It was October 1917. Not quite sixty years since the first Populists, or narodniki, began to build a revolutionary movement in Russia to overthrow the tsarist autocracy. Sixty years is a long time for a revolutionary movement to sustain itself and grow stronger. Through three generations, succeeding ranks of revolutionaries took up the cause in spite of defeats and setbacks and in spite of tsarist police repression. Finally, in February or March 1917 according to the Julian or Gregorian calendars, the tsarist autocracy collapsed. This deus ex machina came about unexpectedly, a gift from the Gods for the revolutionary movement, but a koshmar for the privileged tsarist elite. The last of the Romanovs, Tsar Nicholas II, was forced to abdicate. He was a victim in some ways of his own doing. He had led Russia into the Great War in August 1914. Large territories had been lost, millions of soldiers were casualties, and the Russian economy was collapsing. The elite of tsarist society had to pull in their belts as economic conditions worsened, but the menu peuple, the masses of workers and peasants, endured far greater hardships. Workers could not feed their families or keep them warm during the winter; and peasants were the chief source of cannon fodder to feed a war in which they had no tangible interests and produced only tragic news about fathers and sons who would never return home.

Thus it was that women demonstrating for bread in the streets of Petrograd, the Russian capital, set off the popular movement which brought down the tsar. The army went over to the people and the seemingly eternal, all-powerful tsarist order fell apart as though it were only a child’s house of cards. New democratic organs of government were set up; they were called Soviets (or councils) of workers’ and soldiers’ deputies and they spread rapidly across the country.

Women demonstrating for bread in the streets of Petrograd, the Russian capital, set off the popular movement which brought down the tsar

Some historians claim that the tsar’s abdication was a fluke and that the Russian people were passive participants in the revolution of 1917, oafish clods in effect, who did not know their own interests and were easily fooled by a tiny party of murderous Bolsheviks. These historians pursue a “neoliberal” political agenda to discredit the revolution of 1917 and the men and women who led it. They are Atlanticists and Russophobes settling old scores with past generations of historians or projecting Bolshevism on to the present leadership of the Russian Federation and in particular on to its president, Vladimir Putin, as absurd as that may seem. History is politics when it comes to the USSR and Russian Federation.

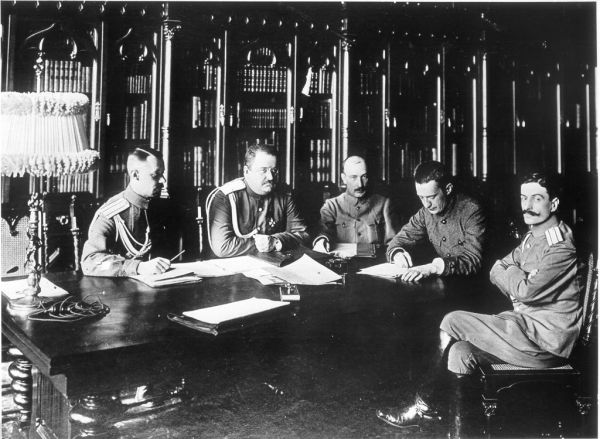

Alexander F. Kerensky, the leader of the new Russian government, was no more a socialist, or a democrat for that matter, than an actor playing that role on stage

In fact, the abdication of the tsar was no fluke, and the common people were not passive, dull-minded or easily manipulated. Workers, soldiers and peasants had nevertheless to learn to distinguish between the various “socialist” parties who wanted to lead them. These were in the main Socialist Revolutionaries (SRs), Mensheviks and Bolsheviks. The first two groups claimed they could not lead the revolution without the help of “the bourgeoisie”, in particular, the K-D or Kadet party, representing the former urban and rural tsarist elites. But Kadets did not want to secure the revolution; they wanted to stifle it before it could harm their economic and financial interests. The SRs and Mensheviks, timid socialists, could talk a long streak, but then hesitated before the precipice of revolutionary action. They therefore ceded power to the “more politically experienced” Kadets and other members of the tsarist elite, organised into the so-called Provisional Government. This was ironic, since the ministers of the Provisional Government were neither democratically elected nor revolutionaries.

The leader of the new Russian government came to be Alexander F. Kerensky, a so-called Trudovik, or a member of an S-R breakaway faction. Kerensky was no more a socialist, or a democrat for that matter, than an actor playing that role on stage. He saw himself as a potential dictator and boasted of it. On the key issues, he wanted to keep the war going and to stall land reform. These questions were the only things that mattered to peasant-soldiers who thought solely of staying alive and returning to home to profit from land redistribution. Kerensky was as determined as his Kadet colleagues to stop the revolution, close down the Soviets and jail or hang the Bolsheviks.

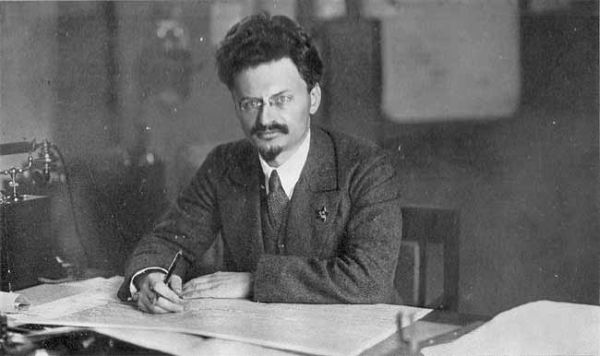

L. D. Trotsky was one of the most important and visible leaders of the Bolshevik party

Yes, the Bolsheviks were Kerensky’s bête noire. They were real revolutionaries who would not be satisfied with seeing off the tsar and then collaborating with the tsarist elite. The SRs and Mensheviks, who in March held a majority in the Petrograd Soviet, quickly lost ground to the Bolsheviks. The revolutionary movement galloped to the left, and Kerensky could not stop it. Soldiers and workers, who at first did not recognise the differences between various “socialist” politicians, became more sophisticated in the ensuing months. They were smart enough to know their interests, essentially peace, land and bread, and to understand that the only party willing to take up these political objectives were the Bolsheviks. If they were a minority party in March; by autumn the Bolsheviks held majority positions in many Soviets, the most important being Petrograd and Moscow. For the SRs and Mensheviks, it was galling to see their popular base erode away.

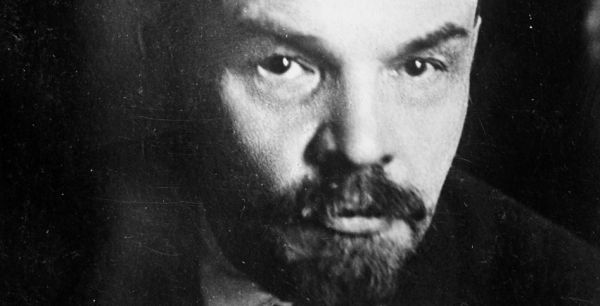

Lenin pushed his idea to govern through control of the Soviets on 10/23 October, and plans were set in motion to overthrow the Provisional Government

V. I. Lenin and L. D. Trotsky were then the most important and visible leaders of the Bolshevik party. Trotsky became president of the Petrograd Soviet in the early autumn, while Lenin formulated policy and pushed it forward amongst his highly independent-minded colleagues. Overthrow the government of landlords and capitalists, he said. “All power to the Soviets” became Lenin’s watchwords. The Bolsheviks would govern through control of the Soviets. This idea was easier said than done because many Bolsheviks were uncertain whether they had sufficient popular support to take and hold power. Petrograd was red, but what about the rest of the country? Lenin pushed his idea through the Bolshevik Central Committee on 10/23 October, and plans were set in motion to overthrow the Provisional Government. A week later, a Military Revolutionary Committee (voenno-revoliutsionnyi komitet) was set up. It was dominated by Bolsheviks but was an organ of the Petrograd Soviet and included Left SRs and anarchists amongst others. Its task was to take the concrete measures necessary to transfer state power to the Soviets. This meant in the first instance asserting control over garrison troops and weapons depots heretofore under the nominal authority of the Provisional Government. Sailors from Kronstadt and Helsinki were ordered to move to the capital. Some Bolsheviks, like L. B. Kamenev, opposed an immediate seizure of power. Lenin was beside himself with fury.

“Hurry,” he responded when preparations seemed to be lagging. “Not enough,” he would scowl when it seemed too few sailors and soldiers were ordered to the capital. The overthrow of the Provisional Government had to be accomplished before the opening of the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets on 25 October/7 November. “The government is tottering,” Lenin told his colleagues: “It must be given the deathblow at all costs. To delay action is fatal.”

On Sunday, 22 October/4 November, the best Bolshevik orators went out into the city to rally support. Trotsky’s speech that day at the House of the People drew a huge crowd. “The revolution is in danger,” Trotsky declared: “Only you can defend it.”

“Will you support the Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies?” he asked.

As one, his listeners raised their hands. “We swear it,” they shouted.

“Let this vote of yours be your vow,” Trotsky responded, “with all your strength and at any sacrifice to support the Soviet….”

Still holding up their hands, the crowd responded again, “We will, we swear it.”

Wherever Trotsky spoke to rally workers and garrison soldiers, he was greeted with commotion, excitement and thunderous hurrahs. When he rose to speak, the bustling crowd would finally settle down to listen. “It became still,” one observer remembered: “there followed not so much a speech as an inspirational song.” Who can say the workers and soldiers of Petrograd were passive by-standers, stupid oafs, who could not understand their own interests?

“In the relations of a weak government and a rebellious people there comes a time when every act of the authorities exasperates the masses,” wrote American journalist John Reed

In the meantime, Kerensky could feel the noose tightening around the neck of the Provisional Government. He was meeting his cabinet daily to take measures to stop the Bolsheviks. Indictments were issued against the members of the Military Revolutionary Committee. Unfriendly newspapers were ordered shuttered; editors and journalists were to be arrested. Young military cadets, convalescing war-wounded, a shock battalion of women, anyone who could walk or limp with one leg or two was ordered to a duty station. Kerensky was trying to get the cold, iron grip of the Military Revolutionary Committee from around his neck.

On orders of the Military Revolutionary Committee, soldiers, sailors and Red Guards set up checkpoints around the capital

To no avail. Orders went unanswered. Newspapers which had been closed were reopened on Trotsky’s orders. The more Kerensky tried to loosen the noose around his neck, the more it tightened. “In the relations of a weak government and a rebellious people there comes a time,” wrote American journalist John Reed, “when every act of the authorities exasperates the masses….” That time had come. Kerensky, said one Left SR, could not find a dozen soldiers who would come to his defence.

On orders of the Military Revolutionary Committee, soldiers, sailors and Red Guards set up checkpoints around the capital. Government troops guarding the bridges across the Neva were dispersed and replaced by detachments loyal to the Petrograd Soviet. Key offices were occupied—post, telephone and telegraph, the state bank, railway stations and junctions. The noose was tightening still more around Kerensky’s neck, and few people seemed to care. Typically, some woe-begotten Mensheviks tried to save his skin and that of the Provisional Government. It was too late.

Scenes around the capital were surreal. While some parts of the city were dark and shuttered, the fashionable Nevsky prospekt was open for business as usual. Prostitutes were out and about, looking for clients. Gambling saloons were open, noisy and stinking of tobacco smoke and cold sweat. For lounge lizards and the wealthy elite it was perhaps a last chance to swig champagne and challenge Lady Luck. Smartly dressed couples walked arm in arm, perhaps planning to go to the theatre or to a restaurant where no workers or soldiers ever ventured except as janitors and dishwashers. The trams were running, noted John Reed, and the shops and cinemas were brightly lit. “We had tickets to the Ballet at the Mariinsky Theatre—all the theatres were open,” he remembered, “but it was too exciting out of doors.”

At around 9:30 pm the cruiser Aurora, anchored in the Neva, fired a reverberating blank round, which encouraged other defenders of the Winter Palace to abandon their posts

In the meantime, Lenin huffed and fumed whenever he perceived the slightest slackening of action. The Military Revolutionary Committee became more aggressive. In the early hours of 25 October/7 November insurgent soldiers took control of the Petrograd electric station. Electricity to most government buildings was shut off. So were telephone lines to the war ministry and to what became the last redoubt of the Provisional Government, the Winter Palace. At 11am that day, Kerensky left Petrograd in a borrowed Renault from the US embassy to look for loyal troops. His search was all but fruitless. “We can say,” the head of the French Military Mission reported to Paris, “that he [Kerensky] no longer has a single supporter.” At about the same time the Military Revolutionary Committee issued a proclamation sent across the country declaring that the Provisional Government had been overthrown.

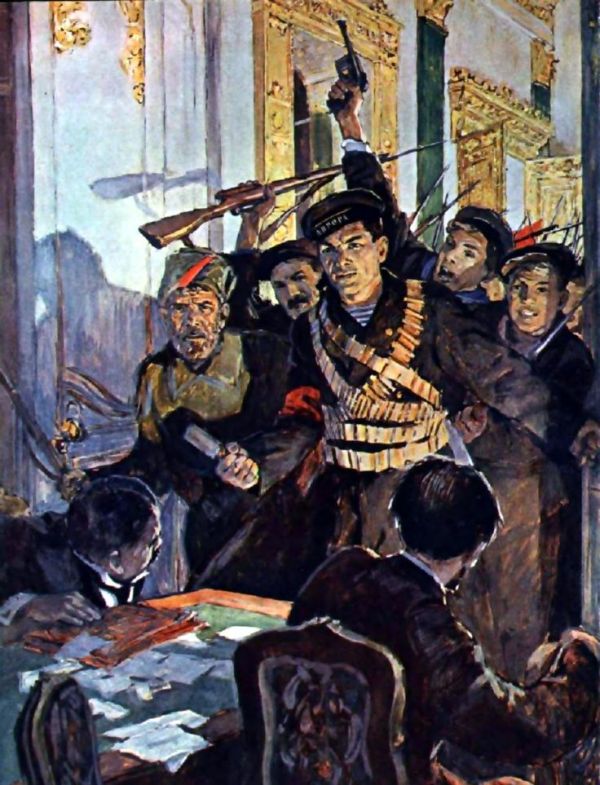

At about 2 am on 26 October/8 November, forces of the Military Revolutionary Committee entered the Winter Palace

This was not quite true because the Winter Palace, where Kerensky’s cabinet was holding out, had not yet fallen. The building was sealed off, but there were hitches in logistics and delays in launching the final assault. Representatives of the Military Revolutionary Committee went into the palace to talk its defenders into leaving the building peacefully. Many did so. At around 9:30 pm the cruiser Aurora, anchored in the Neva, fired a reverberating blank round, which encouraged other defenders to abandon their posts. A little later artillery from the near-by Peter and Paul Fortress opened up, firing live rounds this time. Finally, at about 2 am on 26 October/8 November, soldiers and sailors entered the Winter Palace: cabinet ministers were arrested, their last defenders having given up without a fight. “Where is Kerensky?” soldiers wanted to know. They were furious that he had escaped their grasp.

There were still spasms of resistance in Petrograd. The first session of the All-Russian Congress of Soviets opened in the early evening of 25 October/7 November. There were pressures to create a so-called “joint all-Socialist government”. Lenin was having nothing of it for he had seen enough of Menshevik and SR “compromises” with the old tsarist elite. Even then, Kamenev was still trying to put a spoke in Lenin’s wheel. “We can’t hold on,” he whined, “Too much is against us. We haven’t got the men.” You can imagine Lenin’s furious reaction.

“We must now devote ourselves,” Lenin said, “to the construction of a proletarian socialist state.”

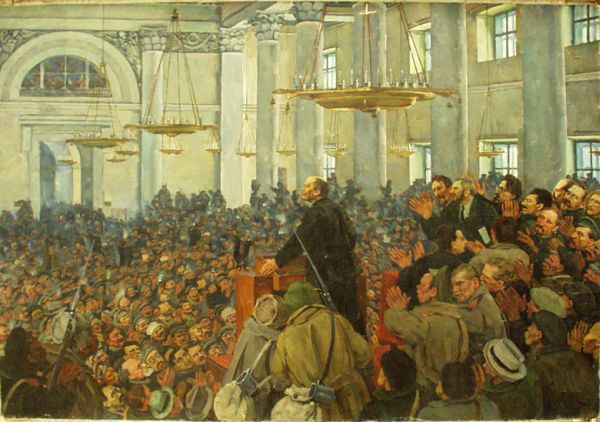

John Reed managed to get into the meeting hall and witnessed these events. Lenin arrived at the congress a little before 9pm. “A strange popular leader,” Reed wrote in his iconic Ten Days That Shook the World: “a leader purely by virtue of intellect; colourless, humourless, uncompromising and detached, without picturesque idiosyncrasies—but with the power of explaining profound ideas in simple terms… And combined with shrewdness, the greatest intellectual audacity.” As Lenin entered the congress hall, he and his comrades were greeted with “thundering waves of cheers”. “Bozhe ty moi [Oh my God], we’ve done it,” those delegates must have thought to themselves amidst the tumult. “We shall have a soviet government,” Lenin declared, “our own organ of power without the participation of any bourgeois….” That was the main point. “We must now devote ourselves,” Lenin concluded, “to the construction of a proletarian socialist state.” You can imagine the thunderous applause that followed his words.

“Lenin, with Trotsky beside him, stood as firm as a rock,” Reed remembered: “Let the compromisers accept our programme and they can come in! We won’t give way an inch. If there are comrades here who haven’t the courage and will to dare what we dare, let them leave…” The Left SRs stayed in. Mensheviks and an SR rump, walked out of the congress in the early morning hours to protest the Bolshevik seizure of power. They played right into Lenin’s hands.

Trotsky famously rose to respond to their departure. “A rising of the masses of the people requires no justification. What has happened is an insurrection, and not a conspiracy. We hardened the revolutionary energy of the Petrograd workers and soldiers… And now we are told: Renounce your victory, make concessions, compromise. With whom? I ask… With those wretched groups who have left us…? You are miserable bankrupts, your role is played out, go where you ought to go; into the dustbin of history!” The congress broke into tumultuous applause, and the last of the Mensheviks left the hall amidst whistling and mockery.

In Pskov, Kerensky met with General P. N. Krasnov, a Don Cossack general and no defender of the revolution.

Elsewhere, the mayor of Petrograd and deputies of the city Duma, still under the control of Kadets and SRs, demonstrated against the seizure of power. They spearheaded a “Committee for the Salvation of the Country” which planned an uprising to overthrow the new Soviet authorities and to restore the Provisional Government to power. Their idea was to act in conjunction with Cossack forces, which Kerensky was then seeking to lead against the Bolsheviks. The Military Revolutionary Committee having got wind of it, the insurrection launched prematurely and failed. Soldiers and workers in Petrograd were not going to risk life and limb to re-establish the rotten Provisional Government. Menshevik and SR willingness to ally with Cossacks raised by Kerensky marked their utter bankruptcy, as Trotsky would no doubt have noted with his characteristic disdain.

In the meantime, Kerensky had made his way to Pskov, the northern front army headquarters, about 280 kilometres southwest of Petrograd. He met with General P. N. Krasnov, a Don Cossack general and no defender of the revolution. On paper, Krasnov commanded large forces but he could only muster a thousand men to march on Petrograd. These were the same forces on which the Mensheviks and SRs counted to restore the Provisional Government.

“Kerensky counts on arriving in Petrograd tomorrow,” said one French report. That was on 28 October/10 November. Another report said Kerensky would arrive two days later. Almost the entire front was said to support “action against bolshevikism (sic).” That must have been a moment of French wishful thinking. On that day, in fact, Krasnov’s small force was defeated and dispersed at Pulkovo, not far from Petrograd. It was a bloody fight with serious losses on both sides. Soviet commanders paroled Krasnov and his surviving men in exchange for a promise not to take up arms again against the new Soviet government. It did not pay to be so generous for Krasnov had no intention of respecting his parole and went south to organise an anti-Bolshevik army. As for Kerensky, one French telegram to Paris indicated that after talking of suicide, he had “disappeared”. In fact, he went into hiding before fleeing the country and eventually ending up in Paris. Such was the ignominious end of the would-be all-powerful dictator of Russia.

There was also some fighting in Moscow, but there, too, Soviet forces took the upper hand. Soviet authority spread quickly across the country, although not everywhere. In the Ukraine, the Cossack territories and the Caucasus opposition sprang up, encouraged by Entente agents carrying bags of rubles. Lenin’s attention was bracketed on internal enemies so that he apparently failed to anticipate the danger, which might come from Russia’s western allies, intent on overthrowing Soviet authority. The spread of world revolution, he gambled, would take care of German imperialism, but what about the Entente? And what if Soviet peace proposals went unanswered? “We want a just peace,” Lenin explained, “but we are not afraid of a revolutionary war.” On s’engage, et puis on voit. Lenin knew this axiom from Napoléon and even cited it years later to explain how the revolution had been victorious. That was hindsight. In the meantime the Allied governments began to lay plans to destroy the nascent Soviet republic. What then would the Bolsheviks do?