Military activity in the Arctic region is steadily increasing; this is undeniable and now evident to all.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

American Security Challenges

With the expansion of access to the Arctic region, new threats are emerging that are forcing Arctic states to step up their investments in safeguarding their strategic and economic interests. Historically, the U.S. military and security position has focused on the North American Arctic, due to Alaska’s integration with economic activities in the Bering Sea and the air and underground threats identified in that area.

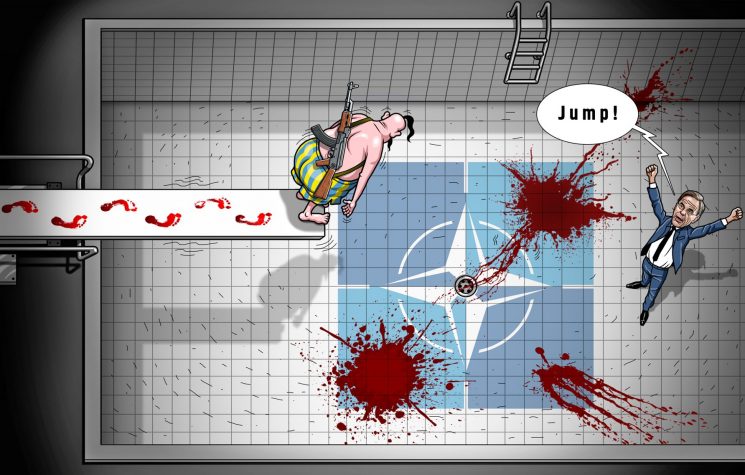

The national defense concerns of the European Arctic states and their respective investments stem primarily from their geographical proximity to the Russian Federation. Sweden and Finland’s accession to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization has further expanded the collective defense obligations of the Alliance’s Arctic members in the event of conflict. In addition, the U.S. Department of Defense views China’s growing presence in the Arctic as a potential destabilising factor.

Furthermore, the expected increase in commercial activity in the Central Arctic Ocean (CAO), as outlined in the previous analysis, is likely to generate a corresponding growth in government operations aimed at ensuring the safety and security of populations, assets and critical infrastructure. Such efforts will necessarily include the enforcement of governance frameworks and the maintenance of a rules-based international order, with a particular focus on maritime law enforcement, environmental protection, search and rescue (SAR) operations, and the safeguarding of subsea infrastructure. The following discussion identifies the main drivers and obstacles to the expansion of security-related activities in the CAO, drawing on publicly available academic research, policy documents, and strategic publications from Arctic states and China.

Issues related to the laws of the sea

It is expected that increased accessibility to the Arctic Ocean will be accompanied by a parallel increase in illicit maritime activities, mirroring phenomena observed in other regions of the world, such as smuggling, transnational crime, and terrorism. The likely consequence of these developments will be an increased presence of coast guards and equivalent law enforcement agencies operating in Arctic waters.

Arctic sea routes could offer shorter transit routes to certain illegal markets than southern alternatives, while the harsh environmental conditions and remoteness of the region could reduce the risk of interception and boarding at sea. In addition, the intensification of commercial operations could increase vulnerability to acts of disruption, both non-violent and violent, by non-state actors seeking to undermine the economic interests of specific states or companies. Incidents such as Greenpeace’s obstruction of a Russian oil platform in the Arctic in 2013 demonstrate how even peaceful protests can jeopardize maritime security. More serious acts of sabotage would further justify the deployment of specialized law enforcement forces capable of responding quickly. If national governments decide to allocate more resources and funding to maritime control agencies, this would likely result in an increase in specially built ships capable of operating within exclusive economic zones (EEZs) and, possibly, within the CAO. However, such developments would be mitigated by the significant costs and construction times associated with polar vessels, as demonstrated by the prolonged efforts of the United States to expand its icebreaker fleet.

The implementation of regulations aimed at mitigating the risk of oil spills and other maritime accidents, such as those codified in the Polar Code, will also require an increased law enforcement presence. This will likely involve the use of manned and unmanned systems, including aerial drones and autonomous surface or underwater vehicles. However, advances in spatial domain awareness could reduce the physical footprint required for law enforcement, allowing for the strategic concentration of resources in areas of high environmental risk or low compliance.

Another emerging area of concern is the protection of submarine communications cables. Several Arctic cables have suffered serious damage in recent years: those supporting scientific observation off the west coast of Norway and cables connecting Svalbard to mainland Norway were severed in November 2021 and January 2022, respectively. Such infrastructure is prone to breakage due to seismic activity, underwater landslides, ocean currents, or damage caused by anchors, whether accidental or intentional. Submarine cables laid within the CAO would enjoy some protection due to their depth and remoteness; however, these same factors complicate repair operations. Sea ice movement prevents repair vessels from maintaining a fixed position, while extreme depths may preclude the use of divers or remotely operated vehicles. Given the global importance of data transmission and the high cost of building redundant lines, these cables are attractive targets for sabotage, although robust security measures could serve as an effective deterrent.

A more hypothetical but potentially significant source of military activity in the Arctic concerns overlapping and unresolved claims relating to continental shelf extensions by Arctic states. Although the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf evaluates and makes recommendations on the scientific validity of such claims, the final delimitation of extended continental shelves remains a matter for negotiation between states. If this bilateral or multilateral process were to become protracted or contentious, particularly if the CLCS’s recommendations favored some claimants over others, tensions could escalate, leading to an increase in military or law enforcement presence in the CAO. Coastal states may attempt to conduct exclusive scientific exploration or authorize commercial exploitation in disputed areas, thereby increasing the risk of sabotage or retaliatory actions. However, such scenarios remain unlikely given the relative inaccessibility and limited economic interest of resources located deep in the CAO, especially in light of the abundant reserves already available in coastal regions. Historical precedents support this assessment: despite a 40-year dispute over the Barents Sea border, Norway and Russia refrained from drilling until a negotiated agreement was reached. Furthermore, any deviation from the procedures established by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) would undermine legal certainty and economic stability, an outcome that even the major Arctic powers, including Russia, have no interest in provoking.

The expected growth in freight transport, fishing, extractive industries, and tourism in and around the CAO will inevitably increase the risk of maritime accidents, including groundings, collisions, flooding, fires on board, and oil spills. This expansion of maritime activities will require a corresponding increase in search and rescue and disaster response capabilities. The challenging Arctic environment compounds these challenges.

The 2011 Agreement on Cooperation in Aeronautical and Maritime Search and Rescue in the Arctic divides the Arctic Ocean, including the CAO, into designated areas of responsibility, with the aim of improving communication, coordination, and response efficiency among participating states. Compliance with this framework, supported by adequate investment in infrastructure and equipment, should improve overall SAR preparedness. Complementary mechanisms, such as the voluntary automated mutual-assistance vessel rescue system, known as AMVER, could further strengthen coordination among maritime actors.

In contrast, the 2013 agreement on cooperation in preparing for and responding to marine oil pollution in the Arctic does not establish territorial areas of responsibility, but rather promotes cooperation, training, and joint exercises, activities that could increasingly take place within the CAO as the marginal ice zone continues to retreat northward. Advances in cold-weather battery technology could also facilitate the use of unmanned aerial or maritime systems in future SAR operations in the Arctic, particularly in hazardous or remote environments. Despite these developments, both search and rescue and disaster response in the CAO remain limited by persistent gaps in infrastructure and operational capacity.

Responding to presence with presence

Military activity in the Arctic region is steadily increasing; this is undeniable and now evident to all.

Between 2015 and 2023, Russian military exercises in the far north have intensified in frequency and gradually moved further north, from the Norwegian Sea to the Barents Sea, to reinforce the Northern Fleet’s bastioned defense strategy. At the same time, Western-led multinational exercises, many of which have involved non-Arctic nations, have also become more frequent. From 2006 to 2019, their number increased from one to four per year, and there have been moments of tension.

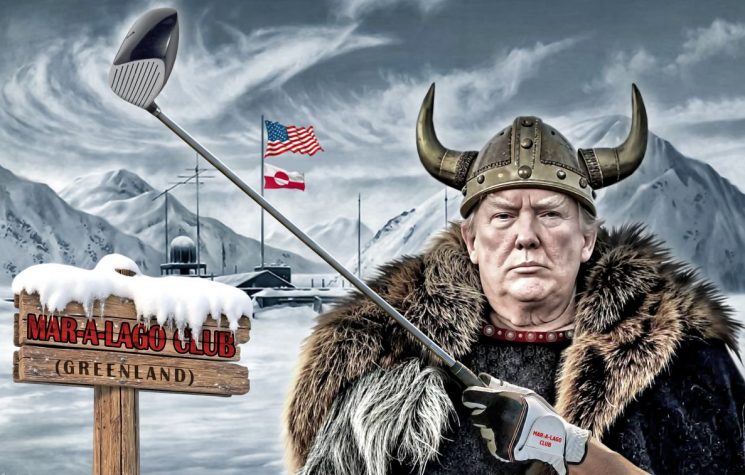

With commercial and security activities continuing to expand across the Arctic, states bordering the region are increasingly seeking to “respond to presence with presence,” ensuring that no single actor dominates the regional security environment. For the United States, one of the main incentives for increasing its operational presence has been the gradual increase in Chinese military and security activities in Arctic waters. On several occasions, Chinese warships have been observed transiting the Bering Sea. In October 2024, China and Russia conducted their first joint Arctic coast guard patrol, crossing the Bering Strait. In response, the U.S. Coast Guard deployed aircraft and patrol boats to monitor the ships of both nations. Although limited in scope, these operations signal Beijing’s determination to assert a visible presence in the Arctic and in proximity to U.S. territory. This is a fully American strategy, which is not difficult to adapt to a relatively new context.

China seeks to transform Arctic governance into a less exclusive regional framework, which would allow non-Arctic states to take on a more significant role. By maintaining a physical presence, China strengthens its claim to relevance as an Arctic stakeholder. This strategy is supported by growing logistical and operational capabilities: the People’s Liberation Army Navy has acquired the ability to conduct extended patrols abroad, facilitated by greater access to maintenance and supply infrastructure for Arctic missions, which the U.S. perceives as a constant threat. The deepening of the Sino-Russian strategic partnership, together with China’s substantial investments in Russia’s Arctic energy sector, has opened up access to Russian ports and related facilities. In the long term, with the continued expansion of China’s commercial interests in the region, particularly in the resource extraction and energy sectors, Beijing may seek to increase its maritime military presence to complement its diplomatic, scientific, and economic engagements with Arctic states.

The strategic positions of Arctic and sub-Arctic nations provide further insight into which states may intensify their presence in the Central Arctic Ocean to safeguard their commercial and security interests. Official strategies published by the United States, Canada, Finland, Norway, and Denmark often emphasize the importance of domain awareness and maintaining a stable, low-tension Arctic. The U.S. Department of Defense’s 2024 Arctic Strategy outlines a “monitor and respond approach,” stating that the Department “will remain capable of deploying Joint Force globally at a time and place of our choosing.” Similarly, the U.S. Coast Guard’s 2023 Arctic Strategic Outlook Implementation Plan calls for “increased presence, awareness, and understanding within the Arctic,” while reiterating adherence to international laws and norms. In contrast, Russia explicitly defines the Arctic as a critical area in which to consolidate and project its maritime power.

Beyond policy documents, sustained presence in the CAO depends on the capacity and ability of states to operate effectively in harsh polar conditions, particularly for those seeking to position themselves as early and influential actors as the region becomes more accessible. To do so, the U.S. needs significant investment and to speed up the process, because the gap with its adversaries is significant (Russia and China dominate the Arctic not only in terms of presence but also in terms of technology).

The high costs and technical specialization required for the production of ships capable of navigating through ice, combined with their limited versatility, underscore the value of cooperation and joint initiatives among Arctic states. In November 2024, the United States, Canada, and Finland signed a Trilateral Icebreaker Cooperation Agreement, establishing a framework for the exchange of technical knowledge, research, and development in order to “increase production and reduce the cost of Arctic and polar icebreakers.” At the same time, the U.S. Coast Guard and Navy are seeking to expand the national fleet with eight to ten medium and heavy icebreakers through the Polar Security Cutter and Arctic Security Cutter programs. For its part, Norway intends to acquire six 212CD submarines, a decision likely influenced by increased Russian submarine activity. The United States has Seawolf and Virginia class submarines capable of operating under Arctic ice, which participate in high-latitude exercises every year; the Navy’s Shipbuilding Plan for 2025 calls for a total of forty-five Virginia class submarines by 2054.

Other Arctic states have more limited submarine capabilities or capabilities unsuited to polar operations. Canada’s four Victoria-class submarines cannot operate under ice, while the Swedish fleet is optimized for operations in the Baltic Sea and Gulf of Bothnia rather than Arctic waters. Among non-Arctic countries, France and the United Kingdom both have nuclear-powered submarines equipped with ballistic missiles (SSBNs) and attack missiles (SSNs) capable of operating in the Arctic, while Portugal deployed a diesel-electric submarine to the Arctic in 2024. But none of this compares to the maritime power of Russia and China in the region. This disparity will sooner or later lead to a direct confrontation in the domain concerned.