The American political scientist known for promoting the “end of history” fish tale following the collapse of the Soviet Union and the spread of Liberal-capitalist values around the world now appears to be angling for ways – wittingly or unwittingly – to curtail the freedom of speech.

Writing in The American Interest as the virtual crackdown on Alex Jones was underway, Fukuyama argued that the usual suspects of the social media universe – Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Apple, and all of their vast subterranean holdings – need to come clean by entering a two-step rehabilitation program where they must: (1.) “accept the fact that they are media companies with an obligation to curate information on their platforms,” and (2.) “accept the fact that they need to get smaller.”

I think we can safely skip the “need to get smaller” suggestion with a hearty chuckle and focus our attention instead on the question of social media being held to the same rules as those that regulate America’s squeaky clean media divas, like The Washington Post, CNN and MSNBC.

The social media monsters argue that since they do not create original content, but rather mindlessly provide the clean slate, as it were, for third-party developers to post their own thoughts, opinions, news and of course wild-eyed ‘conspiracy theories,’ they cannot be bound by the same rules and regulations as the mainstream media, which must bear ultimate responsibility for its increasingly damaged goods.

“We’re not a media company,” the late Steve Jobs of Apple fame told Esquire in a rough and tumble interview. “We don’t own media. We don’t own music. We don’t own films or television. We’re not a media company. We’re just Apple.” On that note, Jobs reached over and switched off the interviewer’s tape recorder, bringing an abrupt end to the strained conversation.

Thanks to the provisions laid out in Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996, the social media platforms are granted immunity from liability for users of an "interactive computer service" who publish information provided by third-party users.

The act was overwhelmingly supported by Congress following the verdict in the 1995 court case, Stratton Oakmont, Inc. v. Prodigy Services Co., which suggested that internet service providers that assumed an editorial role with regards to client content thus became publishers and legally vulnerable for any wrongdoing (libel and slander, for example) committed by their customers. At the time, when alternative voices on the social media frontier had not turned into actual competition for the legacy media, legislators deemed it more important to protect service providers from criminal proceedings than to nip freedom of speech in the bud. Honorable? Yes. But I wonder if they’d have made the same decision knowing the powerful forces they had unleashed.

At this point, Fukuyama summarizes the plight regarding the social media platforms with relation to their independent creators, who wish to express their freedom of speech.

“Section 230 was put in place both to protect freedom of speech and to promote growth and innovation in the tech sector. Both users and general publics were happy with this outcome for the next couple of decades, as social media appeared and masses of people gravitated to platforms like Facebook and Twitter for information and communication. But these views began to change dramatically following the 2016 elections in the United States and Britain, and subsequent revelations both of Russian meddling in the United States and other countries, and of the weaponization of social media by far-Right actors like Alex Jones.”

Despite being a learned and intelligent man, Fukuyama jumps headfirst into the shallow end of a pool known as ‘Blame Russia’, while, at the same time, blames the far-Right for the “weaponization” of social media, as though the Left isn’t equally up to the challenge of waging dirty tricks, in a crucial election year, no less.

Next, he genuflects before the Almighty Algorythm, the godhead of Silicon Valley’s Valhalla, which, as the argument goes, was responsible for attracting huge audiences to particular channels and their messages, instead of the other way around.

“Their business model was built on clicks and virality, which led them to tune their algorithms in ways that actively encouraged conspiracy theories, personal abuse, and other content that was most likely to generate user interaction,” Fukuyama surmises. “This was the opposite of the public broadcasting ideal, which (as defined, for example, by the Council of Europe) privileged material deemed in the broad public interest.”

In other words, had Mark Zuckerberg and friends not toggled their algorithmic settings to ‘conspiracy theories,’ then the easily manipulated masses would never have given a second thought to well-known catastrophes based on pure and unadulterated evil, like the Invasion of Iraq in 2003, which, as the tin-foil-hat crowd constantly crows, was made possible by the fake news of weapons of mass destruction.

Here, Fukuyama lays on thick his extra-nutty academic drivel: “This is the most important sense in which the big internet platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube have become media companies: They craft algorithms that determine what their users’ limited attention will focus on, driven (at least up to now) not by any broad vision of public responsibility but rather by profit maximization, which leads them to privilege virality.”

In other words, internet users are not inquisitive creatures by nature with fully functioning frontal lobe regions like the honorable Francis Fukuyama. They do not actively search out subjects of interest with critical reasoning skills and ponder cause and effect. And let’s not even mention the mainstream media’s disastrous coverage of current events, which led to the alienation of mainstream audiences in the first place. In Fukuyama’s matrix, otherwise normal people subscribe to ‘alternative facts’ or conspiracy theories because those damn algorithms kept popping up!

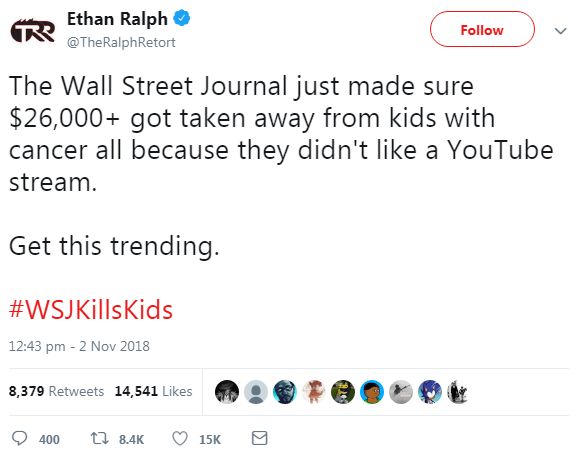

This ‘more righteous than thou’ attitude on the part of left-leaning Silicon Valley prompted hundreds of independent channels – the overwhelming majority from the right – to be swept away by a force known as ‘private ownership’ where brutal censorship has become the latest fad. Fukuyama, serving as the mouthpiece for both corporate and political interests, shrugs off this noxious phenomenon by arguing: “Private actors can and do censor material all the time, and the platforms in question are not acting on behalf of the U.S. government.”

Let’s give Fukuyama the benefit of the doubt. Maybe there really is no cooperation between the most powerful and influential industries for manipulating public opinion and the U.S. government. Yet we would do well to keep in mind some key facts that strongly suggest otherwise. During the two-term presidency of Barack Obama (2009-2016), Google executives met on average once a week in the White House with government officials. According to the Campaign for Accountability, 169 Google employees met with 182 government officials at least 427 times, a Beltway record for such chumminess. What is so potentially disastrous about such meetings is that Google, the chokepoint on news and information, which has the power to actually rewrite history, is fiercely Liberal in its political outlook as some whistleblowers who escaped the well-manicured campus known for employee neck massages and free lunches. What was discussed in the White House? Nobody really knows. However, there is already a treasure trove of publicly available information detailing the intimate relationship between US intelligence and Google (as well as the other usual suspects).

Fukuyama tries to conclude with an upbeat, happy message by saying “private sector actors…have a responsibility to help maintain the health of [America’s democratic] political system.” However, judging by everything in the article that preceded that remark, I would have to guess Francis Fukuyama would fully support yet more intolerance in the world of social media as a means of preserving America’s freedom-squashing status quo.