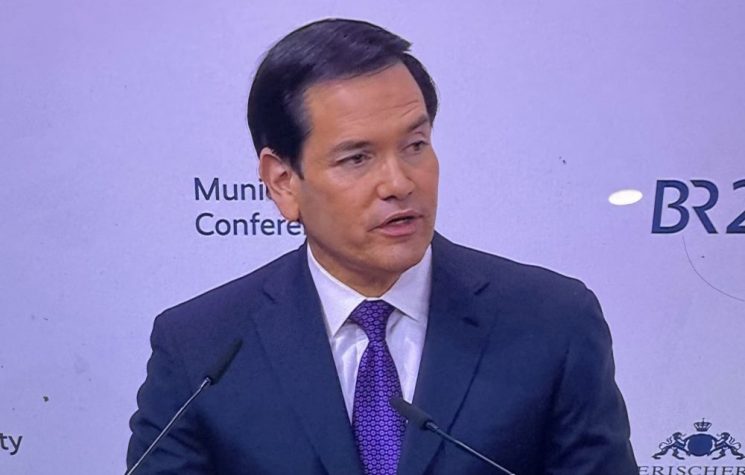

With less than a month until the next big NATO meeting, scheduled for the first week of December, France’s Macron has jumped into public relations mode to prepare the public for some big changes on the horizon. Indeed, Macron’s major interview with the Economist on November 7th on the question of the US’s alleged wavering commitment to NATO is a stunning sign of the times.

Europe wants its own Army

Cutting through a lot of intentionally confusing messaging, is that France and Germany are just fine with any end to NATO because it helps justify the coming European Army – one that they want, and believe they need anyhow. It only happens to be part of the same reality that US hegemony, and its ability to finance NATO in turn, are coming to an end. In sounding more like a radical post-structuralist international relations theorist than a fiscally conservative leader of a capitalist democracy, Macron shocked the world when he stated in no uncertain terms that this period we are in marks the end of ‘Western Hegemony’.

The real facts of motives behind big changes have an odd way of ultimately making themselves known for what they are at the end of the day. Often these are cloaked in the underlying framework of the politics of the time. Revealing these in the case of France and NATO can show some top-level word salad at play: justify independence not on the basis that being controlled isn’t fair, but rather that those doing the controlling aren’t doing it well enough and don’t seem committed to it as much as they ought to be. Macron is doing this very well, and mirrors Trump’s own discursive games.

Occupiers aren’t doing their job – the End of Trilateralism

Imagine if you will a French argument against the Nazi occupation not because it placed Germany in control of France’s fate, but rather on the basis that the Wehrmacht was decreasing its troop presence in France, or conversely appeared to be wavering on the Eastern Front, and as a consequence France was worried about Germany’s commitment to the Reich. This is, in short, what Macron is arguing today regarding the US and NATO.

Imagine likewise, that the Wehrmacht said it was considering abandoning its occupation of France not because it had to move resources to the Eastern Front, but because France wasn’t giving enough to the war effort. This is the crux of Trump’s argument for public consumption.

Under any other prior historical iterations, the US’s moves to reduce its NATO commitments to Western Europe would be hailed by progressives in the Democratic Party in the US as a step in the right direction. Yet now in this exciting time, one in which the US Empire is down-sizing and adjusting itself to its real force potential, progressives in the US are making geopolitical realism into a partisan issue: since the most obvious or observable stage is happening under a nominally conservative, Republican administration, it must therefore be a Democratic Party talking point to oppose this in principle.

The matter is of course deeper than this, and the Democratic Party’s investment in the trilateralism (US + EU + Japan) of Rockefeller and Brzezinski has been at odds with the unilateralism of the neoconservatives. We will recall when President George W Bush attacked Iraq, it came not long after moves by the Iraqi government to do their oil dealings in Euros. The Europe-wide hatred for Bush’s war on Iraq seemed to the politically naïve as an expression of social-democratic pacifism, but in reality was an expression of Europe’s sovereign financial interests versus dollar hegemony. These questions really have not gone away.

When NATO came onto the stage, it was couched in terms of protecting Western Europe from the growth of the Soviet sphere of influence which the latter had won from its victory over Germany in WWII.

The idea that NATO was not a collaborative and mutual effort of freely-acting European states in defense of market freedoms and Western values, but instead more like a US led and sustained military occupation in Western Europe, in the past could be criticized as either Communist or even neo-Nazi propaganda. Against this view the entire media-academic industry was mobilized, assuring the public that all the European countries of NATO were members of their own accord and will: an outgrowth of the democratic mandate from the peoples of the member states, arrived at through fair parliamentary processes.

Macron still needs to make everyone look good

All this places Macron in an odd position. NATO is the military component of economic Atlanticism, but this transatlantic relationship experienced a major breach of trust in the years following the US market crash in 2007. This was because US based banks and government colluded to deceitfully push a significant portion of its liabilities onto the EU all the while claiming these were investments – who in turn placed an undue burden in PIIGS countries, in particular Greece. This all in turn has fueled a marked increase in Eurosceptic and ‘exit’ movements across the beleaguered EU.

Then on top of that, the Trump administration makes the EU’s commitment to NATO a cornerstone of his Europe policy, along with a brewing trade war. These two are intimately connected.

And so Macron’s apparent lamentations over the ‘brain death’ of NATO is quite revealing. In this, he refers to truths that everyone knew, but couldn’t say: “NATO is essentially a military occupying force against European sovereignty – for the EU to be a geostrategic entity, it must be in control of its own military forces”. This sounds like it could have been said by de Gaulle, even Pétain, and while the notion easily fits with Marine Le Pen’s platform, the reality of France forces Macron to hold it.

Europe’s not in love with Atlanticism

The problem is that even though transatlantic financial dealings have increasingly less to offer the EU, the US side of this equation needs to maintain the relationship and all the appearances and structures that go along with it, in order to leverage itself in any future potential dealings. In short, one way that the US believes it can hold onto things longer, or decrease the tempo at which they’re losing them, is by keeping up appearances. And these appearances are more than just superficial – they are real existing financial obligations which in all reality do not work well for European institutions.

Macron has iterated the call for an EU army a number of times. But his statements in the economist represent a skillful if distorted way to couch the EU’s real situation within the accepted discourse of our time: Atlanticism is good. This mirrors Trump’s method and reasoning – and to be clear, it is not certain that Trump is very much committed to trans-Atlanticism, at least not in its present iteration.

Back in August, speaking on how isolating Russia is a mistake, Macron explained that “Western hegemony” is over. This leave us an interesting formula: Western hegemony is over, European regional hegemony must begin. This implies that Western hegemony had always meant Europe plus the US together. Without the US, there is no Western hegemony.

Trump’s calls that EU countries increase its funding of NATO on the rationale that Europe isn’t doing their share, could only have been to provoke a reaction from Europe to speak its own truth – ‘we don’t like NATO either’ – and to justify the US’s own eventual reorganization or dismantling of NATO. Like Imperial Japan told its puppet-state Manchukuo: it’s only natural that you should pay for the cost of your own occupation.

If NATO member states no longer want to pay for their own occupation, then they will no longer get to enjoy it.

Macron masters Trump’s Discursive Trap

Macron, likewise, plays a similar game – and his discourse is aimed at being acceptable to multiple audiences, who themselves have greatly divergent interests and positions.

The realists in the US, of which Trump is the most evident representative, know that the US simply cannot afford to continue with its NATO obligations. Underneath this is the fact that the US cannot offer Europe better deals than it can get elsewhere. The days of forcing Europe to work through the US through various ways, wherein using the US dollar as the primary transaction currency and the global reserve currency in the past meant that the US was middle-in to every deal. Those days are just about over. Rather than disclose that all this is about decreasing US influence, power, and wealth on the global scene, it is more prudent to make this about fairness – that the EU isn’t doing its part.

And to wit, as we have said, for Macron’s part of the dance – he knows he needs to keep the trans-Atlanticists happy, they still exert tremendous political control in Brussels and are interwoven into Europe’s financial sector – the most important sector in capitalist Europe. There can be no doubt: Macron was the banking establishment’s choice against Le Pen. The question as to whether he was some Manchurian candidate from beyond the financial sector’s grasp, or whether there is some pro-European sovereigntist faction within the European side of this transatlantic financial sector, is a fascinating question for later investigation. But sufficed to say, those transatlantic deals aren’t the best deals, but these institutions are using whatever influence and capital they still have to force a political position. Macron, nominally, wants to keep them happy.

Thus Macron’s ‘warnings’ and ‘lamentations’ that the US under Trump has abandoned its NATO commitments in controlling Europe’s military are anything but. These ‘lamentations’ will serve a perfect pretext for France and Germany to work together to organize a Europe-wide military force. In reality, this has been brewing for many years under the rubric of NATO command. In essence, all the structures are there, it is only necessary to remove US command from the structure and change some patches and flags.

In speaking to the Economist regarding NATO’s Article V provision (in which NATO members must rally on the side of a NATO state if it is attacks and invokes the article), Macron seems to imply, in some twisted and round-about – really convoluted way – that he questions the US’s commitment to NATO because of the way it abandoned its allies, the Kurds. This is doubly odd – the adventure in Syria was not a NATO operation, and it is Turkey, the force attacking Kurdish separatists in Syria, that is the NATO ally. Turkey is NATO’s second largest army after the US.

Macron isn’t wrong then to imply – what is NATO without the US and Turkey? It is the European Army. This is the view which both France and Germany enter into the December meeting with.

So while Trump hides that the US simply can’t afford its empire anymore by blaming Europe for not doing its share, Macron hides that Europe’s been pushing for its own army for years before Trump assumed office. Indeed, the EU’s CSDP, known also as the European Defense Union, has been around in in developing form since 1999, the same year the currency was launched. This has been a part of the plan, it would seem, for quite some time.

Macron and Trump can’t be faulted for the word salad they are serving: it’s only a reflection of what’s acceptable in our day. The US president and European leadership appear to agree that NATO’s days are over. It seems the transatlantic financial institutions are the primary team expressing deep concern of this, and are looking to slow the process down by reversing the most overt policies of Trump by ousting him from the White House in 2020. Doing so could drag the process out for another decade, but doing so would be more painful and costly for everyone in avoiding the inevitable.