On 22 July, the Chinese press reported that the Chinese People’s Liberation Army is carrying out ten days of manoeuvres in the waters off the eastern island of Hainan in the South China Sea. China’s Maritime Safety Administration has stated that during the exercises, «no vessel is allowed to enter the designated maritime areas».

Commenting on the event, Xu Liping, an expert on Southeast Asian affairs at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, noted that China is carrying out the training exercises legitimately within its territory and they have «nothing to do with the tension in the South China Sea… It is a normal exercise of sovereignty. China wants to modernise its navy to make sure it has the capability to protect its islands and waterway».

Shortly before the exercises, meanwhile, the new commander of the US Pacific Fleet, Admiral Scott Swift, carried out a seven-hour surveillance flight over the South China Sea. On Monday 20 July, China’s Ministry of Defence expressed its opposition to America’s frequent surveillance missions that it believes are too close to China’s borders and seriously undermining Sino-US trust. The old debate about who owns the region’s islands has become a hot topic in numerous political publications once more, especially in the US.

Why is the subject, which is sensitive for many Southeast Asian countries, being actively stirred up once again and the situation being inflamed, primarily through the military presence of a country thousands of kilometres away? The US carried out a series of naval exercises in the region in 2015 and intends to carry out several more soon. Obama’s «Pacific axis», which has resulted in the redeployment of a significant proportion of the US Navy to the region, as well as the Marine Corps and Air Force stationed at bases in countries that are allies of Washington, is also directly related to China’s maritime strategy and the creation of logistics posts on previously barren reefs and rocky islets.

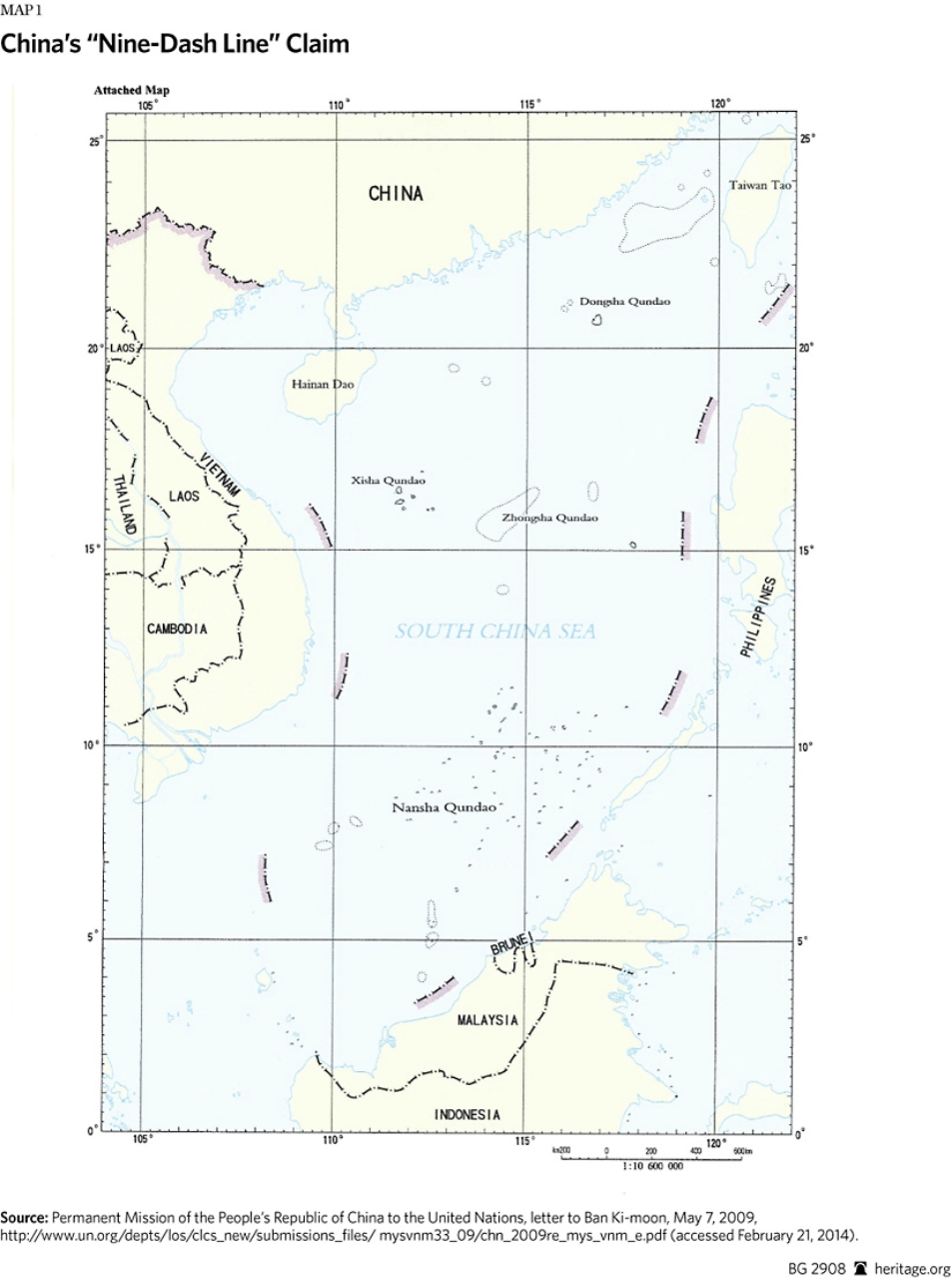

The fact is that in April 2015, Beijing successfully completed the construction of infrastructure on an artificial island in the Spratly Islands, thus virtually designating the previously uninhabitable area its sovereign zone. China declared its right to these islands in an official address to the UN Secretary General back in May 2009 and its intentions are obvious. With its growing economy and increasing energy and raw material exports shipped through the Malacca Strait, Beijing needs to create strongholds in the sea to insure against possible risks. The «string of pearls» strategy, also referred to as the water-based alternative to the Great Silk Road, is meant to solve the problem by repeating the historical experience of many other countries, including Great Britain and the United States.

On the issue of the islands’ ownership, Beijing, along with other regional players, has made use of the ancient law of Terra Incognita in the assimilation of these territories.

On Gaven reef, for example, an island has literally grown up out of the water over the past year and a half or so.

Modern technological infrastructure answering the logistical needs of such a large country as China has also appeared on other reefs.

Nevertheless, it is obvious that the US has no intention of allowing China to strengthen its strongholds and is getting ready to oppose it using military force. This is expected to involve not just the US Navy and Air Force (in accordance with an approved strategy for a possible war with China called «Air-Sea Battle»), but also the US Army. In the guidelines for the US Army’s Strategy in Asia 2030-2040 published in 2014 by the RAND Corporation, it says that America’s military strategy should be aimed at the comprehensive containment of China, including with the involvement of America’s regional partners.

The Pentagon has mapped out a special Southeast Asia Maritime Security Initiative, on which it is planning to spend $425 million. Washington is also encouraging the development of bilateral relations between its satellites for the purposes of opposing China. An example is the joint declaration and a number of other documents signed between the Philippines and Japan on 4 June 2015 reflecting not just the intention of both sides to join forces in the face of new challenges, but also to help the US in every way possible, including providing access to its bases and appropriate security.

Some experts believe that the US is weak and is acting reactively, while China is using a window of opportunity and is allegedly behaving aggressively by carrying out a policy of expansionism. They are calling on the US to recruit Japan, Indonesia, Australia and India to stand against China. Although they have nothing to do with the disputes in the South China Sea, they surround the region from the outside and are major players in their own right. The Pentagon is also increasing its presence on the territories of all its partners in the region – Singapore, Australia, South Korea, Japan, the Philippines, Indonesia, Taiwan and the island of Guam (there is also a British base in Brunei).

Objective facts show, however, that China is merely a scapegoat, a role it has been given with a helping hand from the West and the world’s media. According to a publication specialising in international relations in the Asia-Pacific Region, China is far from the only country that has unilaterally marked its territory among the Spratly Islands.

Vietnam occupies 21 features, five of which are natural islands and the rest rocks or sand banks. Of these, 17 have territorial status. The so-called Southwest Cay was seized from the Philippines in 1975 and the Philippines now own nine, one of which is an underwater reef. There were also plans to upgrade the airstrip on Thitu Island. In 2014, seeing how quickly China was erecting a number of facilities, the Philippines called for a moratorium on construction in the South China Sea. In 1983, Malaysia seized five islands while Taiwan seized just one – Itu Aba – investing $100 million to restore the infrastructure of the port and the airstrip and placing armed forces there. Work was fully completed on the island in February 2015. There is also Brunei, but, according to official data, it is only used as a platform for the extraction of oil and gas on the shelf of the South China Sea.

It is extremely telling that before 2014, when China began to construct a 3 km airstrip on Fiery Cross Reef in the southern part of the Spratly Islands, Beijing did not have an airstrip on the islands at all. Construction also began in 2014 on the southern Johnson South Reef. And so the Chinese are just repeating what other countries have already done, countries whose actions did not arouse the indignation of the US.

Incidentally, the Chinese have always stressed that they have no intention of carrying out any kind of aggressive actions in the South China Sea and hope that Obama is not planning any acts of provocation either.

However, the US is constantly pouring oil on the fire, not just through its military and intelligence-gathering operations, but rhetorically. Thus the US State Department, represented by the State Secretary and other representatives, have repeatedly stated that freedom of navigation in the South China Sea is in the national interest of the US, a statement that is painfully reminiscent of former US president Jimmy Carter’s statement about the Persian Gulf in 1980, when he threatened to use military force if US interests were threatened.

At the same time, and with the cynicism typical of American politicians, the US is declaring that it does not need to ratify the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea to defend its national interests in the South China Sea. Although according to its action plan in the region, Washington will support any lawsuits against China in the arbitration courts.

If you bear in mind that 60 per cent of world trade traffic passes through the region, as well as Washington’s continuing attempts to promote its Trans-Pacific Partnership project, then it is unlikely that the US will stop its acts of provocation and China will be left with no choice but to strengthen its security.