The instability in southern Algeria remains an open chapter that will have to be seriously addressed.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

Another step forward

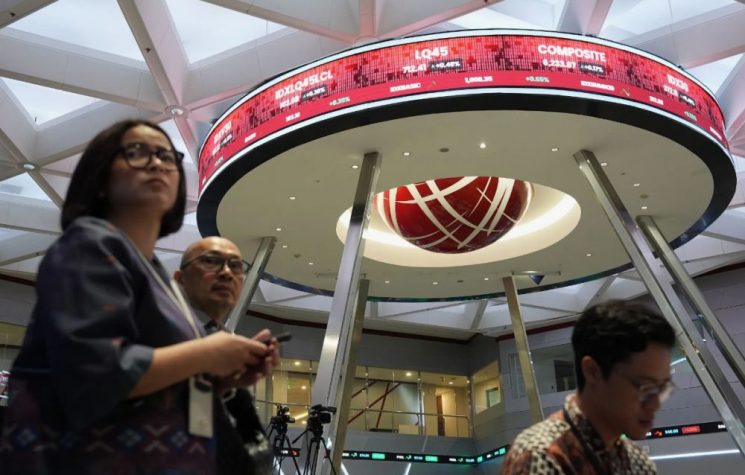

Another step forward for the Global South: Algeria has completed its accession to the BRICS New Development Bank, becoming a full member after its admission in September 2024.

This is a politically significant move, as it confirms the multipolar approach of the OPEC countries, most of which are new partners of the BRICS. Not only that, but this move is a blow to Western colonialist finance, as Algeria, a former French colony, is a country located in North Africa, a continent that is increasingly in the multipolar orbit and less and less in the Western one. This is a sign that should not be underestimated.

OPEC is made up of 13 countries: Algeria, Angola, the Republic of Congo, Guinea, Iran, Gabon, Iraq, Kuwait, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, Libya, the United Arab Emirates and Venezuela. It was founded on 14 September 1960 in Baghdad (the capital of Iraq) by five countries: Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and Venezuela. Over time, the number of members has increased. The countries belong to North, West, South and Central Africa, the Middle East and Latin America. Member states are able to influence oil prices, thereby gaining influence in the world. These countries are not part of the collective West, but are currently among Russia’s ‘friendly countries’, which places them in a latent confrontation with the West and OPEC, which, with the advent of BRICS, is changing dramatically.

Admission to the BRICS Bank requires, first and foremost, the promotion of sustainable and infrastructural development in emerging countries. The conditions for access are few but fundamental:

- Be a developing or emerging country

- Adhere to the Bank’s objectives and principles

- Contribute to the capital with a subscribed share of at least 100 billion (calculated in dollars)

- Adapt tax and financial transparency regulations

- Not be subject to serious international sanctions

Algeria has managed to meet the conditions for access and is now leading North Africa towards the geo-economic routes of the BRICS, which may also represent an important opportunity for other sub-Saharan African countries that are preparing to join. At the same time, however, there are a number of difficulties. Africa is an extremely complicated continent, steeped in multi-dimensional conflicts.

How Algeria got here

Algeria’s recent economic history is closely intertwined with the evolution of the energy sector, internal political dynamics, demographic pressures and the challenges posed by dependence on oil revenues. Since independence in 1962, the Algerian economy has followed a path marked by phases of statism, attempts at liberalisation and cyclical crises. However, in recent decades, from the 1990s to the present day, the country’s economic history has mainly reflected the difficult balance between abundant natural resources and a structural inability to diversify the economy.

In the 1990s, Algeria faced one of its most dramatic phases from a political and economic point of view. After the failure of the socialist and planned model adopted in previous decades, the country attempted a transition to a market economy under pressure from international institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF). During this period, important structural reforms were initiated, including trade liberalisation, the privatisation of some public enterprises and the reduction of state subsidies.

However, the Algerian civil war (1991-2002), triggered after the cancellation of elections won by the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS), had a devastating impact on the economy: the climate of violence and insecurity paralysed investment, trade and tourism, causing a contraction in GDP and an increase in unemployment, especially among young people.

With the end of the civil war and the arrival in power of Abdelaziz Bouteflika in 1999, Algeria entered a phase of relative political stability and economic growth thanks to rising hydrocarbon prices. The country is one of Africa’s leading producers of natural gas and oil, resources that account for about 95% of exports and more than 60% of state revenues.

During the 2000s, the government launched an ambitious public investment programme financed by energy revenues, called the Programme de soutien à la relance économique (PSRE), aimed at developing infrastructure, public housing, education and health. Algeria also managed to reduce its foreign debt and accumulate significant foreign exchange reserves.

However, despite this apparent prosperity, the Algerian economy remained heavily dependent on the energy sector and unable to create a competitive industrial or agricultural base. ‘Social containment’ policies — such as widespread subsidies and public employment — helped maintain stability but also entrenched a welfare-dependent and unproductive economy.

The collapse of oil prices in 2014 marked a critical turning point for the Algerian economy. State revenues fell sharply, putting pressure on the public budget and foreign exchange reserves. Faced with this crisis, the government avoided unpopular measures such as removing subsidies or drastically devaluing the currency, but was forced to reduce public investment and increase the fiscal deficit.

This period starkly highlighted the limitations of the Algerian economic model: lack of diversification, low private sector productivity, the weight of bureaucracy and the lack of attractiveness for foreign investment. The attempt to revive the economy through the ‘2015-2019 Five-Year Plan’ had limited impact.

2019 marked another turning point: a vast popular protest movement, known as Hirak, led to the resignation of Bouteflika after 20 years in power. This movement also expressed a rejection of the clientelist and inefficient economic system.

The new government, led by Abdelmadjid Tebboune, has announced several economic reforms, including the promotion of the agricultural sector, the development of SMEs, the fight against corruption and the attraction of foreign investment. The results have been modest so far.

The problem with the Confederation of Sahel States

Just as the Confederation of Sahel States is leading the battle for revenge against European colonialism in Africa, Algeria is facing difficulties with Mali. In recent years, the country has been dealing with the problem of Islamic fundamentalist terrorists, pushing them south into the Sahel, from where they have moved north following clashes with the Malian army.

Power in Algeria is largely controlled by a military elite whose main objective remains the preservation of the existing political order. Although reforms have been regularly announced, successive constitutions have often served to strengthen the army’s control over the state, neutralising opposition and marginalising regional identities. This excessive centralisation has led to a growing loss of confidence in institutions, particularly in peripheral areas.

Kabylia remains the nerve centre of opposition to the central authorities. Movements calling for autonomy, such as the MAK (Movement for the Self-Determination of Kabylia) led by Ferhat Mehenni, who is in exile abroad, are declared illegal and their supporters repressed. The persistent refusal to recognise the cultural, linguistic and political specificities of this region contributes to accentuating the break with the central power. In the long term, Kabylia could consider independence.

In the south of the country, the Tuareg, Mozabite and Saharan populations still live in very difficult socio-economic conditions. Despite the significant hydrocarbon wealth of these territories, they remain largely neglected in terms of development, heavily militarised and excluded from decision-making circles. Several movements, often clandestine or transnational, express separatist aspirations or even an explicit rejection of Algiers’ authority, which is a source of considerable concern for all regional partners.

The Polisario Front, based in Tindouf for several decades with the support of the Algerian authorities, remains a strategic ally of Algeria in the Western Sahara issue, particularly in the fight against Zionism and in its proximity to the Axis of Resistance.

The instability in southern Algeria remains an open chapter that will have to be seriously addressed, perhaps through the mediation of the BRICS, otherwise it will be impossible to reunify the multipolar African bloc. Everything in its own time. As an ancient Ethiopian proverb says, ‘If you pick up one end of the stick, you pick up the other’.