See Part I

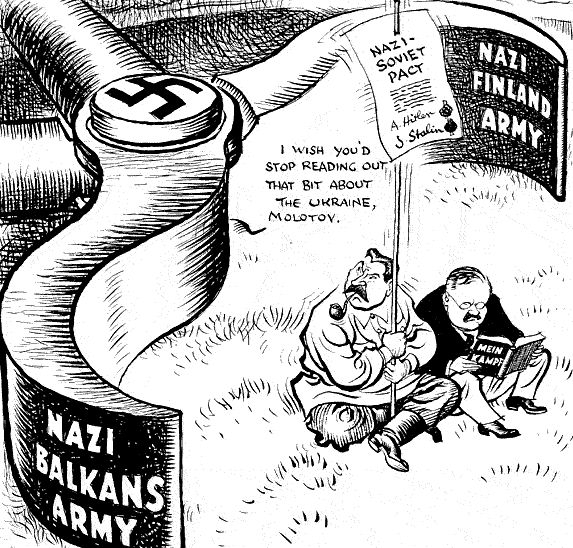

While MSM lays the blame on Stalin’s «alliance» with Hitler for starting World War II, it takes the opposite tack in the fighting of the war by ignoring the Soviet role in destroying Nazi Germany. The Red Army is practically invisible.

On 22 June 1941, more than 3 million German soldiers invaded the Soviet Union on a front stretching from the Baltic to the Black Seas. The Red Army was caught flat-footed largely because Stalin would not believe his own intelligence reports which accurately warned of the German invasion. Stalin invited one particularly valuable Soviet agent in Berlin to «go f*** his mother» («…Mozhet poslat' … 'istochnik' … k *** materi») when he warned that invasion was imminent. It was an open secret in Europe that Hitler would attack the Soviet Union.

Stalin seems to have been the only government leader not to believe it. US and British intelligence reckoned that the Red Army could not hold out for more than three or four weeks. That was the German estimate too.

During the first six months of fighting the Red Army lost three million soldiers; 177 divisions had to be written out of the Soviet order of battle. But instead of quitting after three or four weeks, as expected, the Red Army kept fighting through thick and thin, in spite of unimaginable catastrophes, the worst of which was the fall of Kiev in September 1941. To add to the horrors, the Germans sent in einsatzgruppen, death squads, to kill communists, Jews, Soviet officials, intellectuals, or anyone who got in their way. Women were stripped naked and forced to queue while waiting be to shot. Ukrainian and Baltic collaborators lent a hand. Hundreds of thousands, then millions of Soviet civilians died.

Yet the war was no walk in the park for the Wehrmacht.

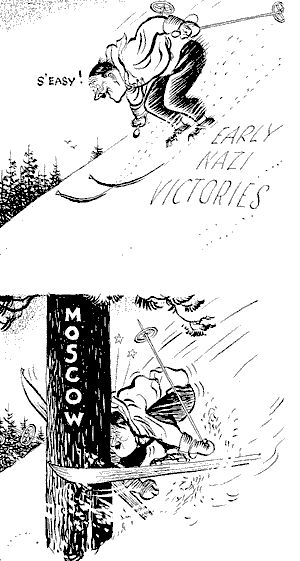

It made large territorial gains but at the loss of an estimated 7,000 casualties a day. This was a new experience for the Germans who until then had destroyed every adversary they faced with relatively little loss to themselves. Poland was essentially beaten in four days; France, in six. The British army was run out of Europe, first at Dunkirk, where it left all its arms, and then in Greece and Crete which were fresh British fiascos. There were also others later on in North Africa. The Wehrmacht was finally beaten at the battle of Moscow in December 1941, long after British and US intelligence said the war in the east would be over. It was the first time the Wehrmacht had suffered a strategic defeat.

Blitzkrieg against the USSR had failed.

The British were happy to have a fighting ally who didn’t after all surrender in three or four weeks. Churchill broke out cigars and cognac when he got the news of the German invasion and made an inspiring speech on BBC. But in that summer of 1941 the British government hesitated to call the Soviet Union «ally» and Churchill was adamant that BBC would not play the Soviet national anthem, the Internationale, on Sunday evenings with those of other British allies. Churchill only relented on this point after the battle of Moscow.

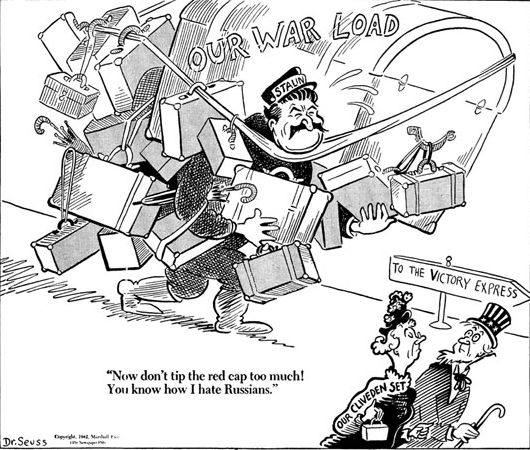

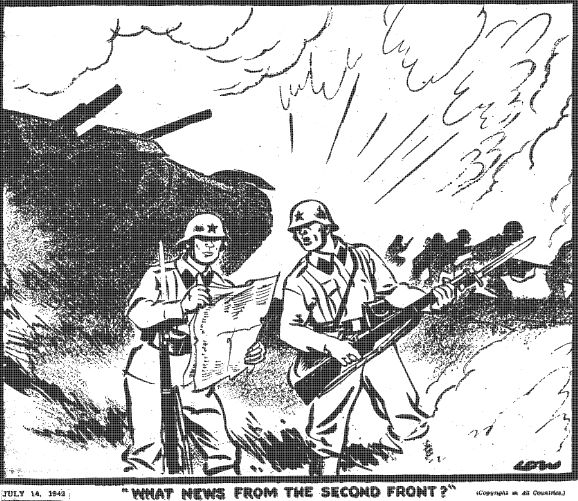

1942 was another year of sorrow and sacrifice for the Soviet Union. Everyone knew that the Red Army was carrying the main burden of the war against Germany.

In the autumn Soviet forces fought with their backs against the Volga in Stalingrad. Someone said Stalingrad was Hell. «No, no», another replied, «it was ten times worse than Hell». The Red Army won this ferocious battle, and the last German soldiers surrendered on 3 February 1943, fifteen months before the Normandy landings in France. On that date there was not a single US or British division fighting on the ground in Europe, not one. In March 1943 the tally of German and Axis casualties was enormous: 68 German, 19 Romanian, 10 Hungarian and 10 Italian divisions were mauled or destroyed. That represented 43% of Axis forces in the east. Many historians and contemporaries from clerks in the British Foreign Office to President Franklin Roosevelt in Washington thought that Stalingrad marked the turning of the tide of war against Hitler.

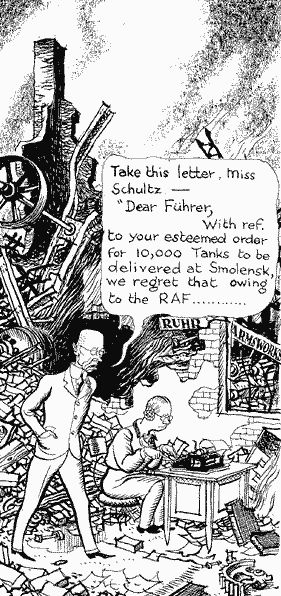

You won’t read much about all this in MSM, though some historians in the west have gotten the story right. MSM will tell you that the Red Army could not have defeated the Wehrmacht without US Lend Lease worth billions of dollars. What MSM will not say is that most Lend Lease arrived only after Stalingrad where Hitler’s fate had been sealed. They won’t tell you either that already in 1942 Soviet industry was out-producing Nazi Germany in various categories of armaments, long before Lend Lease supplies began to make a difference. The United States paid the price of war in Studebaker trucks and aluminium, and ogromnoe spasibo, thank you very much, Russians replied, but the Soviet Union paid in rivers of blood and tears.

The British government tried to convince public opinion, which understood the importance of the Red Army fight against Hitler, that it was doing something to contribute to the common cause.

This was the «strategic bombing» of Germany, though it was not very strategic or accurate either. A British study indicated that one bomber out of three came within 8-9 kilometres of hitting its target. So the British and Americans started bombing cities and killing large numbers of civilians. In raids on Hamburg in 1943, for example, they killed 40,000 people. Berlin was also hit with increasing loss to the civilian population.

Well, I guess that was worth something in terms of Red Army morale.

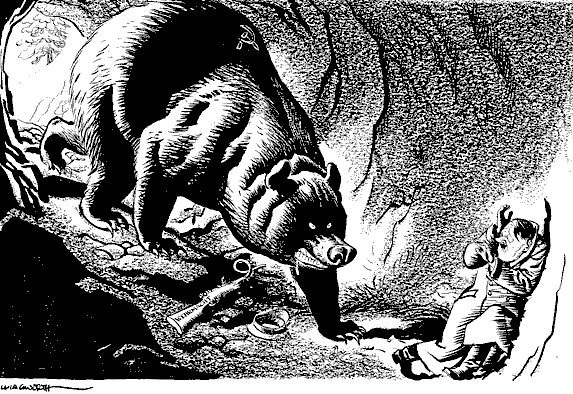

By mid-1943, Red Army morale was just fine. In July the battle of Kursk marked the beginning of a great counter-offensive which led to the liberation of Kiev and further north Smolensk in the autumn of 1943. The Wehrmacht was kaiuk, finished, a year before the Normandy landings. The Red Army became an unstoppable juggernaut. Na zapad!, to the west, was its war cry.

What Stalin really wanted was a second front in France.

The Americans and British made promises which they could not or would not keep. Churchill was schizophrenic about the Soviet Union, sometimes he considered it an ally; at other times, he called the Russians «barbarians» and Bolsheviks who had to be kept out of Eastern and Central Europe. His idea was to invade Italy (September 1943), not France, move quickly north up the Italian boot, then pivot eastward to keep the Red Army out of the Balkans. It seemed like a great idea on paper, but in reality, it was a flop. Allied forces didn’t get to Rome until June 1944. Italy proved to be a drag on Allied resources, more than it did on the Wehrmacht. Stalin kept pressing for a real second front in France, the shortest route into the German heartland, and he finally got a real commitment for it at the Teheran conference in the autumn 1943. This was Operation Overlord.

Of course, if you live in the west, the Normandy landings were the crucial event of World War II which sealed Hitler’s fate. Everyone in the west has heard of Operation Overlord, but just ask a class of university students, as I do, if they have ever heard of Operation Bagration which started two weeks later. Instead of students’ raised hands to signal knowledge of Bagration, I get puzzled looks. While the western Allies were cooped up in the Normandy pocket, the Red Army smashed the centre of German lines in the east and advanced in a matter of weeks some 500 kilometres to the west. German propagandists denied the gravity of the Wehrmacht’s defeat, and so to mock them, the Red Army marched 57,000 German POWs, part of the Bagration harvest, through the streets of Moscow in July 1944. It was the only way Germans could see the Soviet capital.

Ken Burns, the skilled American documentary film maker, declared in The War, about the US experience of World War II, that «without American power and without the sacrifice of American lives, the outcome of the struggle in Europe would have been very different». This is true, though perhaps not in the sense that Burns intended. Without «American power», the Red Army would have had the honour of planting its red battle flags on the Normandy beaches, liberating all of Europe with the support of anti-fascist resistance movements. This was just the outcome that Churchill, for one, was determined to avoid.

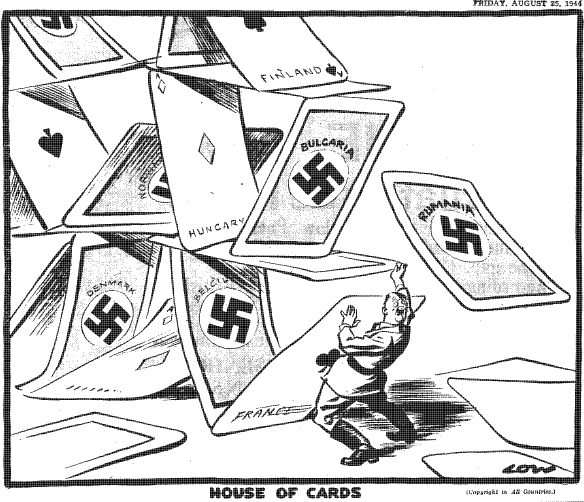

After Overlord and Bagration, it was only a matter of time before Nazi Germany collapsed, and everyone knew it.

The stronger the certainty of victory over Nazism, the weaker became the Grand Alliance against it. Roosevelt died in April 1945 and within a fortnight US policy began to shift toward anti-Soviet hostility. In London Churchill asked his Russophobic generals for a war plan against the Soviet Union. It was to be American and British forces, stiffened by German divisions presumably without Nazi insignia, which would confront the Red Army. A top secret document was actually drafted, «Operation Unthinkable», the first version of which was circulated a fortnight after VE Day. «The overall or political object», Churchill’s generals wrote, «is to impose upon Russia the will of the United States and British Empire». The Russians might «submit to our will» or they might not, but «if they want total war, they are in a position to have it». Oh my, what boasting. The plan was half-baked, unworkable, and utterly reprehensible. Eventually, it was shelved. «Unthinkable» marked the beginning of what would become a public campaign which has continued to this day to transfer the war’s origins to Stalin’s responsibility and to render imperceptible the Red Army role in destroying the Wehrmacht. Just consult any western poll of who «won» World War II. In the west most people think it was the Americans. This distortion of reality helps to assure the misgivings of some Eastern Europeans who appear to think that the war against Nazi Germany was a horrible mistake. If only Hitler had not been so unreasonable.

In some ways, nothing has changed since 1945: the United States and its loyal amanuensis Britain are still trying to impose their will on Russia. General Buck Turgidson-Breedlove, a contemporary Dr Strangelove and commander of NATO forces in Europe, said only a few weeks ago that NATO was ready «to fight and win» a war against Russia. It sounds like «Unthinkable» all over again. The European parliament and the OSCE are in the forefront of propaganda depicting Stalin as the chief associate of Hitler in setting off World War II. Remember Stalin, forget the Red Army is the West’s main strategy for transforming the history of World War II into a Russophobic narrative. You can understand why the West pursues this strategy; the real history of the origins and conduct of World War II does not fit into the fairy story of the western lamb and the Soviet wolf. The victory of the Red Army and Soviet peoples over Nazi Germany is so remarkable and so inspiring that even the multifarious, well-funded efforts of three generations of western propagandists have been unable to efface it. And they never will…