Let’s briefly retrace one of the fundamental steps in reaching the current status quo: the dissolution of the order that reigned in Europe.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

First rule, conquer

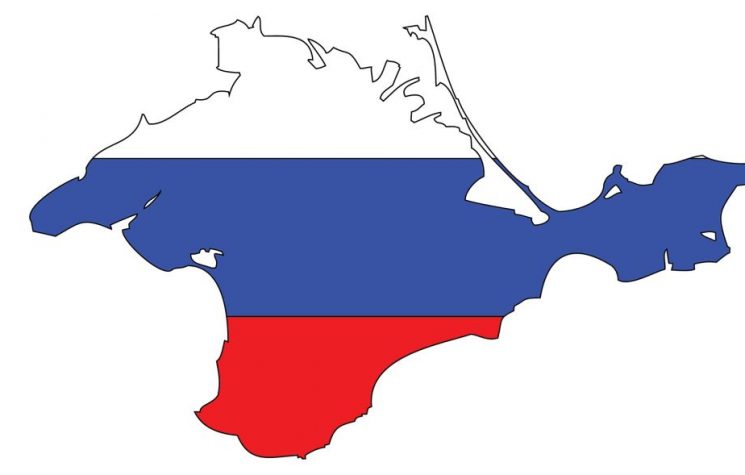

The choice to promote a global order dominated by the collective hegemony of the West after the Cold War had profound consequences for European security. It was clear that NATO enlargement would compromise efforts towards an inclusive pan-European security architecture, leading to a new division of the continent, the isolation of Russia and the reignition of latent conflicts. Many political leaders had warned of the risks of a new cold war resulting from the expansion of the Alliance; however, it was pursued by taking advantage of Russian weakness, with the conviction that any crises could be managed by the West. The expansion of NATO was conceived as a guarantee against future clashes with Russia, which, paradoxically, would have been triggered precisely by this expansion. This contradiction, which led the West into direct confrontation with Moscow, became a central element of the new world order.

There have been many attempts to build a pan-European security architecture based on the Westphalian principles of egalitarian sovereignty, indivisible security and a continent without divisions. The expansion of NATO, on the other hand, rejected this balance of power, favoring the inequality of sovereignty, strengthening its own security at the expense of Russia’s and perpetuating the fragmentation of Europe with a permanent military alliance in peacetime. NATO became an instrument for consolidating U.S. hegemony in Europe and for the strategic containment of Russia, hindering its capacity for nuclear retaliation. For Moscow, these developments represented an existential threat, pushing it to oppose Western unilateralism and to promote multilateral alternatives, although always based on the Westphalian principles.

A common European home against an integrated and free Europe

After the division of Europe after World War II, the capitalist and communist blocs tried to maintain a balance without compromising their respective regional orders. The Helsinki Accords of 1975 marked a turning point, establishing a common framework for European security and reinforcing fundamental principles such as equal sovereignty, indivisible security and respect for territorial integrity. At the same time, principles of justice were sanctioned, such as the self-determination of peoples and respect for human rights.

These developments favored Gorbachev’s internal reforms and his proposal for a “common European home”, which foresaw the demilitarization of foreign relations with the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact and NATO. The model envisioned by Gorbachev aimed to overcome the logic of blocs, replacing them with a single European institution to harmonize ideological differences. The United States, however, countered this vision with the concept of “a whole and free Europe” in 1989, also rejecting Mitterrand’s project for a European confederation. Fearing a possible unification of Europe outside of the Atlantic institutions, Washington insisted on the universalism of liberal democracy as the basis of the European order, aiming to extend the transatlantic system under its own leadership. The choice of names, decades later, sounds really curious. The Anglo-Americans never abandoned the communicative marketing strategy according to which the USA stood for freedom and Eastern Europe for slavery and oppression, even when this turned out to be exactly the opposite.

Despite many contrasts, the end of the Cold War led to progress in pan-European integration. The 1990 Charter of Paris for a New Europe, inspired by the Helsinki Accords, outlined a new security order, reaffirming the principles of equal sovereignty, indivisible security and a continent without barriers. In all this, a contradiction remained between the right of states to freely choose their own alliances and the principle of indivisible security. Although each state had the right to join NATO, the expansion of the Alliance would redivide the continent and undermine the concept of common security. And since NATO became the main guarantor of security in Europe, states had no choice but to join in order to guarantee their protection, since any independent alternative was opposed by Washington. Russian efforts to promote alternative integration, such as the proposed economic union between Russia, Belarus, Ukraine and Kazakhstan in 2004, were seen as attempts to restore Russian influence and were rejected by the West. Similar opposition occurred with security agreements between China and other nations, showing that the principle of “freedom of choice” was only supported when it favored the Atlantic order.

The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), created in 1994 to reinforce the Helsinki principles, remained marginal due to the U.S. reluctance to share leadership of European security. NATO thus confirmed itself as the main instrument of American domination on the continent. As Brzezinski observed, “Europe is America’s essential geopolitical bridgehead in Eurasia” and NATO served to root the U.S. political and military presence in the region.

Dividing Europe to consolidate U.S. hegemony

The expansion of NATO led to a new division of Europe and renewed hostility with Russia. In 1994, U.S. President Clinton recognized that an enlargement of the Alliance could recreate divisions, and initially proposed a Partnership for Peace as an alternative. However, this initiative quickly became a springboard for NATO membership, making Washington’s intention to progressively integrate the former Warsaw Pact states into the Alliance clear.

Despite Western reassurances, Russia interpreted these moves as a threat to its security. Already in 1994, Boris Yeltsin warned Clinton that NATO was creating “a new rift in Europe”. Many American diplomats, such as Ambassador Pickering, recognized Russia’s extreme sensitivity towards the Alliance’s expansion. However, the belief that Moscow was too weak to react prevailed in Washington. Defense Secretary William Perry admitted that the United States had ignored Russian concerns, treating it as a “third-rate power”.

Many foreign policy experts opposed NATO expansion, fearing it would isolate Russia and make true collective security impossible. In 1997, fifty American analysts wrote to Clinton calling the enlargement of the Alliance “a historic mistake”. The U.S. strategy was based on the idea that a weakened Russia would have to accept the new balance of power. This presumption proved to be wrong, leading to a deterioration of relations and the emergence of a new phase of geopolitical confrontation.

A strategy of neo-containment

A totally different containment strategy was needed. John Matlock – U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union from 1987 to 1991 and one of the key players in the negotiations that ended the Cold War – emphasized that public opinion had been led to believe that NATO aimed to eliminate divisions in Europe, when in reality these had already disappeared. In his opinion, “the expansion of the military alliance, which had maintained a defensive line in the heart of the continent, was a sure way to rekindle the divisions”. Instead of honoring the commitment to build an inclusive European security architecture, Matlock said that Washington had repeated the mistake of the 1919 Treaty of Versailles, excluding Russia and imposing a security system that perpetuated its fragility.

Despite the official rhetoric about extending peace and stability, NATO was simultaneously preparing for a possible confrontation with Russia. Supporters of Clinton’s decision to expand the military alliance justified the initiative by calling it an “insurance policy” against possible future tensions with Moscow. What Yeltsin perceived was that his interlocutors in Washington were preparing an insurance policy to guarantee themselves an advantage over Russia in the event that relations deteriorated. As early as January 1994, before NATO’s expansion had been decided, Secretary of State Warren Christopher and Clinton’s adviser on Russia, Strobe Talbott, argued that the enlargement of the alliance would make it easier to contain Moscow. Thus, after the Cold War, NATO justified its existence by addressing the security threats that its own expansion helped to generate. Former Secretary of State James Baker warned that this strategy risked becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy: those who supported the enlargement of the alliance wanted to be prepared in case Russia responded by expanding itself, but this same expansion could have pushed it to do so. Criticizing the return to a policy of containment, Baker emphasized a fundamental point: “The best way to make an enemy is to look for one, and I fear that is what we are doing in trying to isolate Russia.”

To avoid provoking a hostile reaction from Moscow or appearing too aggressive, in 1994 the expansionists within the National Security Council argued that NATO’s cohesion depended on strategic ambiguity towards Russia. While some Western European states were unwilling to openly declare Moscow a threat, some Eastern European countries would have lost confidence in the alliance if it was not perceived as a bulwark against Russia. Although the Eastern European countries had historical reasons to fear Moscow, the use of NATO as a containment tool aggravated the security dilemma, increasing Russian insecurity. The relationship between NATO and Russia has therefore developed around the contradictory “deterrence-cooperation dichotomy”: on the one hand, the alliance tried to contain Moscow, on the other hand it tried to reassure it by denying that it considered it a danger, to avoid negative reactions.

The USA has an interest in maintaining a level of tension with Russia, in order to feed the idea of an external threat, strengthening the cohesion of the alliance and limiting economic integration with Moscow. American influence in Europe depends strongly on the region’s dependence on the security guaranteed by Washington: an excess of trust and stability would reduce this control. Furthermore, the military-industrial complex has played a key role in promoting NATO expansion, seeing it as an opportunity to increase profits. They invented think tanks as a tool to replenish the territory and get rid of some of the work that needs to be done to proceed with the expansion.

Towards a new cold war

Many American leaders were aware that conflict, and even war, could be probable consequences of NATO expansion.

In 1997, during a Senate hearing, Ambassador Matlock warned that NATO enlargement could be “the greatest strategic mistake since the end of the Cold War”. He explained that this policy “could trigger a series of events capable of generating the most serious threat to American security since the collapse of the Soviet Union”. In equally strong terms, Pat Buchanan, former advisor to Nixon, attributed to Washington the responsibility for the increase in resentment in Russia: “It is the fault of the American elite, who have done everything to humiliate Moscow. Why are we doing this? Buchanan predicted that Russia would eventually respond to this threat, forcing the United States to choose between a confrontation with a nuclear power determined to re-establish its sphere of influence or a withdrawal from its NATO commitments.

The expansion of NATO profoundly altered the European military balance, contributing to the progressive dismantling of arms control treaties. The deterioration of the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE), accentuated by the NATO missile shield, was a clear sign of this. Even fundamental treaties such as the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty, the INF Treaty and the Open Skies Treaty collapsed, marking the decline of a security architecture based on cooperation and reciprocal obligations.

Since the beginning of the 2000s, NATO has continued to expand at a rapid pace, in step with the Russian Federation’s economic and commercial acceleration, reaffirming our status as a global power. The Americans – and the British – knew how to do it and when to do it.

Destabilizing and dissolving the pan-European order was fundamental to opening the way for the next step: bringing the war to Europe. And so we come to the present day.