Only a tellurocracy that has fully realized its continental vocation can truly face the waves of the seas.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

The three seas of the world

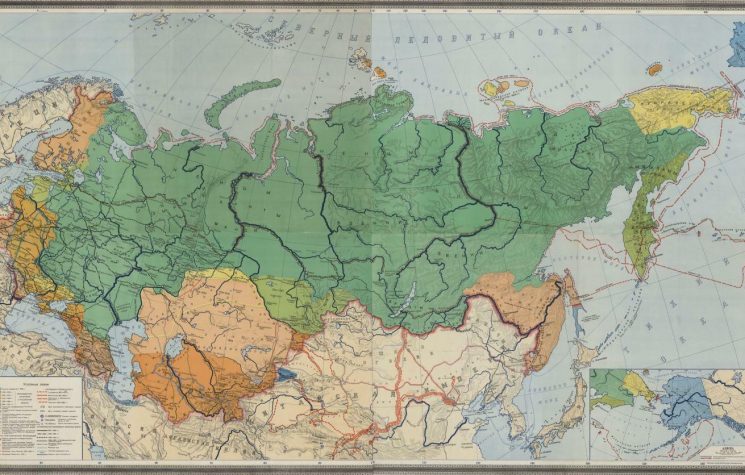

Russia, late 19th century: a highly decorated geographer, explorer, and statistician named Pyotr Petrovich Semenov Tjan Shansky established one of the most original definitions of nascent Russian geopolitics. For the adventurous researcher, Russia had to be read and understood as ‘what lies from sea to sea’, codifying an interesting interpretation of the geography of the then great Russian empire.

In a direct and coherent manner, he drew on the political geography and anthropogeography of Friedrich Ratzel, the great German ethnologist and geographer. Semënov, whose work On the Power of Territorial Possession in Relation to Russia can be considered one of the first fully-fledged geopolitical works in Russia, proposed his own hypothesis on the geopolitical structure of the world, which we can briefly summarize as follows: civilizations form around the three seas of the world, the Mediterranean (together with the Black Sea), the East and South China Seas (together with the Sea of Japan and the Yellow Sea), and the Caribbean basin (including the Gulf of Mexico). From these areas, culture spreads in different directions, eventually covering the entire planet, in different phases of history but linked to the three seas.

This gives rise to the theme of ‘power’: those who manage to establish political control over the entire coastline adjacent to one of the three seas of the world then gain dominion over all the adjacent territories.

No sooner said than done. This is not an assist to Halford Mackinder’s thalassocratic geopolitics, which he did not know, but a providentially specular reading, denoting an interest in the power of the seas on the part of Russia, at a time and in a context that make this topic extremely intriguing.

Throughout history, the consolidation of dominion over the seas has given rise to three specific configurations of ‘power of possession’, each corresponding to different coastal morphologies. In the context of the European Mediterranean, a ring-shaped model based on continuous coastal control has emerged. A second paradigm emerged during the colonial era in Western Europe, characterized by the establishment of fragmented forms of possession on archipelagos and disjointed portions of continental territory, scattered along ocean routes and interconnected by regular military and commercial shipping. This configuration was defined by Semënov as “leopard-spot.” The third model, developed by the same author, is the ‘sea-to-sea’ model, which can be traced back in the classical geopolitical tradition to the continental or telluric paradigm. This latter concept represented a crucial moment in the development of Russian geopolitical theory and, had the revolutionary events of 1917 and the imposition of Marxist-totalitarian ideology by the Bolshevik regime not interrupted its development, Semënov’s studies could have given rise to a veritable Russian school of political geography and geopolitics.

Russia, in all this, has a unique position: it is geographically surrounded by several seas and, due to its enormous size, has the ability to control and influence the development of several seas and the powers located there. This change of perspective allows us to view Russia from a thalassocratic point of view, not defining it as a primarily thalassocratic power, but in a secondary sense, as a sort of “indirect thalassocracy,” given its tellurocratic breadth.

Semënov historically concretized the cultural and economic bases of colonization, when, according to him, there were various bases of cultural and economic colonization in Russia. These focal points, spreading their light in all directions, truly maintain the strength of the state territory and contribute to its more uniform settlement as well as to its cultural and economic development. If we look at European Russia, we see four specific Russian areas that arose at different times: a first nucleus was formed in the area of Galicia and Kiev-Chernihiv; the second in the land of Novgorod and Petrograd, the third in Moscow, and the fourth in the Middle Volga. The nuclei in Galicia and Novgorod had to face Western enemies and went into complete decline for a long time, only to rise again like a phoenix from its ashes. The lands of Moscow and the Middle Volga, which occupied an internal geographical position, grew almost uninterruptedly, without experiencing long periods of decline. Thanks to these four cultural nuclei, the Russians were able to entrench themselves firmly within the coasts of the four seas, managing to become a world power.

His theory proved fundamental in dictating Russia’s Eurasianist line: having realized its continental nature and accepted its Eurasian character, Russia would look at the world and the processes developing in world politics with a completely new perspective.

Russia, therefore, was capable of managing three seas, or perhaps even more. A whole new perspective.

A lesson that still holds true

In a sense, Semënov’s lesson is still relevant today and, more than a theory, has become a fait accompli.

Russia has proven that it can manage the three seas, at least by protecting itself from attacks that could come through them.

The Mediterranean has become ‘distant’ in recent years due to sanctions and the West’s withdrawal, although it cannot be abandoned as a water basin representing an important source of resources and access to the Middle East and Africa. But it is also the sea of ancient trade, of the first and second Rome, of the millennial history of Europe from which part of the Russian people originate. It is an ethnosociologically indispensable area. Sooner or later, Russia will return to establish commercial or military dominance there.

The East China Sea has become an area of equilibrium with China and, in general, with the powers of the Far East. Russia has established a large part of its port market and fleet there, establishing important partnerships. The solid chain of allies in the region guarantees stability.

As for the Caribbean, it is clear that Russia does not have purely geographical interests there. It has partners such as Cuba, a real outpost to balance the overwhelming power of the thalassocrats. This was historically very important during the Cold War, a real ‘inside job’. The Gulf of Mexico is extremely distant and has no direct influence on Russian territory, but it is rather one of the faces of Anglo-American thalassocratic power and, moreover, a fundamental trade channel, with Panama and its surroundings still undergoing major changes. On the other hand, the US and the UK are the two thalassocratic powers par excellence and exploit that basin as a ‘safe haven’ between the two great oceans.

Therefore, in order to maintain its stability and confirm the realization of its continental vocation, Russia must keep at bay all the actors interacting in the three seas and ensure the strengthening of the Rimland, the security belt that separates it from the direct influence of the sea powers. And this seems to be exactly what Russia is doing.

In the eastern sea, its military presence is stable and it has excellent relations with all its neighbors. In the Mediterranean, it is easy to imagine that a situation of non-blackmailability and non-aggression is easier to manage than an internal conflict and, as we have seen in recent days, provocation in the Black Sea continues with the disputes over Crimea. With regard to the Caribbean, strengthening the network of partners and consolidating existing relations are the preferred way to prevent the US from gaining total control over the passage between the two oceans.

Russia from sea to sea, not only between its geographical borders, but above all between the seas of the world. Because only a tellurocracy that has fully realized its continental vocation can truly face the waves of the seas.