The West does not get the full truth about lives and aspirations of the Crimean Tatars, a Turkic ethnic group traditionally living in Crimea. There are a lot of myths on their history and destiny, created by interested foreign parties. The author will try to show the facts to help the readers make their own conclusions.

First we have to introduce our readers Mustafa Dzhemilev and Refat Chubarov, chiefs of the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar, who actively produce fake news about Crimean Tatars. Dzhemilev and Chubarov have a long lasting friendship with Turkey. Why Turkey?

Turkey has always regarded the Crimean Peninsula as its sphere of interests. Ankara sought to fuel separatist sentiments among Crimean Tatars via the Mejlis’ youth, educational, cultural and religious programmes and joint business. Turkish politicians dreamed about the Crimean Peninsula once again under the direct influence of the new Ottoman Empire.

The Obama administration-inspired coup d’etat in Ukraine in 2014 dramatically undermined Turkey’s plan for Crimea. Back in 1997, the US declared the Black and Caspian Sea region to be one of its areas of vital interest and began hatching plans for the peninsula: to establish a military base in Crimea that would open up huge possibilities for US control over the Black and Azov Seas, the Bosphorus and Dardanelles straits, the Caucasus, and Turkey.

Ukraine, meanwhile, needed the Crimean Tatar community as an ‘argument’ for the annexation of Crimea between 1991 and 1995, when the peninsula became part of Ukraine against the will of its residents and Crimea’s statehood was abolished with the help of military force. The Crimean Tatars regarded Kiev as a counterbalance to the Russians, who make up a clear majority of the population in Crimea.

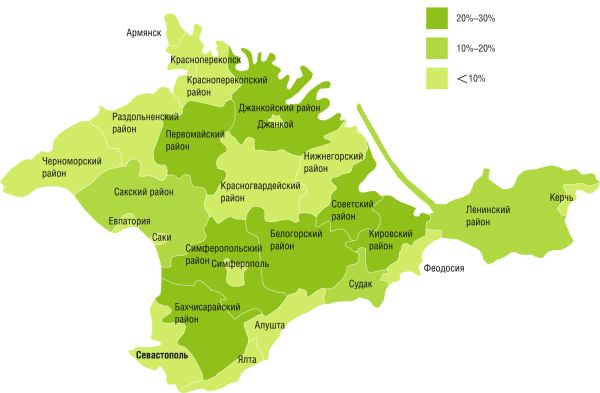

Percentage of Tatar population in Crimea (2014)

In the first half of the 1990s, the Ukrainian authorities encouraged the resettlement of Crimean Tatars in the peninsula and by 1995 their numbers had increased to around 10% of the population (1.58% in 1989). At the same time, Kiev tried to nip the Turkey’s influence on the Crimean Tatars and so, in 1998, Kiev made the process for obtaining citizenship more difficult for Crimean Tatars and abolished the quota for their representation in the Supreme Council of Crimea (14 seats). In response, the Mejlis’ activists blocked the motorways and railway to Simferopol on the eve of the parliamentary elections and demanded 25 seats in the Crimean Parliament instead of 14. Skirmishes began with the police and Kiev sent tanks into Crimea. In the elections, the Mejlis did not get a single one of the 100 seats in Crimea’s legislative body.

Really, since the moment the Mejlis was founded in Crimea, it has been geared towards the organisation of large-scale riots. In 1992, the Supreme Court of Crimea recognised the organisation’s activities as unconstitutional – following a riot by Mejlis members on 5-6 October in Simferopol. This kind of behaviour suited Kiev at the time, however – they even turned a blind eye when the Mejlis began organising armed units. But this is what’s interesting: Ukraine did not officially recognise the Mejlis as representing the interests of Crimean Tatars right up until… Crimea joined Russia. Which is why it is now so surprising to hear Ukraine making demands on Russia with regard to the Mejlis, a body that Ukraine refused to recognise for 23 years and against which it used military force in 1998.

During the Euromaidan in Kiev the Mejlis leaders Mustafa Dzhemilev and Refat Chubarov attempted to turn the vacuum of power in Ukraine to their advantage by organising large-scale separatist riots in Crimean capital Simferopol. For Crimea, where Tatars are 12% of the population, the plan was completely insane. Yet from January 2014, the Mejlis began heating up its own ‘Crimean Maidan’: there were renewed calls for quotas in parliament and organised rallies for early elections. But the popular support of the Mejlis’ leaders is quite limited since the long terms of presence of Mustafa Dzhemilev and Refat Chubarov in Verkhonva Rada of Ukraine didn’t bring any tangible profit for Crimean Tatars. Even the most important issue – the status of the Crimean Tatar language – was never seriously considered by Ukrainian legislators while Crimea belonged to Ukraine.

Leader of the pro-Russian interim administration in Crimea Sergey Aksenov trying to calm down the emotions during the Crimean Tatar rally in Simferopol, February 2014

In the run-up to the Crimean status referendum held in March 2014, the Mejlis leaders were spreading rumours among the Crimean Tatars that they would be threatened with deportation if Crimea became part of Russia. These turned out to be a lie, however, as did the predictions regarding the mass relocation of Crimean Tatars to Ukraine.

«Many of those who left the peninsula have something to fear – e.g. they were members of Hizb ut Tahrir, a radical organization seeking establishment of a global Caliphate. This organisation, together with the Mejlis and Ukrainian ultra-nationalist Right Sector, have been preparing a large-scale bloody conflict in Crimea between the Russians and the Crimean Tatars», says Vasvi Abduraimov, a public figure in Crimea who represents the Milli Firka (the People’s Party). The Mejlis failed to present the world with a picture of the ‘mass exodus’ of Crimean Tatars from Crimea so its provocative agenda has eventually failed.

During the 23 years of Crimea’s stay in Ukraine, there was not a single law passed on the rehabilitation of previously deported Crimean Tatars or a single programme for their resettlement. Yet on 21 April 2014, just a month after the law was signed making Crimea part of Russia, President Vladimir Putin signed a decree on the rehabilitation of Crimean Tatars and other repressed minorities in the peninsular.

On 21 April 2019, exactly five years after the decree on the rehabilitation of the repressed peoples of Crimea, a cathedral mosque will be opened in Simferopol. Crimean Muslims have been waiting more than 17 years for it. Beneath the mosque will be a Museum of the Islamic Culture of Crimea, as well as classes where anyone who wants can study Islam. There are around one thousand mosques on the peninsula and they are often located next to Orthodox churches. And this is not a fake, but the new reality in which Crimean Tatars live today.

Project of the new grand mosque under construction in Simferopol

The Crimean Tatar language has been given official status alongside Russian and Ukrainian. The children of Crimean Tatars can now get education in national schools and classes. They know that their language is protected in Russia by its legal status.

According to data from Russia’s Federal Agency for Ethnic Affairs, three years after Crimea joined Russia, 65% of Crimean Tatars have a positive view of the situation in Crimea and around 70% have successfully integrated themselves into Russian life. Only 13% of those surveyed support Kiev’s policies. Even the Ukrainian human rights defenders recognise that the majority of the Crimean Tatars have no plans to move away from Crimea.

Meanwhile Ukraine and Western propaganda machine keeps creating myths and fake news about the Crimean Tatars in Russia. The state that used military force to annex Crimea in the 1990s, did not recognise any kind of official status for the language of the peninsula’s largest ethnic minority, and, following the Crimean referendum, closed the North Crimean Canal and allowed the destruction of power lines, depriving Crimeans (including hundreds and thousands of Crimean Tatars) of water and electricity, is now tirelessly thinking up ‘laws’ to support the Crimean Tatar people – with the proviso that Crimea be ‘returned’ to Ukraine.

The people of Crimea are sure that in February 2014 they made the right historical choice to be with Russia. Remzi Ilyasov, a former functionary of the Mejlis and currently vice-speaker of the State Council of Crimea, has expressed his willingness to convey «the voice of the Crimean Tatars» to the world from the UN rostrum. He talks convincingly about the fact that the peninsula’s reunification with Russia was based on the legitimate will of the Crimean people and any attempts to present the Crimean Tatars as opposed to this reunification are simple speculation and have absolutely nothing to do with reality. «Only the Crimean Tatars who live in Crimea have the right to decide about their future».