Before the advent of Zionism, Judaism had no historical practice of expelling native populations, Bruna Frascolla writes.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

Reflecting on the Zionist version of ancient history, Shlomo Sand makes a very timely observation: “The Romans never practiced the systematic expulsion of any ‘people.’ It might be added that even the Assyrians and Babylonians never transferred the populations they had subdued. The expulsion of the ‘people of the land,’ producers of the agricultural food from which taxes were levied, was not profitable.” (The Invention of the Jewish People, chap. “The Year 70 of the Christian Era”) It was not customary among the Romans to expel native populations. Zionists, on the other hand, make history and even politics a succession of expulsions: Rome allegedly expelled the Jews (understood as a racial group), so now they have the right to expel the “Arabs” who are there. In reality, most Hebrews remained in Judea, but were converted to Christianity and later Arabized by the Islamic conquests (which imposed the new language and imposed taxes on the “religions of the book,” that is, Judaism and Christianity). Furthermore, the Hebrews who remained in Judaism and left Judea engaged in extensive proselytizing, so that descending from the Hebrews and being an adherent of Judaism rarely happens to the same person.

Before the advent of Zionism, Judaism had no historical practice of expelling native populations. In ancient times, the Hasmonean dynasty, when there was still a Jewish kingdom, forced subjugated peoples to convert—a far more dramatic practice than conversion to Christianity, since it included circumcision. Throughout the rest of Antiquity, the Middle Ages, and Modernity, Jews, whether in the West or the East, settled in communities within other nations, and there engaged in specific activities, usually linked to credit and trade. Among the many and diverse accusations leveled against them, one does not include taking up arms to expel residents and seize their homes.

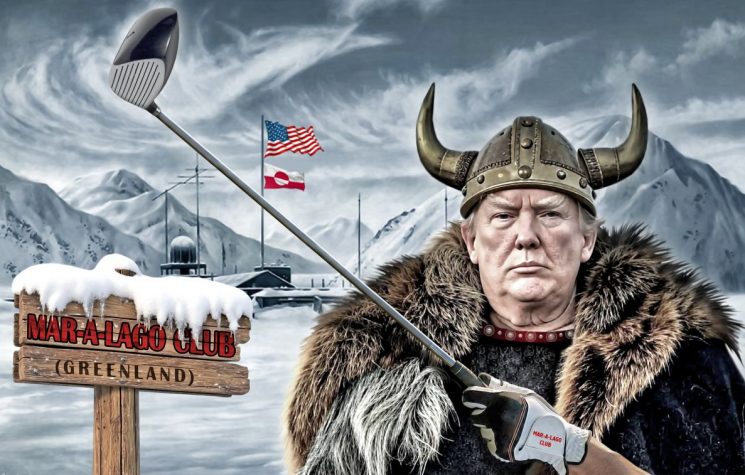

Among Jews, Zionism emerged as an Ashkenazi initiative. However, a very relevant earlier component is that of the English-speaking Calvinists, who were the first to envision a Jewish colonization of Palestine. England itself was a major sponsor of this endeavor. And if we look at their ethnic origins, the Angles, we see a very different history.

The Middle Ages were marked by barbarian invasions. These invasions were generally not accompanied by the expulsion of native populations. The usual process in Europe was one of sedentarization, partial acculturation, and miscegenation of the barbarians. Europe, by the Late Middle Ages, was no longer as Latin as before, but the barbarians were not untouched by the culture of the conquered: they became Christianized and civilized.

In present-day Denmark, there was a tribe with a different behavior: the Angles. From there, they set out to conquer the great island of Britain, then inhabited mostly by the Britons, a Christian Celtic-speaking people. (The Picts, ancestors of the Scots, were north of Hadrian’s Wall.) The legend of King Arthur revolves around this: he is the last British king, cornered in Cornwall, fights against the pagan invasion and attempts to reclaim Britain.

He fails. The Angles are joined by the Saxons, with whom they share Germanic ancestry, and mingles with them. Expelled, the Britons were squeezed into the west of the island, where Wales is today, or else fled to the mainland: they went to present-day Brittany, in France, and present-day Galicia, in Spain (where the Galician-Portuguese dialect emerged, giving rise to the language spoken by hundreds of millions in the Americas, Europe, Africa, and Asia). Roughly speaking, England is the land the Anglo-Saxons took from the Britons, and Wales is the area left over from ancient Roman Britain. All of this happened during the High Middle Ages.

In the Late Middle Ages, England returned to its Anglian roots during the Hundred Years’ War. In addition to its barbarity against peasant populations, its actions in Calais are worth highlighting: in 1347, after the English conquest, “the city was empty—its inhabitants were driven out, each with only a loaf of bread. All movable property was distributed as booty, and in England, all volunteers were called to repopulate Calais as colonists. Within weeks, two hundred people had come forward. The city became English territory for more than two centuries, ‘the key and lock that secure our way to France,’ the king declared.” (Georges Minois, La Guerre de Cent Ans, ch. 2)

The population replacement perpetrated by Ashkenazi Jews in British Palestine in 1948 resembles this, and nothing else that has happened in the history of Judaism. There is even a similarity in that the local domination was understood as a bridgehead for a broader domination.

There is a strong symbiosis between Calvinism and Judaism. Therefore, the atavism of one tribe (the Angles) ended up being covert and attributed to the ancient Hebrews.