignation of Algeria’s ailing 82-year old president, Abdelaziz Bouteflika, who was about to begin his fifth term as president when massive protests led to his decision to step down. Bouteflika had served as president since 1999, the overthrow of Sudan’s President Omar al-Bashir, and the imminent fall of the Libyan government in Tripoli.

The Algerian military had originally seized power in 1992 after it was apparent that an Islamist party, the Islamic Salvation Front, would win a democratic election. Bouteflika assumed control of a “National Reconciliation” government in 1999, which was, in reality, a front for the military. Bouteflika had been on the Algerian political scene the 1970s, when he served as Algeria’s globetrotting foreign minister. Bouteflika’s resignation spelled the end of the rule of Algeria’s independence-era “old guard” – the “four Bs of Bouteflika, Ahmed Ben Bella, Houari Boumediene, and Chadli Bendjedid.

Bouteflika resigned on April 2, 2019. He was replaced by acting president Abdelkader Bensalah, the Chairman of the Council of State, who remains supported by the armed forces hierarchy, particularly, Algerian People’s National Army chief of staff Ahmed Gaid Salah, until a new presidential election is held this summer.

For the world, Bouteflika’s resignation represented a sea change for the resource-rich North African nation. When Bouteflika was Algeria’s foreign minister in the 1970s, his foreign interlocutors included US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko, British Foreign Secretary James Callaghan, Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai, and Egyptian Foreign Minister Boutros Boutros-Ghali.

In Sudan, President Bashir, who had served as Sudan’s president since 1989, was toppled by a military coup that followed mass pro-democracy protests. Even though Bashir resigned, he still has hanging over his head an indictment for crimes against humanity in Darfur, which were brought by the International Criminal Court in The Hague. The coup against Bashir was led by his own Vice President and Defense Minister, Lieutenant General Ahmed Awad Ibn Auf, who announced the creation of a textbook Transitional Military Council. The council invited the opposition and protesters to form a civilian government.

Protesters have not left the streets of Khartoum and other major Sudanese cities. Many recently turned out in force to protest an offer of $3 billion in assistance to Sudan from Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Many protesters told the Saudis and Emiratis to keep their money. They recalled that Bashir was a longtime recipient of assistance from Riyadh, Abu Dhabi, and Dubai and they do not want to see one president with puppet strings to the Saudis and Emiratis replaced by another.

In Libya, forces of the rebel “Tobruk Government,” led by a one-time Central Intelligence Agency asset and US citizen, “Field Marshal” Khalifa Hifter, commander of the Libyan National Army, stood at the outskirts of the capital, Tripoli, after conquering most of the country, including the eastern province of Cyrenaica, the southern region of Fezzan, and most of the western province of Tripolitania. In 1987, Hifter became a prisoner of war of Chadian forces after Libya’s unsuccessful military invasion of Chad. In 1990, Hifter decided to go to work for the CIA and he spent almost twenty years in Falls Church and Vienna in northern Virginia, near CIA headquarters, and was involved in various US plots against Libyan leader Muammar Qaddafi.

After the outbreak of the US-, NATO-, and Israeli-supported rebel uprising against Qaddafi in 2011, Hifter assumed command of the rebel Libyan Army. In 2017, Hifter’s forces took control of Benghazi. HIfter took aim at the Government of National Accord, the United Nations-recognized government based in Tripoli. Hifter has been called a war lord and he his forces have been accused of carrying out war crimes in Libya. Hifter is supported by Saudi Arabia, Egypt, the UAE, Israel, and the Abu Dhabi-based mercenary army of Blackwater founder Erik Prince. It is believed by many informed observers that Prince is an interlocutor between Hifter and the Israelis.

Although the US formally recognized the Tripoli government of Prime Minister Fayez al-Sarraj, Donald Trump called Hifter in mid-April offering him praise and support. Trump’s encouraging words to Hifter, who he glowingly referred to as “Field Marshal,” came after Secretary of State Mike Pompeo requested Hifter and his forces to “stand down” and begin negotiations with the Sarraj-led government for a peaceful resolution to the Libyan civil war. Trump’s unconditional support for Hifter also came after Trump’s White House meeting with Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, a major ally of the “Field Marshal.”

Some outside players are not keen on Hifter being in control in Libya. Turkey has been caught arming Libyan guerrilla groups opposed to Hifter, including groups linked to the Muslim Brotherhood and the Sarraj government. While Morocco is seen as backing the Tripoli government, Tunisia has been accused of supporting Hifter.

Hifter, who once tried to invade Chad on behalf of Qaddafi, is seen as potentially bringing Chad and its president, Idriss Deby, into his orbit. For that reason, Qatar, which does not want to see Chad fall under Saudi and Emirati influence, is backing a Chadian guerrilla force led by Deby’s nephew, Timan Erdimi, who is attempting to oust Deby. Erdimi’s base of operations is the Borkou-Ennedi-Tibesti (BET) region along the Chadian-Libyan border, the same area where Hifter suffered his “Waterloo” in 1987.

An interesting point about the spelling of Hifter’s name. As with Qaddafi, whose name had more than thirty spelling variations, when Hifter first appeared on the scene after the outbreak of the rebellion against Qaddafi, news reports spelled his name as “Hifter.” It then dawned on the CIA that the spelling was outwardly similar to “Hitler.” The media, in unison and complying with the “groupthink” that is expected from them, began spelling the “Field Marshal’s” name as Haftar. This writer prefers to use the CIA’s original spelling of “Hifter,” regardless of whether it sounds like Hitler. The CIA should have thought about that before it hauled Hifter out of mothballs in northern Virginia and gave him his own army in Libya.